Rappers like Takeoff are being killed. It's about more than their music

During a news conference on Wednesday morning, Houston police chief Troy Finner had few updates about rapper Takeoff's death the night before in a downtown bowling alley. But after confirming the rapper's identity (Kirshnik Khari Ball) and the fact a suspect had not been arrested, he did have something to say.

Speaking to a crowd of reporters in the room and the millions of fans Takeoff and his group Migos had amassed, Finner cautioned the public about demonizing the hip-hop community following the loss of one of the genre's most famous names in the last decade.

"Sometimes the hip-hop community gets a bad name, and I know … a lot of great people in our hip-hop community and I respect them," he said.

"We all need to stand together and make sure nobody tears down that industry."

The choice to stress that point is tied up in the perception of hip-hop and an ongoing issue that seems to perpetually dog the genre — the premature deaths of some of its most promising artists.

But as Finner also stressed, there was no indication Takeoff himself was at all involved in criminal activity and was more than likely just an innocent bystander caught by violence swirling around him.

Alongside that, a fraught debate has emerged about the cost of authenticity in the hip-hop community, where artists might feel pressure to live up to the lifestyle they describe in their music. Others say the genre is unfairly scapegoated and that violent lyrics don't translate into real-world violence.

Successful rap artists aren't insulated from violence

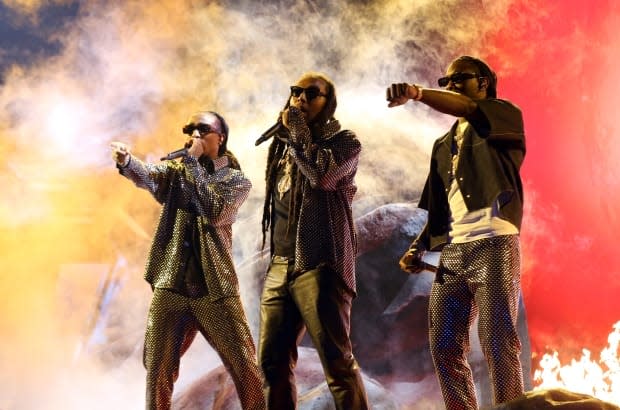

After news broke of Takeoff's death on Tuesday, the music community mourned the 28-year-old artist who, as a member of the rap trio Migos, pioneered a new sound in rap and hip hop.

But while fans expressed sorrow at Takeoff's passing, the level of surprise is unique to the world of hip hop. While the death of celebrities at the top of other genres, like Drake or Taylor Swift, would be extraordinarily unexpected, this year seven rappers have been killed — giving fans a rubric of how to react when one of biggest hip-hop stars is killed.

Migos' impact on hip hop and culture at large is impossible to ignore, and far exceeded expectations from their beginnings.

"They're like the Beatles for the rap [world]," Toronto rapper Pressa told CBC News, referencing how they influenced both the music industry and pop culture.

Though Versace didn't make it high on the charts when it was released in 2013 — peaking at 99 on Billboard's Hot 100 — it proliferated in Atlanta clubs and eventually reached international fame when Drake added an additional verse.

All the while, frontman Quavo and Offset — one half of a power couple with fellow musician Cardi B — drew most of the audience's attention; the quieter and youngest member, Takeoff, meanwhile seemed to take a backseat in interviews and performances.

But in reality, he was the one who largely drove their creative process — and whose mastery of their triplet flow initially drew the attention of Kevin (Coach K) Lee and Pierre (P) Thomas, co-founders of Migos' management company and label Quality Control.

"The Migos is their own thing," said Pressa. "You know, they had their own culture. They had their own sound. And I feel like a lot of people take their sound and kind of incorporate it."

WATCH | Takeoff's death prompts concerns about gun violence:

The fact that it was the more reserved Takeoff that was killed seemed to underscore the danger that some hip-hop artists face, even if their lifestyle is free from violence. But the perception of the group has previously parted ways with its nature — going back to the beginning of their careers, the men behind Migos were often plagued by criticism for a seeming dishonesty in their music.

As music journalist and poet Hanif Abdurraqib wrote in a 2017 piece for the National Post, some fans took issue with the fact that the three members, who grew up in a suburban area outside of Atlanta, would rap about drugs and crime.

That sentiment, Abdurraqib argued, pushed them to engage in behaviour more in line with their music, such as when Offset was arrested in 2015 — then attacked a fellow inmate in custody.

"Like Johnny Cash in the middle of the '60s, they spent time getting too close to the fire," he wrote. "It is hard to build a myth so large without eventually becoming part of it."

And in hip hop — a genre that puts a premium on authenticity and self-documentation in a way few other art forms do — they are far from the only group to be touched by violence. Since 2018, more than a dozen high-profile rap artists have been shot and killed.

Among them are Los Angeles rapper Nipsey Hussle, who was shot outside of his clothing store in 2019 — though he was most known for his community-building, general kindness and poetic, heartfelt lyrics. A year later, Toronto rapper Houdini was killed while shopping; Memphis-based Young Dolph was killed while buying cookies in 2021; and PnB Rock (real name Rakim Hasheem Allen) was murdered this year while eating lunch with his girlfriend at a small Los Angeles restaurant, in an unprovoked robbery after a stranger apparently saw his location in a social media post the rapper made.

After praising Allen as being a pleasure to work with, rapper Nicki Minaj implored other artists in the genre to stop making themselves so available to their community.

"You're not loved like you think you are," she wrote. "You're prey! In a world full of predators! What's not clicking?"

"It's just dangerous as an artist out there," Pressa agreed, who said he was with Migos member Offset at a separate event the night the shooting took place. "I don't like broadcasting and telling [my followers] where I'm going, and that's just what it is."

'It just didn't happen overnight'

But discussions around the causes of these incidents aren't simple. A.R. Shaw, an Atlanta-based trap music historian who wrote a book called Trap History, told CBC News that gun violence "trickles down" to communities of colour — because it's a broader issue in the rest of North America.

"I want to kind of get that notion out there that it just didn't happen overnight; that these are years of neglected communities and abuse that has occurred in communities of colour, particularly, and this is the repercussions of that," said Shaw.

"We've seen this pervasive violence that's occurring [among] artists and within the hip-hop community," Shaw added. "But it's also indicative of what's happening in communities nationwide."

Gun violence has generally been on the rise in Canada and the United States. Between 2018 and 2019, the criminal use of firearms increased by 21 per cent in this country, according to Statistics Canada.

Shaw said that the issue of gun violence began many years before rap and hip hop emerged as cultural forces. Where some would see violent messaging in some rap and hip-hop sub-genres as further fuelling violent behaviour, Shaw said it is often a documentation of — and a way of working through — the effects of long-standing trauma in those communities.

Rapping about crime and violence isn't causing the problem, he said, it's identifying it. "Hopefully we can change the narrative but we have to understand what the source is first."

On the other hand, some in the hip-hop world do see it differently. Kiana (Rookz) Eastmond, a Toronto music executive and former rapper, said that while rap has evolved as an outlet to deal with that trauma, as a genre it also pushes its artists to perennially focus on hardship. Other genres allow artists speaking about their lives to move on.

"We'd want to see them, you know, grow and evolve into a space where they don't have to share their trauma or [where] they're not defined by it. We don't ask for that from rappers," she said. "We don't ask them to ever find peace. We don't ask them to ever move on."

Likening it to the NFL, which for years ignored the damage concussions do before eventually bowing to public pressure and altering the game to protect athletes, she said the same thing should happen for hip hop.

Instead of demanding that rappers spend their careers mining the most traumatic moments in their lives — and then rewarding them for it — both the industry and fans should set a higher standard and demand music that demonstrates growth in the genre.

"Artists are people. And I think that in the same way that we expect our stories to be humanized in Black culture everywhere else, we need to expect that from hip hop now," she said. "We need to expect it from rap."