See inside a $300 million Gilded Age mansion built for heirs who died on the Titanic that sat abandoned for years

In 1897, Peter Widener built a mansion near Philadelphia with 32 bedrooms and 28 bathrooms.

Some of Lynnewood Hall's intended residents tragically perished aboard the Titanic.

The mansion housed Widener, his surviving heir, and a church before falling into disrepair.

Tucked away in a quiet suburb of Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, lies Lynnewood Hall, a more-than-century-old mansion that its owner once referred to as "The Last American Versailles."

In 1897, Peter A. B. Widener, a millionaire who made his fortune via the butcher and transportation industries — and a major investor in the Titanic — commissioned the construction of the 34-acre estate.

He intended Lynnewood Hall to be a residence for him, his two sons, and their families. However, fate had other plans.

In 1912, Widener's son George, his daughter-in-law Eleanor, and their son Harry boarded the Titanic for their return from a trip to Europe. Tragically, George and Harry, along with hundreds of other passengers, perished when the ship sank to the ocean floor.

Widener continued to live in the home, eventually passing away from health complications in 1915. Lynnewood Hall was later inherited by his surviving son, Joseph, who was married and had two children. Following Joseph's death in 1943, the mansion cycled through several owners, including the First Korean Church of New York.

A pastor of the First Korean Church of New York, Richard S. Yoon, listed the home for sale in 2014. It remained unoccupied for several years and attracted the attention of numerous urban explorers, including Leland Kent, the blogger behind Abandoned Southeast, who ventured into the mansion in 2019 and snapped dozens of photos of the dilapidated interiors.

In June 2023, the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation purchased the estate from Yoon for more than $9 million. According to Edward Thome, the group's CEO and executive director, the foundation plans to restore the estate to its former glory.

Take a look inside.

The estate is about 34 acres, equivalent to more than 25 football fields.

On the estate is Lynnewood Hall, spanning 110,000 square feet; Lynnewood Lodge, covering 18,000 square feet; and the Gatehouse, occupying 15,000 square feet, according to Thome, the head of the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation.

In addition to its 32 bedrooms and 28 bathrooms, Lynnewood Hall has a 1,000-person ballroom, an indoor swimming pool, and multiple fountains and gardens.

The estate used to be surrounded by world-class gardens.

The estate's original gardens were designed by head gardener William Kleinheinz, according to the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation.

However, between 1914 and 1916, at the request of Joseph Widener, the home underwent extensive renovations. As part of this project, Jaques Greber, a distinguished landscape architect of his era, added French-style gardens to the property.

The home's construction cost $8 million when it was built in 1897, according to Thome. That's over $300 million in 2023 dollars, accounting for inflation.

Although many of Lynnewood's original furnishings and decorations have either been removed or degraded over time, it was once a masterpiece.

Widener entrusted its design to Horace Trumbauer, a then-29-year-old architect.

According to the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation, the home has a Florentine bronze front door, and its main hall features marble and Caen stone, a limestone extracted from nortern France.

The Duveen Brothers, famous art dealers, furnished the majority of the home's interior, providing carved wood paneling from a French chateau, furniture sourced from Versailles, and tapestries previously owned by European aristocrats, the foundation said.

No detail was spared in the construction of the mansion.

Widener came from humble beginnings. He began his career as a butcher's apprentice and later established one of the earliest meat-store chains in the nation.

According to the historical website House Histree, he started to build his wealth by receiving a $50,000 government contract to provide meat to the Union Army during the Civil War.

Later in life, he helped start the Philadelphia Traction Company, which built public transportation systems in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago.

He was also a philanthropist, funding libraries and establishing the Widener Memorial Home for Crippled Children, according to the Philly History Blog.

Widener also collected fine art and had a gallery built in the home that featured numerous world-renowned paintings, including several by Claude Monet and Rembrandt, the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation said.

After assuming responsibility for the Widener art collection upon his father's passing, Joseph welcomed the public into the home from 1915 to 1940. When he passed, the family's collection was donated to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

The Great Hall’s soaring ceilings are decorated with carved crown molding.

Kent, the blogger who toured and photographed the mansion in 2019, told Business Insider that the home was unlike anything he had ever seen before.

"Any place that you go into that's large and dark has a spooky vibe to it," Kent said. "But as soon as your eyes adjust and you explore with a flashlight or walk through areas where there's sunlight, you can really see the material and the beautiful space."

The main architectural style of Lynnewood Hall is called Palladianism, according to Thome.

Palladianism, an architectural style popular in England from 1715 to 1760, drew inspiration from the works of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio.

This architectural style is deeply rooted in Roman and Greek influences, emphasizing symmetry and classical details.

Many rooms in the mansion are now empty, except for some vintage chairs or beds.

The ornate gold molding in the Reception Room looks similar to the wall decor found in many rooms throughout Versailles.

Some of Lynnewood Hall's dozens of bedrooms were designated specifically for staff.

This room was a governess suite, typically reserved as private quarters for a woman hired to educate and mentor children in an affluent household.

A bathroom in the home reveals how wealthy people lived in the early 1900s.

The lavish bathroom features towering archways, polished mirrors, decorative molding, and a sizable marble tub.

A guest bedroom on the second floor of the west wing had dusty furniture and a broken ceiling.

The primary living spaces for the Wideners were located in the west and east wings of the second floor, at the front of the house. Housing for the domestic staff was in the basement, on the first floor, and extended to the third and fourth floors.

Several rooms contain old suitcases and books left behind by former occupants.

When Kent, the photographer and blogger, visited Lynnewood back in 2019, the luggage in this room stood at the ready, as if anticipating its owner's imminent return.

An indoor pool lies in ruins.

The state of the pool is a testament to the mansion's years of neglect and decay.

There are two main staircases in Lynnewood Hall.

The front of the house rises two stories, while the rear is five stories, including the basement. In total, there are only two main staircases, but there are seven throughout the residence. Today, the servant staircase is the only one that extends from the basement all the way to the attic.

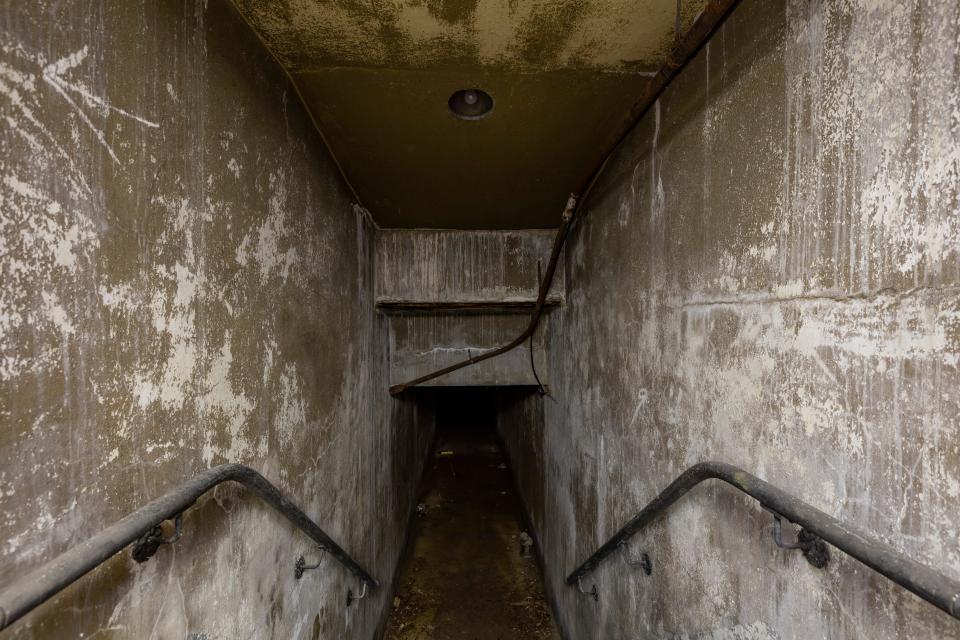

There are tunnels running under the property, linking various parts of the house.

Many large homes built during the Gilded Age often incorporated hidden passages, commonly referred to as servants' tunnels.

These tunnels served a dual purpose: not only did they ensure that servants could perform their duties without intruding upon the occupants' daily lives, but they also provided a comfortable way to move between different wings of the house during the frigid winter months.

"Usually in these types of homes, the staff were hidden from view," Thome told BI. "That's partially true in this house, but I would also say that there aren't as many back hallways and secret passages as you would imagine. The staff were a bit more public-facing in this home, which is unusual for the time, and has a lot to do with the fact that the Wideners were new money."

After years of neglect, the tunnels of Lynnewood Hall have taken on an eerie appearance.

"The tunnels are pitch black in both directions, and when you shine a light down there, the darkness seems to eat it up," Kent said. "You can only see about six to eight feet in front of you."

The Raphael room was turned into a classroom to educate seminary students from 1952 to 1996.

In 1952, a faith-based Christian organization, Faith Theological Seminary, purchased the mansion for $190,000, as reported by the weekly newspaper, the Chestnut Local. Adjusted for inflation, that is roughly equivalent to $2.2 million in 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For the next 44 years, hundreds of ministers and Christian leaders were educated on its premises, the seminary's website said.

However, in 1996, due to financial challenges, ownership of the mansion was transferred in a sheriff's sale to Richard S. Yoon, pastor of the First Korean Church of New York and a former chancellor of the seminary.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in 2013 that Yoon had previously loaned the seminary $2.2 million to pay the mansion's mortgage.

The original kitchen was repurposed to cater to the hundreds of seminary students that studied at Lynnewood Hall over the years.

In 2019, when Kent explored the mansion, plates, spoons, and cups had been left in the kitchen, as if frozen in time.

The seminary students shared meals in this dining hall, according to Thome.

While the dining hall still looks dated, the table and chairs appear modern set against the rooms with elaborate molding.

A ballroom was transformed into a place of worship that was in good condition as of 2019.

Yoon aimed to establish a branch of his congregation at Lynnewood Hall but encountered various obstacles along the way, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

After legal battles and the church forfeiting its tax-exempt status over allegations of not using the property for religious or educational purposes, Yoon chose to sell it.

He listed the mansion for sale in 2014 for $20 million. Despite significant interest, including inquiries from movie stars and millionaires, according to the Inquirer, Yoon refused to sell, leaving the home neglected for many years.

However, in 2023, he finally agreed to sell the property to the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation for $9 million.

The Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation has plans to revive the 127-year-old home.

The foundation has a three-part plan to restore Lynnewood Hall.

First, acquire the hall — a goal the foundation achieved in 2023.

Second, it will focus on the grounds, adding formal gardens and restoring the building exteriors. Third, it will renovate the interior, expand amenities such as the art galleries, and create venues for public events.

Altogether, the project is estimated to cost around $110 million, according to Thome. The funds will be raised via crowdfunding and donations.

"This has been a lifelong project for me," Thome said. "All of us at the foundation really view ourselves as stewards of the property."

The library looks clean and well-kept after the foundation cleaned it up.

The estate is meticulously restoring one room at a time to its historical beauty.

"It's really one of the most important residential architectural buildings in the country, and the fact that it's completely unknown is absurd," Thome added. "We aim to change that and return it back to the community as a piece of public art for educational, and recreational resources."

Read the original article on Business Insider