Rocky Mountain derailments leave train engineer unsure whether to change his career

From his living room in Cochrane, Alta., Mark Bretherton gets nervous when a train passes the tracks about a block away from his house.

Bretherton, who spent decades as a locomotive engineer, says working on those trains hasn't left him with much confidence about their safety.

"There's an old saying on the railway, 'Uphill slow, downhill fast, profit first and safety last," said Bretherton. "It's a known problem that's been going back for decades [and] things are not improving."

Five years ago this month, Bretherton was lead engineer on a roughly-14,000 ton, 10,000 foot Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) train carrying a variety of merchandise — including 12 cars of diesel fuel and one of hazardous waste — through the Rocky Mountains.

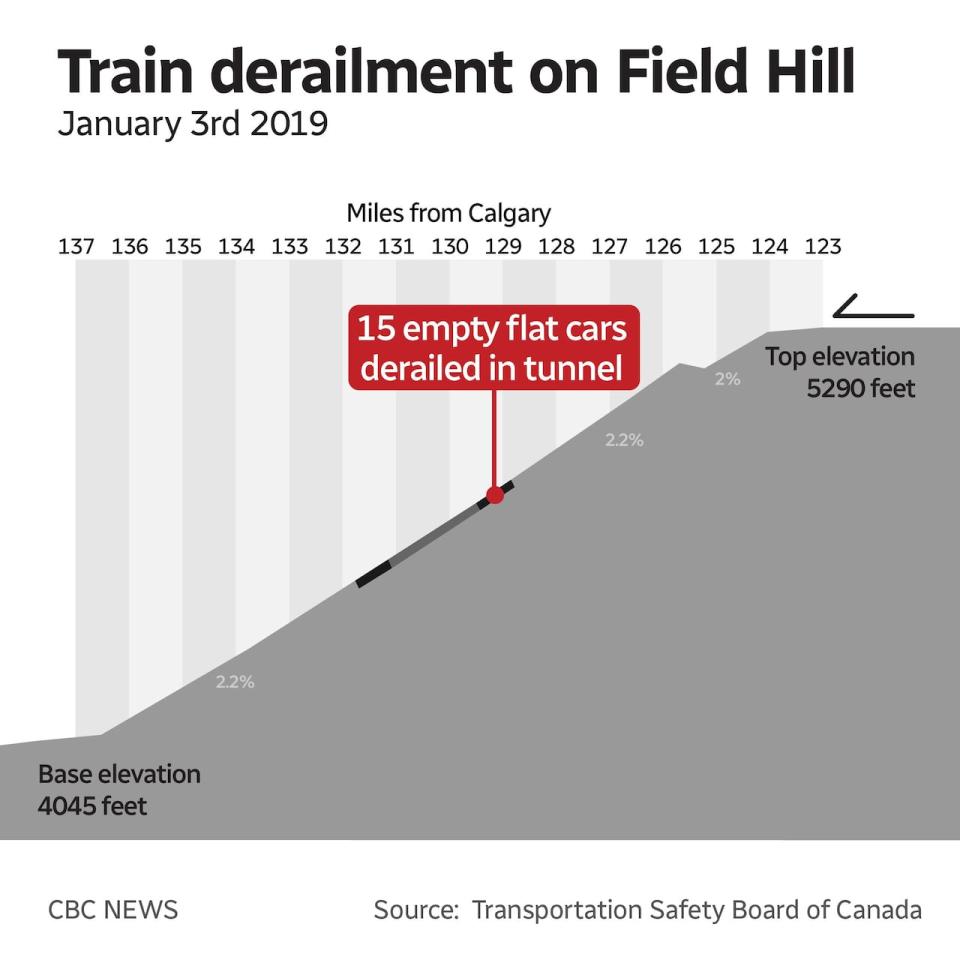

The train ran into repeated brake problems while descending Field Hill, a 13.5-mile section of steep track with several sharp curves, near the border between Alberta and B.C.

When the brakes first started acting up, Bretherton warned his rail traffic controller the problem would likely continue if they pushed on, but wasn't given a choice.

The train ultimately derailed after Bretherton finished his shift and a replacement crew took over.

While no one was hurt, Bretherton says he's bothered by the incident in part because of what came after. His derailment happened roughly a month before another derailment on Field Hill killed three crew members.

Bretherton, who said he's been on leave from the company due to stress since 2021, sees his incident as part of a broader problem: a culture that prioritizes speed over safety and where workers' concerns aren't taken seriously.

The problem isn't confined to CPKC or even to Canada, says Fritz Edler, a Washington-based special representative with the advocacy group Railroad Workers United. He said working conditions and workplace safety have worsened over the years, to the extent that many workers are trying to leave the business entirely.

"More and more of the people I know, they're just like, 'I can't wait till I get out of here … I just need to not be the guy who's on the train when the bad thing happens,'" said Edler.

CPKC, for its part, defends its record. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson said safety is "foundational" to everything it does, and that in the wake of the January 2019 derailment it took a number of steps to improve safety.

The company also said it's had the best track record of all Class 1 railroads when it comes to Federal Railroad Administration-reportable train accident frequency for over 17 years running.

Industry-wide, the Railway Association of Canada says its members have spent nearly 25 cents out of every dollar in the last decade on initiatives to improve the "safety, fluidity and resiliency" of the country's rail network.

Brake problems started during steep descent

Bretherton's account, along with a Transportation Safety Board (TSB) report released last year, paint a detailed picture of how a cluster of problems led the train to derail while on one of the most difficult sections of railway operating terrain in North America.

As the crew brought the train over the Great Divide, it started having brake problems, Bretherton said.

He applied a brake to control the train's speed as it started down Field Hill. He soon noticed on his control dashboard that air was flowing in the brake pipes, a sign that something was wrong and that the brakes were being released.

Bretherton stopped the train and told his rail traffic controller the brakes had released on their own, a problem he believed would likely repeat as the train continued down steeper terrain.

"I explained to him that I didn't think this train was safe to go down Field Hill and that it needed to be broken up into pieces and taken down in sections," said Bretherton.

(CBC News)

Bretherton also flagged the problem to the trainmaster, but wasn't given another option.

Once the brakes had recharged, the crew started up again, but soon ran into more problems. This time, a knuckle between two cars broke, setting off the emergency brakes and bringing the train to another stop.

By the time the knuckle was replaced, Bretherton and his colleagues had reached the end of their shift and were replaced by another crew.

"They arrived on the scene and I begged them not to take the train, I explained to him what the problems were, I said 'Please don't take this down the hill,'" he said.

When the replacement crew started down the hill for the third time, the train experienced yet another "undesired" brake release, according to the TSB report, forcing the replacement engineer to bring the train to a stop.

This time, the train's quick deceleration triggered a domino effect. Heavy cars at the back of the train pushed into empty cars in front of them, forcing one car off the tracks.

That, in turn, caused air hoses between two cars to separate, setting off the train's emergency brakes again and causing more cars to derail.

All in all, 15 rail cars derailed. No one was injured.

'Unconventional' tie wraps, marshaling were factors

The derailment was caused in part by problems with the train's equipment, and the way it was put together, according to the report.

The "undesired brake release" that set the derailment in motion was likely caused by problems with the equipment that links the train's rail cars and brake pipes together, according to the TSB report.

In this case, some of the train's gladhand couplings — the connectors that link air hoses between different cars — had been wrapped together with tie wraps.

This is supposed to keep the hoses from separating, but is also an "unconventional" practice that can cause the couplings to kink and increase the risk of brake pipes leaking or experiencing pressure fluctuations, according to the TSB report.

An employee boards a Canadian Pacific Railway locomotive at a railyard in Calgary. (Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press)

The report also drew attention to the way the train was put together, or "marshaled."

The risk of a train derailment goes up when light cars are placed in front of or in between heavier ones, according to the TSB.

In this case, the train had a group of loaded heavy cars at the front of the train, 71 empty cars in the middle and another 19 fully loaded cars at the end.

It was making several stops en route to Port Coquitlam, B.C., and was subject to "destination blocking," a strategy where trains are grouped together based on where they're headed, rather than strictly by weight.

"Under [destination blocking], train dynamics are affected and may not be optimal," the report noted.

Another derailment

Bretherton said he's particularly unnerved by the derailment because it happened almost exactly a month to the day and in roughly the same location as another derailment that killed three crew members: Andy Dockrell, Dylan Paradis and Daniel Waldenberger-Bulmer.

There were a number of differences between those derailments.

The train types were different and they were carrying different types of cargo, for example, and the extreme weather conditions and insufficient training that the TSB found factored into the February incident weren't cited as problems the month prior. (CPKC has disputed TSB's finding that training and inexperience factored into the February derailment.)

Still, both cases involved some element of workers raising concerns ahead of a derailment.

As the brakes on Bretherton's train started to malfunction, he flagged to both his rail traffic controller and trainmaster that the problem would likely continue. Still, "no alternative plan of action was considered," as per the TSB report.

In the case of the derailment that happened the following month, the TSB investigation that resulted noted that workers had raised concerns for years about grain unit trains having brake problems on Field Hill during cold winter weather, but there was never any formal risk assessment done and "insufficient corrective action was taken."

"Train crews are supposed to identify hazards," said Ian Naish, a rail safety consultant and a former director of rail investigations for the TSB.

"My impression from [the January 2019] report and from the other Field Hill runaway report which happened around the same time, unfortunately, I don't think people are really taking the reported risk very seriously and taking positive action to address the risks," said Naish.

Preventing accidents becomes even more important, he said, as trains become longer and heavier. The average length and weight of a mixed merchandise train today has more than doubled since the late 1990s, according to a 2020 TSB memo.

CPKC improving safety, says company

In response to a request for comment about Bretherton's derailment, a CPKC spokesperson said the company has taken a number of steps since, such as updating its marshaling restrictions and reviewing the makeup of hundreds of trains operating west of Calgary.

After the following month's fatal derailment, the railway revisited its train-handling procedures, introducing new cold-weather speed restrictions for Field Hill and developing an advanced training program for locomotive engineers operating in adverse conditions.

Naish says there hasn't been a similar derailment on Field Hill since, but warns the company needs to be vigilant.

"If you get complacent then you start adjusting things here and there and maybe modifying your instructions and then things could go wrong again," said Naish.

Edler, with the railway workers' advocacy group, believes railway companies won't make changes until they're forced, and says a more fundamental shift is needed.

As for Bretherton, he's still on leave and is mulling whether to return to the industry at all.

"I'm prepared to go back to work but conditions would have to change before I could do that in clear conscience," he said.

"My situation is impossible — I don't know what the future holds."