The Second Coming Of Surrealism Is Here

Something strange is happening in fashion.

Step inside Schiaparelli in Paris on the Place Vendôme and you will find an exquisitely tailored, black double-breasted blazer that boasts, on closer inspection, a lovingly sculpted pair of gold nipples for a top row of buttons. Note, also, the chic box-frame handbag with a snap closure in the shape of a disembodied nose. You will probably have spotted that the shoe of the season is Loewe’s balloon pump, so densely encrusted with deflated balloons that they could be ruffles or a shower of fallen petals. And you might remember that, at Moschino’s latest show, Jeremy Scott took the catwalk’s oldest adage – that clothes reflect the times we live in – and fashioned it into a visual pun.

‘Everyone’s talking about inflation,’ he said in Milan that night. ‘The cost of everything’s going up: housing, food, life. So I took inflation into the collection.’ Cue a menagerie of pool inflatables – a turtle, a tiger, a flamingo – stacked, totem-pole style, over a cocktail dress.

This is not mere whimsy, or common-or-garden oddness. It is nothing less than the second coming of surrealism.

‘This summer the roses are blue; the wood is of glass,’ wrote André Breton in 1924’s Manifesto of Surrealism. Breton would have been in his element at the Loewe show, where a giant red fibreglass anthurium flower towered over the catwalk. (The surrealists, who loved their Freudianisms, would have appreciated the anthurium, that most phallic of blooms.)

The brand where Elsa Schiaparelli created some of the greatest artefacts of surrealism in collaboration with Salvador Dalí – the shoe worn as a hat, the iconic lobster dress – was officially relaunched back in 2014, but it was only when the American designer Daniel Roseberry took the helm five years later, and zoomed in on disembodied body parts rendered in gold as a surreal house signature, that the Schiaparelli name stepped out of the history books and onto the red carpet, worn by everyone from Beyoncé and Michelle Obama to Julia Fox and our cover star Emma Corrin.

With its disembodied ears (Schiaparelli), keyboard buttons used as sequins (JW Anderson) and monster-sized zip pulls (Louis Vuitton), surrealism is not exactly what you might call an obvious choice in an industry where glamour, elegance and sex appeal are the preferred currencies. And yet it is one of the breakout trends of the season, catching our imagination by holding up a hall of mirrors to our lives.

Surrealism, which delights in mashing up everyday reality with our dreams and unconscious desires, feels entirely contemporary in our fake- news, post-truth, social-media-inflamed universe. André Breton wrote, ‘I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality.’ Is it just me, or does that sound uncannily like a description of Instagram and the way social media has rewired our brains? In a cartoon- ish political culture where news headlines frequently have a you-couldn’t-make-it-up ring to them, surrealism is an aesthetic reflection of the insanity of our reality.

Surrealism was born in opposition to the ‘rationalism’ that some artists and thinkers believed had guided Europe into World War I. Surrealists wanted to give the thoughts and ideas of the subconscious, irrational mind their place in culture alongside logic and tradition. It was a visual movement, drawing on the fragmented pictures of dreams and on unconventional depictions of the human body, and soon forged a deep connection with fashion.

Elsa Schiaparelli was a successful fashion designer and Salvador Dalí a young artist when they met in 1930s Paris. ‘Schiap’ gave Dalí access to wealthy benefactors; Dalí gave Schiaparelli an artistic credibility and an edge in her great rivalry with Coco Chanel. Together, Dalí and Schiap became a powerful force in the avant-garde culture of that decade.

In the intervening century, surrealism never entirely disappeared from fashion.

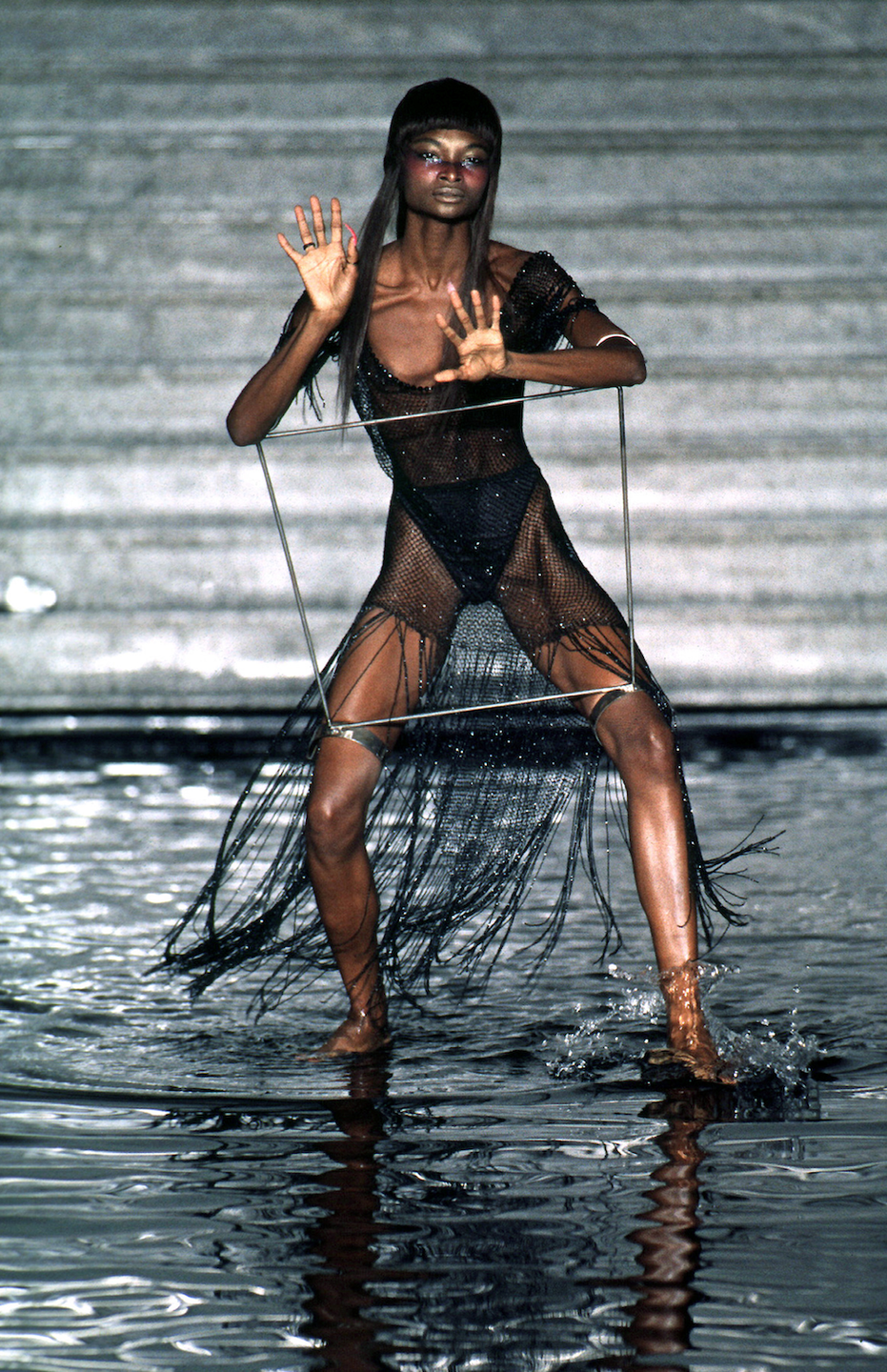

Alexander McQueen’s SS97 collection, La Poupée, was inspired by the distorted dolls in the photo- graphs of surrealist artist Hans Bellmer. The 2010s craze for fur-lined shoes – shaggy sliders at Phoebe Philo’s Céline in 2013, furry loafers at Gucci two years later – owed something to Méret Oppenheim’s iconic Luncheon in Fur artwork of 1936, which depicted a teacup lined in gazelle pelt. But the mainstream fashion industry wasn’t always keen. When Opening Ceremony collaborated with Birkenstock in 2014 on a range of shoes printed with images from René Magritte’s unsettling paintings, a headline in the Huffington Post asked, ‘Are these the ugliest shoes of all time?’

It was in 2016 that the pendulum began to swing back toward surrealism. That year, the American dictionary Merriam-Webster named ‘surreal’ as its Word of the Year. Virgil Abloh, who joined Louis Vuitton as artistic director of menswear in 2018, sent out invitations for a menswear show in the form of clock that ran anti-clockwise; the show space and the clothes were covered in idealised white clouds scud- ding across a blue sky in homage to Magritte.

That show was in January 2020. And, well, we all know what happened next. Within a few months, reality entered an era of unprecedented strangeness with a global pandemic that put an emergency brake on life as we knew it. When the world started turning again, many in fashion predicted a return to the Roaring Twenties: sequins and dancing shoes, short dresses and late nights. As it turned out, we did get a return to the vibe of that decade – but in an unexpected form. It was the surrealist artists of that time, rather than the flapper girls, who fashion designers channelled to reflect the ‘wait, what on earth just happened?’ mood of the times.

Jonathan Anderson spent his first eight years at Loewe leaning into an artisanal luxe vision of linen-and-raffia chic until, in 2021, he performed a handbrake turn into high-gloss surrealist style and turbocharged Loewe from an insidery favourite to a fashion powerhouse. In the SS22 show, sandals featured high heels sculpted in the form of broken eggshells, of lipsticks, of a single rose. With each show since, Anderson has pushed further into surrealism. Elsewhere, AW22 saw a cosy, squishy puffer coat incongruously printed to resemble Dresden china at Dries Van Noten; at Moschino, models appeared dressed as grandfather clocks, as upholstered arm- chairs and as lacquered screens. By the time London Fashion Week rolled around in September last year, a dress made to look like a plastic bag containing a goldfish – as seen at JW Anderson’s own-label show, held in a Soho video-gaming arcade – had become the sort of thing front-row regulars have learnt to take in their stride.

And it’s not just our wardrobes that have taken a strange turn. The food scene has fallen hard for star chef Laila Gohar’s surreal canapés. Butter pats in the shape of fingers, chairs made from sponge cake and edible ant sculptures crafted from maraschino cherries have made her the hottest chef and food designer in New York, beloved by the art and fashion worlds. Surrealism’s revival can be seen on our mantelpieces – the bottoms and breasts of those Anissa Kermiche vases that are now a modern must-have would have tickled Magritte and Dalí – and on our walls. The vogue for surrealist art is spelled out in the prices being fetched at auction. In March last year, René Magritte’s painting L’Empire des lumières – a paradoxical scene of a lamp-lit, nocturnal house beneath a blue and sunny sky – sold for £59.4 million, tripling the previous record price for the artist. Two months later, Man Ray’s surrealist portrait Le Violon d’Ingres sold for £10 million, the highest price ever paid for a single photograph.

Daniel Roseberry has said that in his first year at Schiaparelli, spent in the feverish uncertainty of the early days of the pandemic, he sometimes felt like he was designing for the end of the world. Thankfully, the world came back to life – and so did fashion. Yet, what we call the ‘new normal’ is anything but. Weird is the new wonderful.

You Might Also Like