Peter Bart: With Hollywood Stalled, New Book About Writer’s Angst Creating ‘Chinatown’ Climbs Bestseller Lists

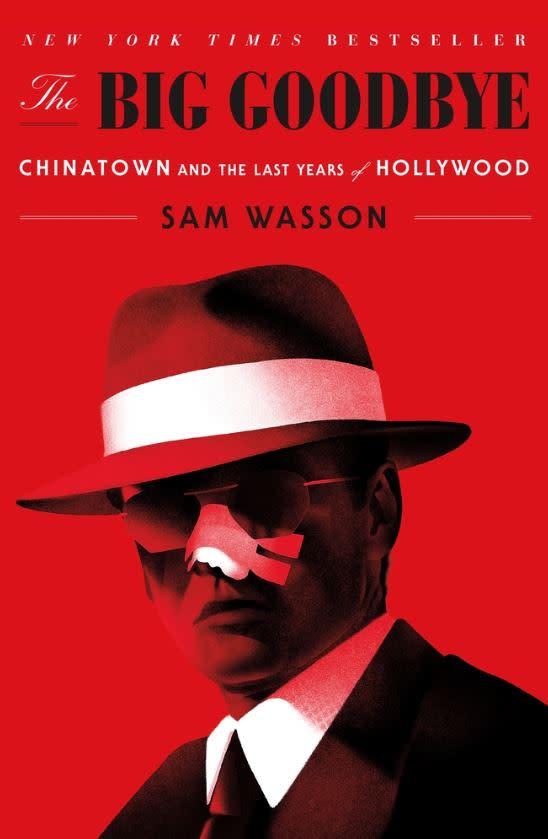

Theaters are shut, production postponed, dealmaking stalled and writers are twisting in the wind. Given these conditions, it’s perversely appropriate that the hottest new book about the movie business is focused on an angst-ridden writer. The Big Goodbye doesn’t try to make the writing trade seem like fun, but the creation of Chinatown is steeped in so much drama and pathos that Sam Wasson’s book has propelled itself onto bestseller lists.

More from Deadline

Peter Bart: 'Social Distancing' Will Also Expand Our Digital Dependency

2024 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Korean Film Council Taps Park Duk-ho As New Secretary-General

In writing his Chinatown script, Bob Towne’s agony was such that he became the only writer I can recall who actually hired his own ghost writer. And paid him. (Towne himself wrote almost all the script.)

The 1975 Jack Nicholson-Roman Polanski noir classic won 11 Oscar nominations, including Best Original Screenplay for Towne, but throughout the three-year writing process it seemed increasingly unlikely that the movie would ever get made.

Towne had earlier done touch-ups for The Godfather and other important films, but to move Chinatown into production he had to deal with a manic depressive director who periodically stopped talking to him, a studio chief whose career was on the brink of collapse, and a star who didn’t believe that the dialogue in screenplays really mattered in the total picture.

Deliberations grew so disruptive that at one point Towne, though broke, decided to pay another writer, Edward Taylor, to cope with the madness and contribute key scenes (Taylor, an old friend, never demanded credit).

At its inception, Chinatown seemed like a dream project. Nicholson, then a rising young star, had developed a friendship with Towne during production of Easy Rider, and now implored him to create a Raymond Chandler genre detective story for him. Towne confided that idea to Robert Evans, then production chief at Paramount, who was eager to expand his portfolio as a producer, with the added compensation.

While Evans coveted a Towne-Nicholson collaboration as his first solo production credit, there was a catch: He didn’t want to make a movie about either China or Chinatown. Towne patiently explained that Chinatown was only “a state of mind,” whose intricacies involved incest, murder and a scheme to steal a city’s water supply.

Unmoved, Evans instructed Towne to abandon Chinatown, offering instead a payday of $175,000 to adapt The Great Gatsby. Towne angrily pointed out that a screenplay based on the Gatsby novel would be even more confusing than Chinatown.

To prove his point, Towne turned his back on Paramount, and borrowed $10,000 to rent a bed-and-breakfast cabin on Catalina where he would start writing. While he relished his freedom, it proved illusory. There were still other voices with other opinions.

Over time he would find himself re-crafting his story with guidance from a succession of contributors with strong opinions. First came Nicholson, who had ideas about the characters but felt that the specifics of dialogue were not relevant. Next came the Polish-born Polanski, who confessed he was baffled by the subplots of Los Angeles politics. Finally there was Evans, who found the narrative impenetrable.

One recurring topic of disagreement: violence. Only two years earlier Polanski had experienced the murder of his pregnant wife Sharon Tate, and he now insisted that, in his new movie, the violence would be explicit, not implied. “If a filmmaker tries to avoid upsetting people, that would be immoral,” he argued. Even the physical fight between Nicholson, as Harry Gittes, and Faye Dunaway, as Evelyn Mulwray, would be graphic in its execution.

Once production was finished, further disagreements ensued. The ending was re-written, the original score abandoned. Nicholson felt the “look” of the film as a whole was “too bright.” When finally screened for critics doubts vanished. The reception was ecstatic, the movie declared an instant classic.

Flatiron Books

In chronicling Chinatown’s complicated history, Wasson had anticipated potential hazards. He had written four previous books which had been well received including a biography of Bob Fosse. Still, on Chinatown Nicholson sent word that, while he revered the movie, he would not cooperate with the research. Towne, always secretive about his work, also declined to discuss the movie.

A diligent researcher, Wasson contacted other insiders who had worked on the film. Polanski was helpful via phone interviews, and Evans, prior to his death, was a font of information. The upshot: A book that presents a vivid picture of a key moment in Hollywood history as well as the gripping odyssey of a writer struggling to convert his vision into great cinema. (Personal disclosure: While I was a Paramount executive at the time, I declined to participate in any way in Evans’ production and focused instead on the studio’s 20 other films).

“A screenwriter dreams his dream, then a director tells the writer, ‘We don’t need you anymore,’ ” writes Wasson. Remarkably, Towne survived, as did his vision. His fellow writers may gain encouragement from that fact.

Best of Deadline

Which Emily Henry Books Are Becoming Movies? ‘Happy Place,’ ‘Book Lovers,’ Among Others

The Making of Bond: Behind-the-Scenes Photos of Sean Connery from 'Dr. No'

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.