Sask.'s Lake Diefenbaker irrigation project was announced 3 years ago. Where is it now?

Almost three years after a major Saskatchewan irrigation project was announced, the head of a group representing rural municipalities says the provincial government should "get on" with it — while an organization that represents First Nations says the province should have consulted with those communities more.

But where is the Lake Diefenbaker project now?

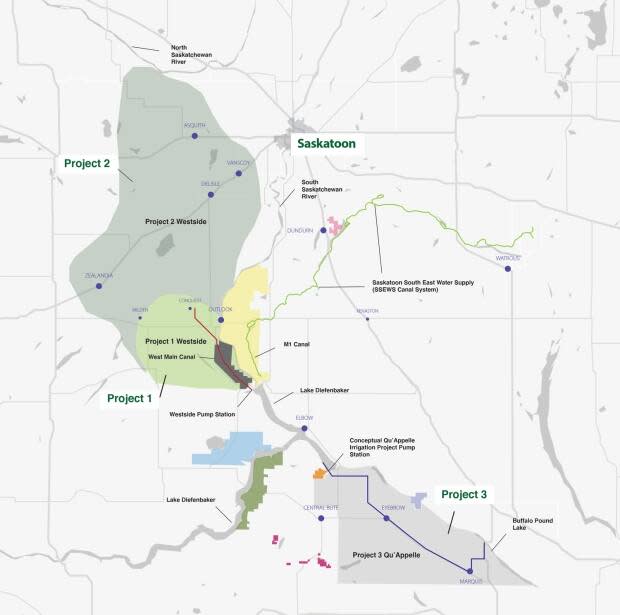

The $4-billion, three-stage irrigation project was announced in July 2020, with a plan to eventually irrigate some 202,000 hectares of land in southwestern and west central Saskatchewan with water from Lake Diefenbaker — doubling the amount of irrigable land in the province.

Saskatchewan reported that in 2019 that irrigation accounted for 50 per cent of the water used in the province.

The provincial government also said the project, which was originally forecast to be completed in about 10 years, would provide "building blocks for regional economic development in Saskatchewan," increasing gross domestic product between $40 to $80 billion over the next 50 years.

At the time, the legislative secretary to the minister for the Water Security Agency said the project would support diversifying crops.

He also said negotiations with First Nations would "begin immediately or almost immediately."

Patrick Boyle, a spokesperson with the Water Security Agency — the provincial Crown corporation responsible for water management in Saskatchewan — says the project remains in the preliminary investigation stage.

It has collected about 7,200 square kilometres of mapping data that examines the depth of water and topography and evaluated about 40,000 acres (just over 16,000 hectares) of soil, said Boyle.

"We're talking about hundreds of kilometres of canals that would run through this, so there's a lot of work and technical data that has to be collected to understand those better," he told CBC Radio's Blue Sky host Garth Materie.

The project is in preparation for environmental assessments and baseline studies for an assessment proposal are ongoing, said Boyle.

When asked if the project is on schedule, Boyle said it requires more information and more engagement to move forward.

"That's looking more … [at] that construction timeline. So we gotta get to that point, and we're working towards that goal right now," he said, adding that a current cost approximation also needs more information.

LISTEN | What is the status of Saskatchewan's mega-irrigation project?

The president of the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities said while he's in favour of the project, he wants the province to quicken its pace.

"We're just getting a little impatient," said Ray Orb.

"We're a little concerned of cost overrun now … and so that's why we're prodding the government — let's get on with this."

Orb said he's hoping the project will help diversify crop production and combat drought, which have dried up yields in recent years.

'We need new tools, not bigger old tools'

Murray Hidlebaugh, a farmer south of Saskatoon who uses irrigation, said he's been skeptical of the project since it was first announced.

He questions whether the cost of the project outweighs its benefits and is doubtful the province will conduct an environmental impact assessment.

"As a farmer, I'm pretty leery of really great, new, big ideas. I find they always cost me money and aren't a lot of benefit," he said.

"I also find that the large-scale irrigation projects are a problem from the standpoint that they have a significant negative impact both on wetlands and biodiversity, and in most of our farming areas this is a concern."

He said he has experience with tree farming and irrigation, and does not believe the project will provide the drought-proofing and diversification benefits the province intends.

The money could be better spent on initiatives like the food loop from Osler and Corman Park, near Saskatoon, Hidlebaugh said.

It would only take a few thousand acres to provide food for all of Saskatchewan, he said, but government policies support commodity exports over local food production.

"I'm supportive of the provincial government moving slowly and I applaud them, but I think we should use the time and money to look at alternative actions," said Hidlebaugh.

"We need new tools, not bigger old tools."

John Pomeroy, Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and the director for the Centre for Hydrology at the University of Saskatchewan, said the South Saskatchewan River has enough sources of water, largely from mountain snow runoff, to power an irrigation project.

When asked if reviving wetlands in the province would be a better option, he said it's not a question of which is better — but thinks both could help supply water to crops.

He also said soil salinity is better understood now than it was decades ago, and the areas susceptible to be overrun by salt would need to be assessed for whether they can be irrigated.

Environmental concerns: FSIN

Heather Bear, a vice-chief with the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, said First Nations weren't consulted about the Lake Diefenbaker irrigation project when it was announced.

Those communities are concerned about environmental impacts, and especially about water quality and water quantity, she said.

"This province should be concerned about the Saskatchewan River delta, the Cumberland House delta, and what those cumulative impacts have on the migration of millions of birds that come to this region from all over North America," she said.

The Water Security Agency's Boyle said in an email that "First Nations and Métis engagement is a priority. The project is at an early stage of engagement" and has had 567 separate "communications" with Indigenous communities, he said.

But Bear said she doesn't believe any First Nation owned and operated farms will benefit from the project, even though First Nation communities will be among the most affected.

"There needs to be, truly, a reset on this whole project."