Period tracker apps and your privacy: How much info can companies or other parties access?

Nearly a third of women in the United States use a period-tracking app at some point in their lives, according to a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Tens of thousands are now scrambling to delete them over privacy concerns in the wake of the Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Apps that help monitor menstruation and fertility often contain heaps of personal data. Flo, Clue and Glow, among many others, help women know when to expect their periods, track fertility, manage birth control use – and potentially help with zeroing in on a myriad of other health-related concerns.

Every woman I know uses one, from teens trying to figure it all out to women starting menopause. So, what’s the risk?

Period-tracking apps and privacy concerns: We answer your questions

Are period trackers risky?

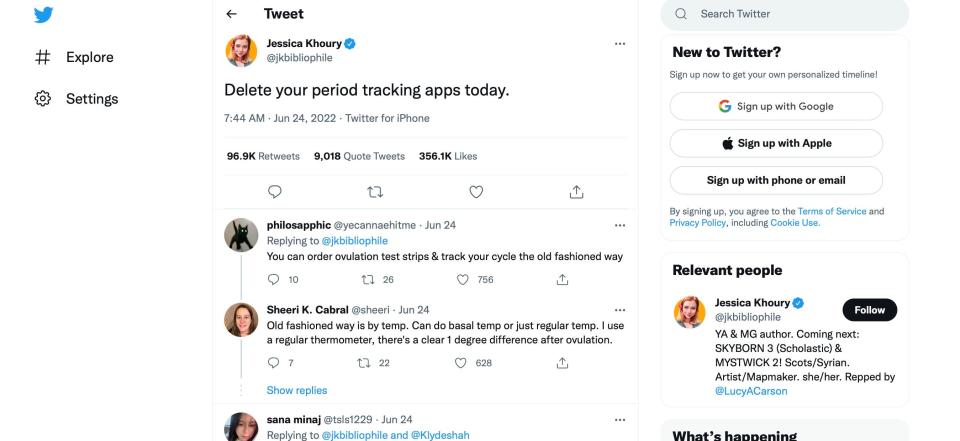

You may have seen the trending hashtags and advice to “delete your #periodtracker” pop up all over your social feeds lately. Privacy advocates say the biggest concern right now is that the sensitive data these apps collect could potentially be used against people in states where abortion may be criminalized.

But companies have been sharing and selling our personal data for years without warning us. Still, period-tracking apps obviously know a lot about people who use them – but how much information is accessible by the companies behind them – or by outside sources? More than you might think.

The makers of one of the top apps in this space, Flo Health Inc., settled with the Federal Trade Commission in 2021 over claims it shared sensitive health information with outside advertisers and analytics companies without proper disclosure.

Abortion bans and employer-based insurance: Are interstate travel bans next?

In 2020, another highly regarded app called Glow, which focusses on fertility, settled a suit with the state of California over “serious privacy and basic security failures that put women’s highly-sensitive personal and medical information at risk.”

Earlier this year Consumer Reports evaluated the privacy practices of eight different period trackers, only to find “lax privacy protections,” in nearly all of them.

To delete or not delete…

Is it time to #deleteyourperiodtracker? Not necessarily.

Deleting an app isn’t enough to clean up all your digital breadcrumbs – and texts, web searches and location history could be more incriminating than the information on a period-tracker.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) notes “abortion seekers face much more urgent threats right now and period tracking apps are not at the top of the list of immediate concerns.”

Among the most urgent of those threats, according to the EFF, is that most women who face charges around a terminated pregnancy usually get turned in by friends, family members and even hospital staff. That opens the door for investigators to then comb through someone’s messages and web activity, which has led to some of the strongest evidence to date in criminal cases around illegal feticide (the act of causing death to a fetus – typically used to protect pregnant women against abusive partners or nefarious abortion providers).

In 2015, an Indiana woman was sentenced to 20 years for charges including illegally causing her own abortion. Investigators based those charges largely around texts she sent a friend about ordering pregnancy-ending pills from a pharmacy in Hong Kong, taking the medication and then losing the pregnancy a few days later. The sentence was later overturned, but the woman still spent more than a year in prison.

Which companies are paying abortion travel costs? Dick's Sporting Goods, Google, Disney

There’s a similar case from 2017 in Missippi where a mother of three was charged with second-degree murder and held in jail for several weeks before charges were dropped. Her case also centered around text messages and web searches related to pills that cause abortion. One reproductive group reports at least 60 similar cases in America since 2000.

It’s also important to note here that health apps in general – except for data shared between you and your healthcare provider directly – usually do not fall under protection from HIPAA privacy rules.

Choosing the right app

Rather than give up digital tracking entirely, there are several ways to ensure the most privacy possible, starting with end-to-end encryption. Here are more details on exactly what to look for.

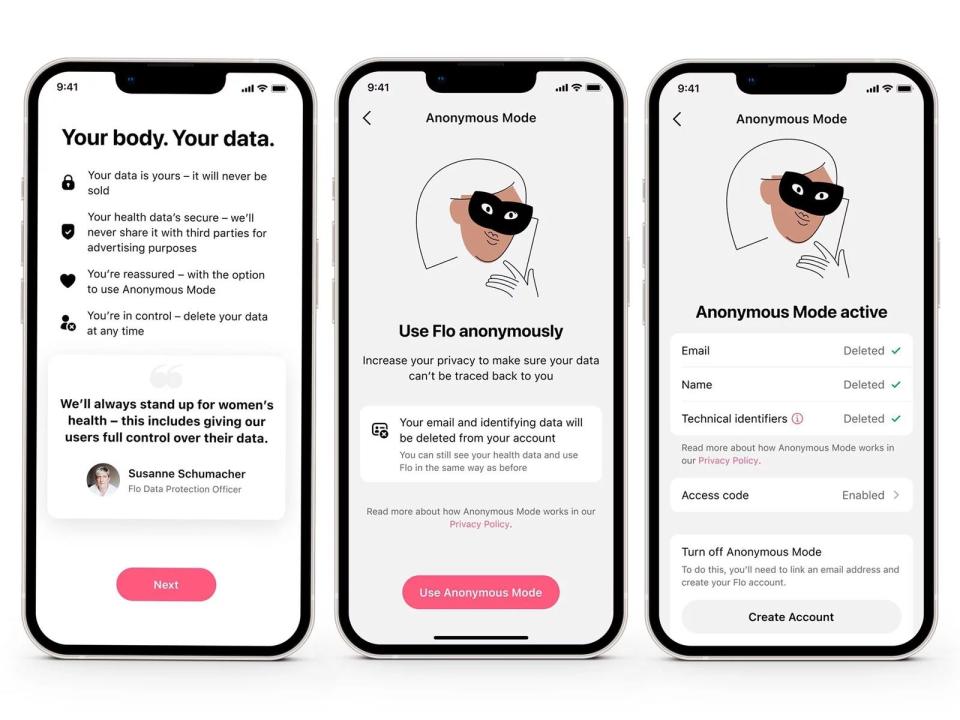

Encryption: Apps that encrypt data – and don’t link it to personally-identifiable information – are your best bet. Apple’s Health app, for example, features end-to-end encryption. Flo also recently launched an “Anonymous Mode” that lets you scrub your personal information from your account.

In a press release, Flo said this new feature “deidentifies data on a deeper level” by removing personal email, name and other technical identifiers. That means even if law enforcement subpoenaed Flo to identify someone by name or email, “Anonymous Mode will prevent Flo from being able to connect data to an individual, meaning Flo would not be able to satisfy the request.”

Location: A company’s location may dictate what data they can collect and/or share with law enforcement or other organizations. In a recent message by the co-CEOs of the Clue app, Carrie Walter and Audrey Tsang, explain that they don’t share data “for anyone’s use” and they “won’t disclose it.” They also note that the Berlin-based company is beholden to European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) laws, which gives users an additional layer of protection.

Selling data: Be weary of an app that “reserves the right to sell or market your data.” If an app maker sells your data to a third party and includes identifiable information, a data broker could get served with a legal request and law enforcement might be able to scrape your data anyway.

Roe reversal and your health insurance: Answering worker and employer questions

Wake up call for more digital privacy?

Whether dealing with something as politically and emotionally charged as abortion – or even trying to justify the web searches I’ve used to research this very story – it’s chilling to think of the narrative someone could create using digital breadcrumbs.

No matter what, it serves as a solid reminder for all of us to think more critically about how much of our sensitive information gets captured through our daily online activities. We also need to reconsider the steps we take – if any – to protect our data. Even something as simple as using a more private web browser such as DuckDuckGo might help keep personal and sensitive searches more private overall.

Jennifer Jolly is an Emmy Award-winning consumer tech columnist. Email her at jj@techish.com. Follow her on Twitter: @JenniferJolly. The views and opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of USA TODAY.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Period tracker apps: How much info do companies and third parties see?