Racism against aboriginal people in health-care system 'pervasive': study

Michelle Labrecque pushes herself gingerly in a wheelchair down the hallway of a hotel. The Oneida woman was recently found to have a fractured pelvis, but she says it took three trips to the hospital and increasing pain before she received that diagnosis.

"The third time, I was just left in the ER room, not being able to walk anywhere. Nobody around to help me, not even to a wheelchair," says Labrecque.

She felt abandoned, she says, because she’s native.

It wasn't her first bad experience at Victoria’s Royal Jubilee Hospital. In 2008, she sought medication for what she describes as severe stomach pain. She discussed the pain with a doctor, as well as her struggles with alcohol and finding a home.

- First Nations, Second-Class Care

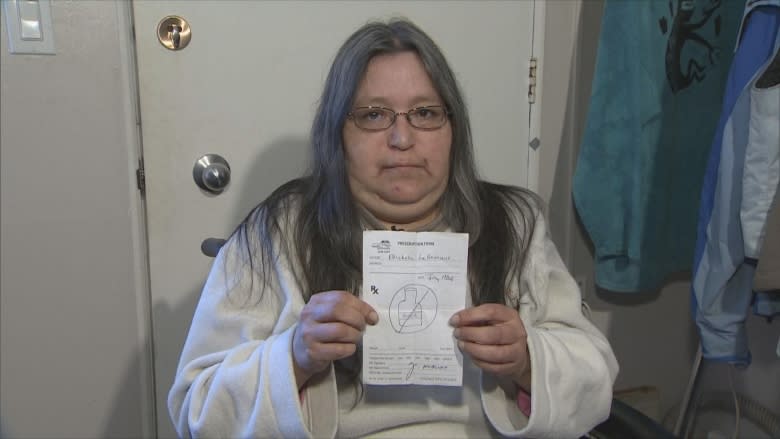

The doctor wrote her a prescription, and told her she was good to go. When she got home, she discovered all the doctor had scribbled on the prescription form was a crude drawing of a beer bottle, circled with a slash through it.

"It just blew my mind, what they put on it. It's discriminating against natives, I'm pretty sure," says Labrecque. She complained to the hospital, who told her the doctor was disciplined, though she never found out what happened to him.

'Unconscious, pro-white bias'

A new study suggests racism against aboriginal people in the health-care system is "pervasive" and a major factor in substandard health among native people in Canada.

The study — called First Peoples, Second Class Treatment — was released today by the Wellesley Institute, which researches public health issues.

"It bothers me that people think it's OK to pretend we don't have these issues in our own backyard," says Dr. Janet Smylie, a Métis doctor and lead author of the study.

The study says well-documented disparities in aboriginal and non-aboriginal health are rooted in colonial government policies, such as segregation and Indian residential schools.

But Smylie says negative stereotypes about aboriginal people and an "unconscious, pro-white bias" among health-care workers continue to harm aboriginal health.

"Within the health-care context, unfortunately, the kind of unintentional implicit associations which lead to differential treatment are alive and well."

The study suggests aboriginal people experience racism from health-care workers so frequently that they often strategize on how to deal with it before visiting emergency departments, or avoid care altogether.

Avoidance strategies based on racism

That was the case for Carol McFadden. The 53-year old Oneida woman, living in Victoria, admits she's wary of the health-care system after witnessing her brother experience discrimination from doctors and nurses when he was ill.

"When you're sick, you're at your most vulnerable. You need somebody there to help you stave off those horrible comments, those horrible looks," says McFadden.

A few years back, a lump in her breast that was long ago diagnosed as a plugged milk duct started to feel unusual. When she visited a clinic, she says, the doctor told her she could check out mammography on her own, and needn’t have come in.

This fall, McFadden returned to a hospital, to learn she had stage 4 breast cancer. She's now undergoing chemotherapy, but the cancer has spread to her liver.

Some doctors have been compassionate, she says, but others have been rude — kicking her bed when they want her attention, or asking if she drinks or does drugs. She hasn’t had any alcohol for two decades.

"You go to a clinic, and they don’t treat you as a human being. You're somebody that's wasting their valuable time, that they could be spending on somebody more deserving of the health-care system," says McFadden.

"If I'm somebody with white skin — if I'm somebody that looks like their relative, their auntie, their grandmother — I don't believe they would treat me that way."

Indigenous health solutions

In the study, Smylie recommends several solutions for dealing with racism in the health-care system, including more aboriginal health-care workers and "cultural safety" training for non-aboriginal health-care workers.

She also recommends aboriginal-specific health treatment programs.

Staff at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver say the recently created "Sacred Space" room has made a huge difference for aboriginal patients, by incorporating traditional healing into what many feel is a daunting hospital setting.

"Having this room here says ‘We welcome you, we welcome your family, we welcome your journey to healing and we’re here to help you in any way possible,’" says Carol Kellman, the aboriginal nurse practice leader at St. Paul’s.

Patients and staff join together weekly for talking circles, and traditional healers are welcomed to conduct aboriginal ceremonies.

James Raven, a 44-year old Cree man who is HIV positive, says the Sacred Space room transformed his healing journey. He visits the hospital at least once a week to get treatment for hepatitis C — treatment that now includes traditional aboriginal medicine.

"This space saved my life," says Raven. He points appreciatively at the healers who sit beside him in the circle. "I feel if it wasn’t for Creator and these people here today, I would be pushing up daisies. And that’s a fact."