Schools should stay open even if there's a 3rd wave of COVID-19, experts say

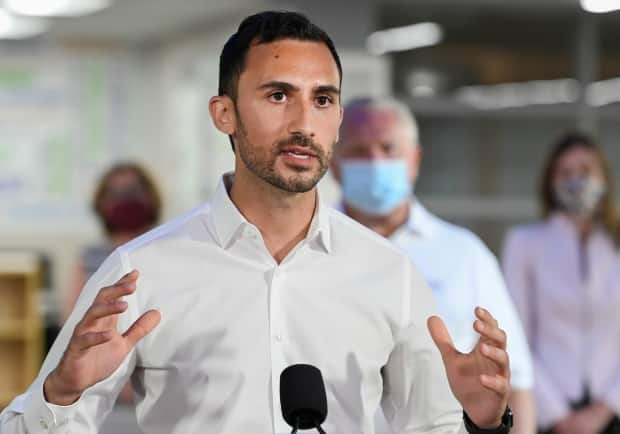

(Kwadwo Kyeremanteng - image credit)

A third wave of COVID-19 in Ontario may be inevitable but this time around, many experts say the province's schools should stay open.

Recent modelling from both provincial and federal health experts suggests that more transmissible novel coronavirus variants could soon cause a surge of infections not yet seen in the pandemic.

On Friday, the Public Health Agency of Canada said if restrictions are relaxed, as many regions are doing, there could be 20,000 new cases per day by mid-March.

That is the spectre haunting the return to in-person learning in Ontario, as students in the province's hotspots begin their first full week back.

But even if a new wave of COVID-19 materializes, medical experts from across the country are urging authorities to keep students in the classroom.

"I don't even think it should be a debate," Dr. Kwadwo Kyeremanteng, an intensive and palliative care physician in Ottawa, said in an interview.

"Our kids need to be at school."

Kyeremanteng believes schools are too important to close, the risk of transmission there has proven to be low, and if services such as take-out food and Amazon delivery can be protected, so can in-person learning.

"I would approach it as if it's an essential service," Kyeremanteng said.

Safer than being home?

Dr. Jennifer Grant, a Vancouver-based infectious disease specialist, agrees that schools have remained safe for students and teachers during the pandemic.

In fact, she says it may even be safer with kids in class, where they're made to follow public health guidelines and cases of COVID-19, if they do occur, are easier to trace and isolate.

"If the aim is to stop community spread, it's entirely possible that keeping schools open is the safest approach," she said in an interview.

"Children are supervised, they're kept in individual cohorts, parents don't have to rely on informal arrangements. Losing control over that organizational factor could conceivably make things worse."

A George Webster Elementary student in Toronto as the school prepared for the return to in-person learning last year.

Closing schools undoubtedly makes things worse when it comes to both the mental and physical health of children, Grant and other experts say, citing a growing number of studies documenting increases in childhood anxiety, depression and abuse during the pandemic.

There's also educational regression for the many students who haven't been able to thrive in a virtual classroom.

This is happening while a significant number of children have disappeared from the public education system altogether. At the Toronto District School Board, the country's largest, there are approximately 5,500 students (roughly 2 per cent of total enrolment) who have failed to present for either in-person or virtual learning.

"It's going to have lifelong implications," Grant said.

"Our children are a critical and precious resource that need to be considered as importantly as anybody else in society," she added.

Grant has signed a petition from the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of Children, titled Right to Education During COVID-19 along with nearly 140 other medical experts from across Canada. They're urging authorities to keep schools open. The petition cites academic studies on the negative impact of that current school closures are having on students, including lower test scores and even an expected drop in annual earnings as adults.

Latest school closure 'not justified'

It's widely accepted that last spring's school closure was the right move. COVID-19 was a frightening new disease and very little was known about how to contain the virus that causes it.

But there is less support for the Ontario government's decision for a province-wide school closure in January, which lasted six weeks in some regions. Although infections were surging to record highs at the time, more was known about the virus and there was a rigorous safety structure in place..

"We shouldn't have closed down schools," Kyeremanteng said. "What we were doing to our kids was not justified."

Dr. Ari Bitnun, an infectious disease physician at Toronto's Sick Kids Hospital and professor at the University of Toronto, also believes that schools could have safely remained open during the second wave.

"My own view is that there was no need for us to have kept schools closed after December."

Bitnun says there's no evidence of large outbreaks taking place in schools and that safety measures already in place "can go a long way to keep schools open, even if incidence goes up overall in the community."

Keeping schools open

He adds that schools could be made even safer with more targeted testing, the further study of transmission, and more mitigation measures.

It's something that teachers unions have repeatedly demanded, along with smaller class sizes.

According to the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario (ETFO), which represents 83,000 public educators, the province's schools still lack adequate layers of protection. Without them, the union says another closure is possible should there be a third wave.

"To safely reopen schools, and to keep them open, which is everyone's goal, the province must prioritize safety over political grandstanding," reads an ETFO statement from Feb. 3 responding to the government's decision to return to in-person learning.

Ontario Education Minister Stephen Lecce makes an announcement regarding the government's plan for a safe reopening of schools in the fall due to the COVID-19 pandemic at Father Leo J Austin Catholic Secondary School in Whitby, Ont., on Thursday, July 30, 2020.

For its part, the government of Premier Doug Ford has pumped more than $1 billion in additional funding into the education system, along with the implementation of strict safety measures, including mandatory masks at all times.

Education Minister Stephen Lecce and the government "are on the side of parents and medical experts who believe that we must keep schools safe, and by extension, open in this province, as it is vital for students mental health and development," Caitlin Clark, a spokesperson for the education minister, said in a statement.