Periods are a nightmare in Gaza's crowded, unsanitary camps. Women are using birth control to skip them

Crouched inside her makeshift tent at a camp in Rafah, Samah El-Nazli fidgets as she recalls what her living conditions have been like since the war began. The mother of four is among millions of Gazans struggling to access food, water and sanitation in the overcrowded camp after losing their own homes in the strip.

"There's no way to keep clean, there's no way to be comfortable — we're living a completely destroyed life," she said.

Many women and girls living in the strip have opted to start taking birth control as a way to stop their periods as the conflict nears its eighth month.

El-Nazli, 34, said she tried everything to manage her cycle — from adult diapers to dirty cloth — before seeking out medication to stop her period altogether.

"None of these things are good," she said in an interview while she reorganized the pots and pans lining the nylon walls of her tent.

Humanitarian groups and experts in reproductive health say the choice women in Gaza face shows how desperate conditions are in the besieged enclave and how the war is disproportionately affecting women and girls.

Over half a million menstruating in Gaza

El-Nazli was displaced early in the war from her home in Abraj el Mokhabarat, a town in northern Gaza. She sought refuge at Al-Aqsa hospital before making her way south with her family and pitching a tent in Rafah in October. She's currently living with her four daughters in the displacement camp.

Getting aid into the Gaza Strip has become an issue since Israel imposed a siege on the area following the Hamas-led attacks on Oct. 7, making supplies in shops and pharmacies limited and expensive.

Before the war, El-Nazli said, everyone had their own homes and spaces. Now, they have tents.

"It's where I pray, where I sit, where I bathe myself and my daughters," she said. "There's no cleanliness. There are no bathrooms in the place where we live."

WATCH | 'They started asking for the pills that will delay the menstrual cycle':

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), there are more than 690,000 menstruating women and adolescent girls in Gaza — all of whom are facing limited access to menstrual hygiene products and inadequate washroom facilities.

In a report published last month, UN Women said an estimated 10 million disposable menstrual pads or four million reusable sanitary pads are needed each month to meet the need in Gaza.

Laila Baker, regional director of UNFPA in the Arab States, said the living situation is a "nightmare" from the perspective of privacy for women and girls. She said the bathrooms in camps, schools and hospitals are overcrowded because the buildings — sometimes designed for no more than 400 people — now house thousands who've been displaced from their homes.

According to Baker, there are long lines for toilet facilities that are serving up to 1,000 people.

"Even if you could find water or soap, which are in short supply, it would be with the complete lack of privacy," she said.

"So some women and parents are resorting to desperate, desperate measures and giving birth control pills where they can get their hands on them."

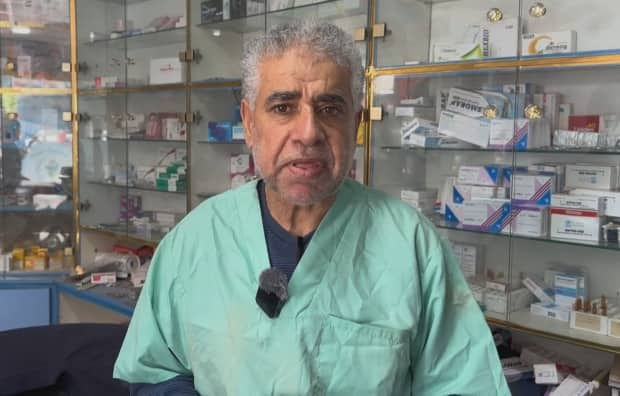

Women can access the pill through pharmacies or the health ministry, which can still provide the medication locally, says Rafah pharmacist Hatem Muslim.

The ministry gets the pills from abroad, he says, but there was little demand for it before the war. He noted that this created a large stockpile that's now being used to keep up with an increased demand.

"We realized that many women are taking birth control pills, or period delaying pills as they call them."

Dr. Jerilynn Prior, the scientific director of the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research at the University of British Columbia, says it's "terrifying" that women in Gaza are resorting to the pill not as a matter of choice, but as a matter of circumstance.

"The idea that women in the war zone in Gaza don't have adequate sanitary access is just awful," she said. "It's yet another of the tragedies of war that women tend to bear the brunt of it."

Women start their periods when their hormone levels drop roughly once a month as part of their menstrual cycle. Usually, those on hormonal birth control take a placebo pill during the week of their period.

Birth control can delay a period if women skip the placebo pills and continue taking hormonal pills instead. This prevents the dip in hormones and without that trigger, Prior explained, menstruation doesn't begin.

In Gaza, birth control pills are much cheaper and more readily available than pads or tampons. Muslim said a month's supply of birth control pills costs roughly 10 shekels, or $3.65 — less than half the current cost of a pack of pads.

WATCH | The struggle to get aid to Gazans in need:

Choosing between food and hygiene

For Fadwa Muhanna, 30, the decision to take birth control to delay her period meant having more money to feed her family.

"We face a lot of difficulties getting necessities like feminine hygiene products and if we find them, the prices are very high," Muhanna said in an interview from the displacement camp in Rafah.

"This isn't an easy amount to spend for a big family, so it's 'Do we get our needs or do we get sanitary napkins?' "

Muslim, the pharmacist, says he also sees mothers come in looking to start their daughters on birth control so they don't have to stand in line for hours to use bathroom facilities in the camps.

He says the girls are often embarrassed about the topic of menstruation in general and "the fact they can't maintain their personal hygiene."

Although women using birth control as a means of skipping their periods is not uncommon, Prior says it's not the most effective strategy because it can simply "change the scheduled bleeding to unscheduled spotting."

Although the pill is safe to use, Prior says women who use it long term to delay their periods are at a greater risk of blood clots compared to those who use it cyclically. She says the risk of blood clots in young women is generally low, but notes the risk increases on the pill.

She says there should be an alternative to the pill for women who don't have access to a regular supply of tampons and pads and don't need contraceptives.

"The menstrual cup would be a better way to improve sanitation for menstrual flow than continuous combined hormonal contraceptives," Prior said, referring to devices made of rubbery material that are inserted into the vagina to collect menstrual fluid. They can be emptied, washed and reused.

However, getting access to such devices in a warzone is difficult, if not impossible.

Baker says humanitarian aid groups need unfettered access to Gaza to deliver aid, including menstrual hygiene products.

"We need a complete and permanent humanitarian ceasefire," she said, so women don't have to choose between buying menstrual products for themselves and feeding their families.