Scientists who tested soil in Kristin Smart case used method in another murder. Is it legit?

The scientists who pitched in on the search for Kristin Smart’s body and say they found evidence of human decomposition near Susan Flores’ yard used the same method to help investigators on a double murder in Yakima, Washington.

And they say their chemical tests of a site where two bodies were discovered showed similar results to what they found near Flores’ property.

They’re hoping the experimental method one day develops into a proven way to help find buried bodies and end the anguish of families searching for answers, but so far it’s only been used in a handful of forensic cases.

Smart disappeared from Cal Poly on May 25, 1996 — 28 years ago — and despite Susan Flores’ son Paul Flores being convicted of her murder, her body has never been found.

If the soil testing could help locate Smart’s remains, it would be a landmark accomplishment for the fledgling approach.

Environmental engineer Tim Nelligan, environmental chemist Steve Hoyt and former FBI chemist Brian Eckenrode and former federal prosecutor Tim Perry formed a team to test the soil along the shared fence between Flores’ yard and her next-door neighbor’s property to try to locate signs of Smart’s body. The team believes they have found strong evidence of a “human decomposition event” centered at the fence through multiple tests they’ve conducted from February 2020 to March 2023.

After articles on their testing were published in the Los Angeles Times and The Tribune, the men were contacted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office about another murder case.

Six months later in September, federal court records show, they participated in the federal search warrant for the Washington case, performing the same tests and finding elevated levels of the same decomposing human body compounds as they did near Flores’ Arroyo Grande yard.

“There’s an opportunity for scientists and the community to aid and to use all the tools. What we feel is that we’ve come upon an opportunity here where we have a tool that could help not only just (find Smart’s remains) — we think really this could be Kristin’s legacy,” Nelligan said. “There are other cases such as Yakima or other areas where we can advance this technology.”

As part of The Tribune’s Reality Check series, The Tribune investigated how the testing works and whether it can accurately detect a human body.

Human bodies in Yakima yield similar vapor results to Flores’ yard, scientists say

The men were recruited to test their method in a Washington drug smuggling case that turned deadly in 2022 after the Department of Homeland Security began investigating a crime organization suspected of running narcotics from Mexico to Yakima, court records show.

As part of the investigation, agents spoke with two members of the organization, Cesar Murillo and Maira Hernandez, in December 2022. They were killed shortly after.

In January 2023, agents unsuccessfully searched a 71-acre ranch for their remains, before hiring Nelligan, Hoyt and Eckenrode in August.

Prosecutors obtained the warrant citing a new scientific approach that could help find human remains, and a judge approved it, The Tribune confirmed.

Nelligan told The Tribune that on Aug. 30 the three placed around 30 soil testing probes in several areas of interest on the Yakima property.

The scientists’ results showed two probes returned positive results for several of the human remains compounds they have identified. Those probes ended up being near the female body — one 5 feet away and the other 10.

Authorities returned to the ranch Sept. 13 to dig the area of interest the probes identified, but at the same time through other means, they determined the location of both bodies, which were dug up and removed the next day.

Despite the locations of the bodies known, the scientists received permission to return to the site on Sept 18 to test the soil composition.

The results from the tests near the bodies showed similar compounds to what was found near Susan Flores’ yard.

“I was not really surprised when we found the same groups of compounds up in Yakima where there were actually bodies buried,” Hoyt said.

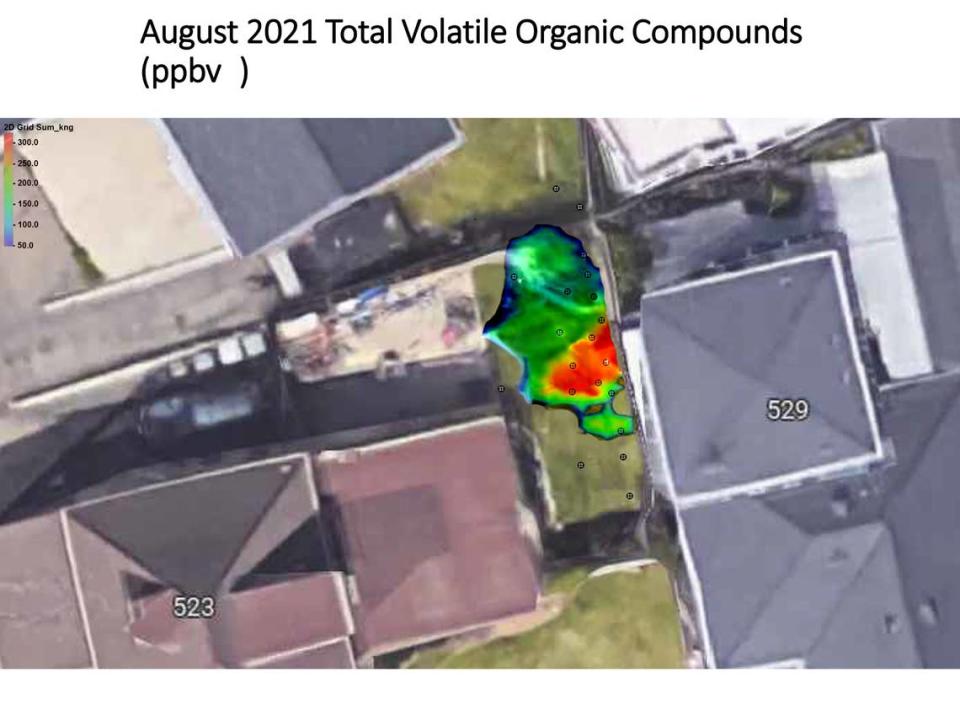

The scientists tested for 44 chemical compounds that they say were emitted from decomposing human remains near Flores’ yard and in Yakima.

Near Flores’ yard, 20 to 32 compounds were detected in various probes near the fence line, while four to seven compounds were detected in the control areas near Flores’ yard 119 to 3,300 feet away.

At the Yakima testing, 22 to 25 compounds were detected near Murillo’s body, while 14 to 29 compounds were detected near Hernandez’s body. The control areas, which were 3,600 feet from Murillo’s body and 1,600 feet from Hernandez’s body, detected 13 to 20 of the compounds present.

In addition to the increased number of compounds, the concentrations of some were also higher at the burial sites than in the control areas.

For example, samples of carbon disulfide, one of the compounds associated with human body decomposition, recorded near Murillo’s body tested as much as 13 times higher (1.79 to 48.73 micrograms per cubic meter) vs. the control site (0.8 to 3.64). The levels tested up to six times higher near Hernandez’s body, 1.88 to 21.86.

For another compound called pentanal, levels were up to six times higher near Murillo’s body (1.08 to 11.39 micrograms per cubic meter) vs. the control site (0.62 to 1.81). Levels near Hernandez were as much as three times as high as the control site at 0.96 to 5.71.

The tests near Flores’ yard showed even more dramatic differences for pentanal, 5.49 to 203.61 micrograms per cubic meter or 26 times higher than the 3.2 to 7.64 micrograms recorded in the controls.

Eckenrode told The Tribune that the way the data is evaluated is both qualitative and quantitative, meaning both the number of different compounds present and amount of each detected is part of their analysis.

Presence of one or few compounds is not enough to determine whether a body present, he said.

Soil composition can vary from place to place, Eckenrode said, so comparing their samples to the controls is key to figuring out whether human remains may be present.

How does the test work?

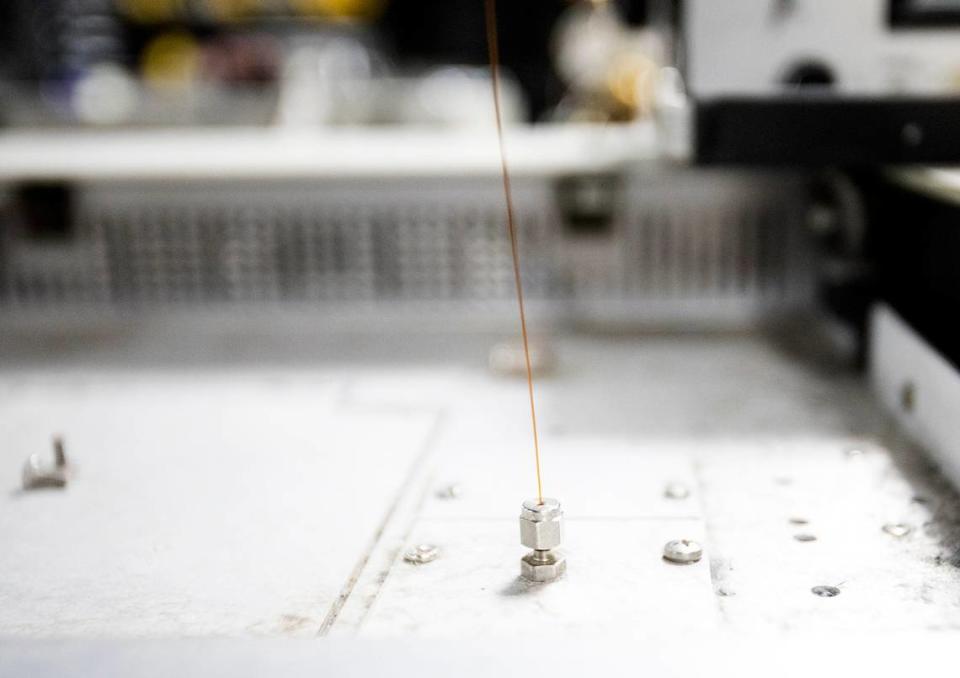

The soil investigation method used by Nelligan, Hoyt and Eckenrode is known as “vapor intrusion” testing.

It’s used by both the federal and state environmental protection agencies regularly to test for environmental pollutants, and the method is standard for soil pollution in particular, according to Andrew Leavitt, a senior engineering geologist with the Department of Toxic Substances Control at the California EPA.

The samples are taken by drilling holes in the ground, inserting tubes into the holes and connecting the tubes to a canister, known as a probe. The canister is then sealed, excess air is expelled and soil vapor pumped in.

The sampling tubes, which are set lengths, can go anywhere from 5 to 15 feet down, and the process typically takes two to 48 hours, Leavitt said, depending on the sample.

The sample is then taken to the lab, where the vapor is examined in a mass-spectrometer, a tool that measures and identifies gasses to create a unique profile of the vapor’s source.

“The mass-spectrometer will fragment each of the compounds coming out and create a fingerprint of the compound,” said Hoyt, who led the testing for the team and has been administering this method for more than two decades.

The method tests for soil vapor from a specific source, Leavitt said. If that source were to be removed, the vapors should eventually disperse and become less detectable or even undetectable.

A natural breakdown of the compound can “take a lot longer” and varies depending on the compound, Leavitt said, giving the example of PCE, also known as “forever chemicals,” which have polluted soil and groundwater below and around dry cleaners even after dry cleaners stopped using the chemical or the business closed.

Eckenrode said vapor begins to move right away after a source is removed, but soil can slow down that dispersal and vary depending on the moisture and temperature of the ground. He added that the bodies in Yakima had been buried for a year, and they were able to detect high concentrations of compounds 18 inches away five days after the bodies had been removed.

Leavitt said the compounds would test strongest near the source, but he also said it’s unclear how fast and how far soil vapor compounds move in soil.

Eckenrode added that this method is a much less invasive way to search because the testing does not disturb a property to the same extent as search methods would.

Humans must have distinct vapor profile for method to work, EPA scientist says

“Very hypothetically” speaking, Leavitt said, this sampling method could be used to identify where human remains are buried, though with one caveat: A decomposing human body must have a unique soil vapor profile that could not be confused with anything else.

Pigs have been used in the past to train cadaver dogs, and while research shows the profiles are similar, most studies found humans have a singular soil vapor profile of their own.

A 2018 study by the Centre for Forensic Science at the University of Technology in Australia found pigs and humans had “dissimilar” profiles, but that “in cooler conditions the results from each species became more comparable, especially during the early stages of decomposition.”

Despite this assertion, however, most studies indicate the topic needs more research. There is currently no standard profile to test for — some studies test for different compounds — and little information on the significance of the amount of each compound.

“Do we really know the chemistry that uniquely defines a human?” Eckenrode said. “My answer has to be, not quite. However, our results are indicating we’re getting closer.”

The men based their human decomposition vapor profile off of two of Eckenrode’s co-authored studies with the Tennessee Body Farm, a body donation program at The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, that studies decomposing bodies. The first study was a “decompositional odor database” published in 2004, and the other was an odor analysis of buried human remains published in 2008.

Their profile was also derived from a 2017 study called “The Odor of Death: An Overview of Current Knowledge on Characterization and Applications,” co-authored by several experts in the field.

Soil vapor science was litigated in Casey Anthony trial

Although the science is not definitive yet, the Yakima case is not the first case where it has been used.

The materials the scientists tested for are known as volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. They are gas molecules that have a high vapor pressure and low water solubility, according to the EPA.

Many VOCs are human-made chemicals used and produced in the manufacture of paints, pharmaceuticals and refrigerants, while others emit from the natural decomposition process of living organisms.

The compounds were litigated briefly in the trial against Flores during testimony from cadaver dog handlers, who said their dogs alerted to human remains VOCs in Paul Flores’ dorm room and underneath Ruben Flores’ deck.

But the handlers who testified were experts in cadaver dog training, not the chemical analysis of these compounds.

This science did play a large role in the 2011 Casey Anthony trial in Florida. In the high-profile case, Anthony was accused of killing her 3-year-old daughter and burying her behind her parents’ Orlando home.

Prosecutors called scientist Arpad Vass to testify about alleged human remains VOCs detected in Anthony’s trunk to prove Anthony transported her dead child in her car.

Vass was working in a federal lab at the time of the trial, according to his testimony, and co-authored both papers with Eckenrode that were cited in the current testing in Yakima and near Flores’ yard.

Vass testified that VOCs consistent with human decomposition were detected in the trunk. But forensic chemist Kenneth Furton, who the defense called as a witness, countered that testimony by saying the VOCs could have been emitted from trash in the trunk.

Anthony was ultimately acquitted, and Vass told The Marshall Project, a criminal justice news nonprofit, that the trial destroyed his career and paved the way for the federal lab he worked for to fire him.

In an email to The Tribune, Vass claimed he was the first person to begin researching the use of VOCs for forensics. He claimed Anthony’s defense attorney, Jose Baez, said Vass was right during closing arguments, “so YES, (the science) has been used in the courts and deemed acceptable.”

In Baez’s closing arguments in the case, he called Vass a “scientific explorer trying to market his invention” and accused the prosecution of trying to win the high-profile case at any cost.

In the years since the Anthony trial, several studies — including those by Furton — do indicate humans have specific VOC markers, but they have not yet been used in actual forensic settings beyond training cadaver dogs.

Cadaver dogs can help confirm science, expert says

Furton told The Tribune that he was called to speak about the science of VOCs alone. The science at that time — and today — is not proven enough to indicate on its own where a human body is or was, he said.

“If (Eckenrode, Hoyt and Nelligan) are saying these compounds — because they’ve seen them in confirmed cases — are evidence of human remains, my question is, how accurate is that?” Furton said.

Currently, he said, the testing and literature are not strong enough to say which compounds — and how much of each compound — is related to human body decomposition and nothing else. Much of the research has been confirmation of bodies that scientists know are there, but there hasn’t been as much research on testing for these compounds when a body isn’t present to confirm the compound profile is unique.

It’s clear that the compounds Eckenrode, Hoyt and Nelligan tested for are present in decomposing human bodies, Furton said, but those compounds can also appear in other substances or decomposition processes.

There is one tool Furton said has about 90% accuracy: cadaver dogs.

Furton has researched cadaver dog accuracy throughout his decades-long career.

“I don’t have any doubt that there are human specific VOCs because canines can do it,” Furton said, adding that the science needs more work to confirm a human VOC profile.

Furton said when he testified in the Anthony trial, he was not asked questions about the two cadaver dog alerts to the trunk.

Had he been asked, Furton said, he would have said the dog alerts plus Vass’ science combined were a strong indication that a body may have been in Anthony’s trunk.

“If you were to get a positive alert from the dogs as well as the chemicals backing them up, then that’s pretty powerful evidence,” Furton said. “But the instrumental method by itself, I think it’s still experimental.”

Have cadaver dogs alerted in Susan Flores’ yard?

Susan Flores’ yard has been searched multiple times in the past 27 years — once in 1997 for the civil suit, in 2000 by the Sheriff’s Office and again in 2007 during the civil suit, Chris Lambert, host of the “Your Own Backyard” podcast that investigated the case, told The Tribune.

Adela Morris, a dog handler who helped with searches at Paul Flores’ dorm and Ruben Flores’ home, said in the preliminary hearing for the Floreses’ trial that she was involved in the 1997 search of Susan Flores’ yard.

According to her testimony, she said she wrote in her notes that her dog was trying to alert but “couldn’t pinpoint anything” and wrote “unclear to me” in her notes regarding her dog’s behavior toward unspecified wood. The dog also alerted in a corner of the property.

Morris’s notes at the time did not reflect where exactly on the property the alerts or alert attempts were, she said in her testimony.

“I think my dog was communicating to me something that I couldn’t help her with and I didn’t know how to read it,” Morris said in her testimony. “She was giving me body language and alerts and not pinpointing at anything.”

At that time she had 10 years of experience as a cadaver dog handler. She said the report she wrote then is not as detailed as it should have been.

Morris declined to interview with The Tribune for this story.

Law enforcement has never revealed the results of the 2000 search, and it is unclear if they commissioned cadaver dogs at that time.

The 2007 search for the civil suit used ground-penetrating radar, but Flores denied the Smart family’s lawyer’s request to bring cadaver dogs, Lambert said.

In 2014, Lambert said, a retired cadaver dog alerted against the fence line at the yard behind Flores — a different home than where the scientists have been testing. The dog retired from cadaver work in 2009, Lambert said, and his alerts could not be taken seriously by law enforcement because the dog’s certification had not been renewed for five years.

Can investigators dig up Susan Flores’ yard?

Nelligan said they have shared their findings with the San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Office, but the agency told The Tribune it could not comment on the investigation as it is still active.

Det. Greg Smith told The Tribune in July that the science the men presented amounts to a theory rather than evidence.

“My job is to either validate what they’re saying or find another expert to say that what they’re doing is correct or what they’re doing is sound science or not,” he said. “And that’s where we are in the process.”

According to experts also interviewed by The Tribune in July, the biggest challenge in this case is not necessarily obtaining a search warrant, but rather successfully litigating the science that could be the foundation for a warrant.

The majority of the three-month criminal trial against Paul Flores and his father, Ruben Flores, revolved around similar scientific disputes.

The prosecution argued there was a clandestine grave with traces of blood beneath Ruben Flores’ deck and used dog alerts for human remains to make its case, among other forensic evidence. Defense attorneys argued this evidence was “junk science” inaccurately framed to convict their clients.

Susan Flores, whose property is at the heart of this question, declined to comment on the scientists’ findings through her son’s attorney, Harold Mesick, who also declined to comment.