Seeking therapy, they found a Rubik's Cube community instead. It saved their son's life.

There are few puzzles out there as iconic and recognizable as the Rubik’s Cube. A twistable block covered on all sides with colored squares meant to serve as a puzzling brain teaser, the Rubik’s has delighted some and frustrated many since its creation in 1974. Some of us are even pretty good at solving one, dusting off the skill when in need of a party a trick or a “fun fact” to share at the office.

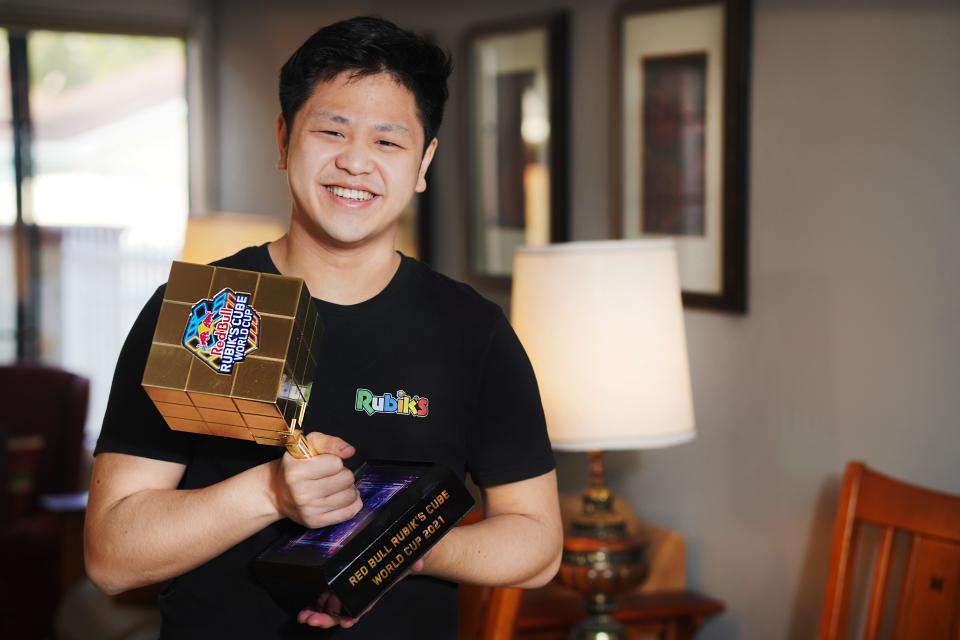

For Max Park and his family, however, the iconic colorful blocks are a symbol of much more. In fact, Park’s parents credit the activity, known as cubing, and the community built around it with saving their son.

“Basically cubing has saved his life. It has just been an unbelievable teacher for Max,” father Schwan Park told USA TODAY.

Max, a 21-year-old California native, was declared the new world record holder earlier this month after solving a 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube in a matter of 3.13 seconds, surpassing former champ Yusheng Du’s time of 3.47 seconds. A master of what is known as “speedcubing,” Park has broken 69 records to date, according to his father, and is a standing member of the Guinness World Records Hall of Fame. Currently the holder of multiple active cubing-related titles, Park has been recognized for solving the 4x4x4, 5x5x5, 6x6x6 and 7x7x7 cubes in record time, finishing the latter in a matter of 1 minute and 35 seconds.

While cubing has been a passion of Park’s, whose motto is “don’t think, just solve,” for more than 10 years now, it all started as a form of therapy.

21-year-old breaking Rubik's Cube record Watch 21-year-old solve Rubik’s Cube in astonishing 3.13 seconds, setting new world record

Cubing as therapy

Max was diagnosed with autism at the age of 2, prompting parents Schwan and Miki to seek new ways to help their son develop different skills.

Early in life, Max struggled with fine motor movements and began working with an occupational therapist to help strengthen his fingers. It was during the course of this therapy, when Max was about 9 years old, that Miki decided to hand her son a Rubik’s Cube that had been laying around the house. After learning the basics on YouTube, she taught Max how to use the puzzle and watched as the student very quickly surpassed the teacher.

“Max took the cube and he just gravitated towards it and just went down a rabbit hole,” said Schwan. “I mean, he really loved it, he needed to solve it, and so right away in about two days he was able to solve it. He learned very, very quickly. It was just something he loved.”

At the age of 10, Max’s parents brought him to his first cubing competition, believing it would be a good environment for Max not only to share his passion but work on things like socialization, learning non-verbal cues such as pointing, communication and recognizing social cues. Even waiting in line at the event served as valuable learning experience for Max, Schwan said.

Quickly, the family realized that the cubing community was much bigger – and much more welcoming – than they had realized.

“We took him to a cube competition and all of a sudden, he was pointing at some kids that he knew from YouTube. We just saw him light up and he totally found his tribe of people,” Schwan said. He and Miki immediately recognized these events as a potential “goldmine” of opportunities to help their son expand and grow his life skills.

“We’re sitting there always struggling to look for therapy sessions, to help him get socialized and here was a perfect venue," Schwan said. "The motivation was something that was just so helpful in helping him to develop everything that we had hoped he could achieve.”

First man diagnosed with autism dies Mississippi man Donald Triplett, first person diagnosed with autism, dead at 89

A master in the making

Max took to competitive cubing faster than even his parents could have imagined, winning the 6x6 cube contest at the second competition he attended. They were shocked to watch Max quickly outpace contestants three times his age, Schwan said, beating college-aged kids that towered over him in family photos from the time.

“The crazy part is we didn't even know he could do the 6x6, so when we found out that he won, we were like, are you kidding?” said Schwan. “I remember the delegate telling us ‘Oh, the time that he got is top 100 in the United States,’ and we were just blown away.”

From those first moments, Max and his family never looked back.

Now 21 and a record-breaker many times over, Max has no intentions of slowing down. In fact, besides being a well-recognized member of the World Cube Association, Max is also an official ambassador for the Rubik’s brand itself. He also appeared in a 2020 documentary titled “The Speed Cubers,” which explored the rivalry and friendship between Max and fellow world-renowned speedcuber Feliks Zemdegs.

As Max’s star grew, people began to recognize him not only at cubing competitions and gatherings but on the street, as well. Even this development, Schwan said, was an avenue for Max to learn and practice new skills.

“As he started getting more and more notoriety within the speed cubing community…. people were asking for his autograph. And we really had to work on that because, being on the spectrum, he sort of really doesn't get the kind of like the adulation and the fame part,” said Schwan.

After some therapy work and practice, Max got more comfortable meeting fans and got used to signing autographs and smiling for pictures. Though Max has gotten somewhat accustomed to the limelight, he still hesitates to appear on camera and often communicates with a mixture of verbal and non-verbal cues, meaning he isn't usually available to give his own interviews. But to Max, it isn't about the accolades or fame anyway, but rather facing the next challenge head-one.

Cubing as a community

Max’s latest landmark achievement with the 3x3 Rubik's Cube happened earlier this month, June 11, at Pride in Long Beach, a competition overseen by the World Cube Association (WCA). The non-profit is tasked with hosting and governing competitions for mechanical puzzles known as “twisty puzzles,” which are solved by twisting groups of pieces into place.

While Rubik’s is by and far the most famous example, the WCA selects a group of these puzzles for official events, which have been hosted in multiple countries across the globe. According to their website, the WCA has hosted more than 10,000 competitors from 140 different countries over the past decade, operating entirely with a volunteer-only team. The small but mighty organization offers not only a fair place for the best to compete, but a sense of community that has proven invaluable for families like the Parks.

“The speed cubing community, the WCA, we can't thank them enough,” said Schwan. “I mean, we even tear up sometimes just thinking about where our lives would be without this, because this has given back so much that most people don't even see. The little things, the little moments of success we are just so unbelievably grateful for.”

The community opened up to Max and his family from day one, Schwan said, providing an inclusive environment and a warm welcome. They helped and understood exactly how to help Max without even being told, something the family was especially grateful for 10 years ago, when the general public was less aware and educated on the topic of autism.

The Parks have also enjoyed watching the young people around them grow in self-confidence along with their son, noting that kids who may be called “nerdy” or “shy” often blossom after finding their “tribe” in the cubing community.

"They find themselves," Schwan said. "And not only do they find themselves, they get to know who they are and they like themselves very much, which I think is just unbelievably amazing.”

Future competitors

As for Max breaking more records, Schwan said it’s a very really possibility for the future.

Though he thinks 3.13 seconds should hold as the world's fasted for a while, cubing has always been about personal challenge as opposed to public adoration for Max, who will continue to cube competitively for as long as he loves doing it.

Though meeting Max at the competition table may seem a bit intimidating for speedcubing hopefuls, Schwan encouraged anyone with interest to give it a shot.

“My one piece of advice is just go," Schwan said. "It’s not just the competition and doing well at the competition, you're going to find yourself. It's going to be something that’s going to, possibly, define your life, as it did for Max.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How world-record holder Max Park found community with a Rubik's Cube