Port Moody council passes provincially mandated housing bylaws, but with significant qualms

Port Moody council has passed provincially mandated housing bylaws for Bills 44 and 47, but not without voicing serious reservations.

Both pieces of legislation forced municipalities to enact hefty new bylaws by June 30, 2024 which consequently shelved Port Moody’s long-awaited revision of its official community plan last March.

The “challenges, concerns, shortcomings” related to the two bills were detailed in a report to council on June 18.

Mayor Meghan Lahti said she struggles to see how the proposed changes will result in any relief related to the housing, affordability or climate crises.

She questioned whether the money the province spent developing this legislation would have been better spent directly on housing.

“I can’t see this righting the ship,” Lahti said. “I hope it does, but drawing arbitrary lines on a map just doesn’t seem to be the way that you plan a community.”

The top-down, inflexible nature of recent provincial legislation has been frequently criticized by locally elected representatives since it was announced in late 2023, as it broadly diminishes local government’s authority over how it plans for growth.

The report, which was compiled by a team of city staff and consultants, also did not shy away from criticism of the legislation.

Bill 44 is causing major changes to Port Moody’s zoning bylaw by mandating minimum allowances for small-scale multi-unit housing (SSMUH) on single-family lots.

It effectively means that every single-family zoned lot in the city will be able to house a minimum of three units, up to a maximum of six units if within 400 metres of a prescribed bus stop.

The only lots exempt are those falling under heritage protections, areas unconnected to water and sewer infrastructure, or within a transit oriented area (TOA) designation.

An analysis from staff showed that only nine parcels in the entire city (outside of TOAs) had exemptions. In total: 12 lots qualified for three units, 3,709 lots qualified for four units, and 515 lots would be allowed up to six units.

Staff described the SSMUH legislation as a non-consultative “broad-brush” approach that can be “illogical and confusing.”

They added the extremely tight turnaround time to adopt the bylaw meant there has been little time for proper analysis and consultation, likely leading to oversights, inaccuracies and the need for future corrections.

While meetings hosted by the provincial government have led to some clarity, staff said questions abound related to infrastructure upgrades, parking impacts, unit sizes, lot coverage, tree canopy targets, and control over form and character.

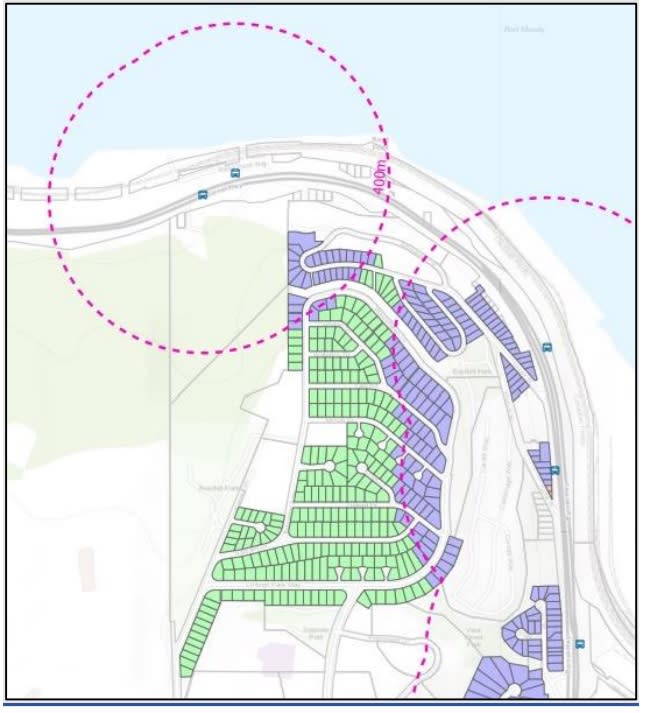

Some lots that will be permitted six units have no direct pedestrian access to their correlating bus stops, while many other blocks will have varied density allowances simply based on whether they are captured under the 400-metre radius.

A map was used as an example to show how the province’s “arbitrary” circles come with specific challenges in Port Moody.

“Changing zoning regulations mid-block is not good planning and presents a number of urban design and servicing challenges,” the report said. “There are blocks that are partially within the 400m ring where six units are permitted, and the rest of the block is within a TOA area where up to 20 storeys.”

Staff added there was no flexibility on this topic during discussions with the province.

There are also questions as to how much the city can control when issuing development permits.

Staff said that because SSMUH is a form of multi-family housing, they believe these developments should be subject to form and character requirements to prevent the proliferation of “cookie cutter” designs.

However, Coun. Diana Dilworth cautioned that the province has recently hired consultants to create stock designs for SSMUH developments. “I think we may not be able to avoid some of that,” she said.

Another “unintended consequence” of the new bylaw, according to the report, is that it may diminish developers’ incentives to seek land assemblies and go through the rezoning process for medium-density projects.

Port Moody’s OCP envisions townhomes and low-rise apartments in certain areas of the city, but time, cost, and complexity considerations may lead developers and landowners to opt for SSMUH developments.

Jim McIntyre, an independent consultant, said the new OCP will have to be updated with design guidelines and policies to encourage these types of housing forms.

“That’s a big question. You can’t tell property owners to assemble their lots, you can encourage them, but you can’t force them,” McIntyre said. “It gets challenging, frankly; six units on a 60 foot-wide lot, how does that all fit?”

Tree preservation is another issue, which is usually negotiated through rezoning. However, the provincial guidelines state that municipalities cannot use the development permit process to restrict landowners from achieving their maximum permitted density.

Port Moody’s bylaw instead pivots to requiring tree replanting to achieve adequate canopy coverage over time.

“They are really cautioning local governments from putting any sort of restraints or obstacles that inhibit a property owner from achieving that entitled density,” McIntyre said.

Port Moody has already submitted resolutions to the Lower Mainland Local Government Association and Union of B.C. Municipalities, requesting the province to incorporate tree protection into its housing legislation.

Coun. Amy Lubik, who introduced that resolution, said Bill 47 leaves the city little “wiggle room.”

She said the region is in an ecological crisis as well as a housing crisis, and protecting tree canopies can save lives.

“It’s not just nice to have, we know that the neighborhoods during the heat dome that had greenery and tree canopy were the ones that were less likely to lose people,” Lubik said.

Bill 47, on the other hand, mandates that municipalities establish TOAs around rapid transit stations, requiring minimum density allowances for developments within certain distances.

Land captured (or partially captured) in a 200-metre radius of a skytrain station must allow projects up to 20 storeys; lots within 400 metres must allow 12-storey projects; and lots within 800 metres must allow eight-storey projects.

Staff said both provincial housing bills provided very little consideration for pressures on the city’s infrastructure, including exemptions for safety concerns and extensions related to capacity.

Port Moody’s water distribution, sanitary, and drainage systems, as well as the transportation network will all be impacted, according to staff.

“Will provincial government funding be made available to help cover the capital infrastructure project costs necessary to support this growth?” the report asked.

Coun. Callan Morrison said Port Moody’s unique geography means it will be the most heavily affected municipality, simply due to the overall land percentage captured under the regulations.

He added that while the legislation claims to want to create complete communities, it does not address tree canopies, job creation, affordable housing minimums, nor how to pay for significant infrastructure upgrades or amenities.

Even if the city wants to purchase a park to service growth for these areas, Morrison said they will have to buy it at highly inflated prices due to land speculation.

“Painting every municipality with the same brush is the completely wrong way to approach the housing issue in B.C.,” Morrison said. “I intend to keep a very close eye on this process and the unintended consequences of this provincially-rushed legislation rollout.”

Coun. Haven Lurbiecki noted that industrial-zoned lands are exempt from being captured by TOA, and the city needs to protect large areas along S. Johns, Murray and Spring streets in order to expand its industrial tax base.

She said density envisioned in Port Moody’s new OCP draft needs to be reconsidered, otherwise the city’s infrastructure and services will be overwhelmed by “catastrophic overdevelopment.”

“The (provincial) legislation is dramatic, and the response needs to be,” Lurbiecki said. “I think we have to go back and look at everything.”

While Dilworth acknowledged staff’s concerns about Bill 47, she said the number of homeowners that will apply to have SSMUH development on their properties will be low.

The City of Vancouver rolled out their multiplex program last fall, yet received only 19 applications in the first couple months, according to Dilworth.

“We need to tamper down any fear that these are going to be popping up on every block and every corner lot in Port Moody,” Dilworth said. “There are huge financial barriers for people to develop SSMUH on their properties.

“Once (property owners) get down into the nitty gritty, the financing just won’t work out.”

Coun. Kyla Knowles agreed, stating the SSMUH legislation is an opportunity to “densify gently” in areas outside of TOAs.

“Having this option and guideline is important, as we look towards increasing housing stocks across Metro Vancouver,” Knowles said. “We have to have sensible policies across the city. So this is much needed.”

The city will be submitting a cover letter to the province outlining all of its concerns with the two bills.

Patrick Penner, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Tri-Cities Dispatch