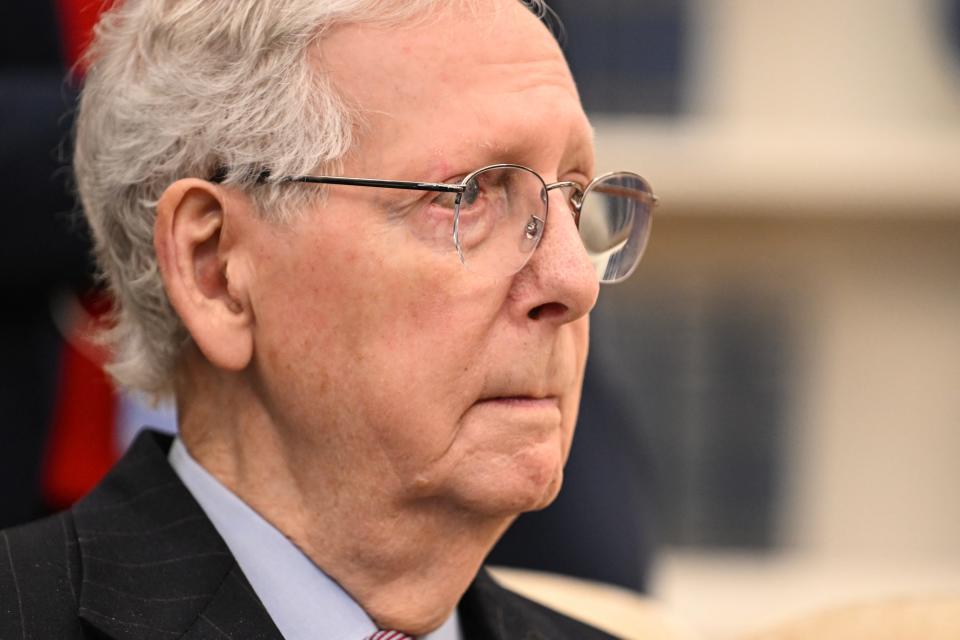

Sen. Mitch McConnell's retirement raises question: When is the right time to step back?

Mitch McConnell announced Wednesday that he would step down from his role as Senate Republicans' leader in November. The 82-year-old from Kentucky told his Senate colleagues, "One of life’s most underappreciated talents is to know when it’s time to move on to life's next chapter."

So how does one determine when to downshift or retire from their career, to relinquish the car keys, or to move to a condo so someone else can do the lawn and shovel snow?

Especially if finances are not a factor ‒ and, for many people, income and health are the two biggest determinants for retirement ‒ the decision depends on someone's values, how they see the future and how they want to be remembered, experts say. It can also depend on how well prepared they are for retirement, how productive they (and their peers) feel they are, and what kind of work they do.

"When we see our future as a horizon and that is shortening, our goals shift away from money, power, accomplishments, influence. We focus more on emotions, on legacy, on not wasting time on things that might rob us of our emotional well-being," said Dawn Carr, an expert in late-life productivity, social engagement and wellness.

She compared McConnell to someone who was in many ways his ideological opposite: Ruth Bader Ginsberg, the Supreme Court Justice who long resisted calls for her to retire and died in 2020 at age 87 while still on the bench.

"If you know your time is short, you might feel more urgency, and want to leave a legacy. If our jobs are giving us emotional satisfaction, we're less likely to step away and more likely to dig in," said Carr, a sociology professor at Florida State University and director of the school's Claude Pepper Center.

The announcement: Mitch McConnell, a colossal figure in Congress, will step down from his leadership post in November

That might describe an entire generation of America's political leadership, including Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., who died in office last year at age 90 after several years of ill health. President Joe Biden is running for reelection at 81 against former President Donald Trump, 77. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., is 73. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., the former speaker of the House, who remains in Congress, is a decade his senior.

"Our sense of leaving a legacy is about what we think the world needs going ahead," Carr said, speaking generally. "I would bet many politicians in the U.S. right now have really particular feelings about the future, and those feelings don't align. So they dig in because you believe you have to protect the country and its future."

Work longer, but take it easier?

Just because someone ‒ including an elected official ‒ slows down, doesn’t mean they’re incompetent or experiencing cognitive decline, said Dr. Amit Shah, a geriatrician at the Mayo Clinic. Americans of all professions are working until later ages.

As people get set to retire, Shah recommends a gradual, phased approach, as opposed to the old stereotype of trading the office for the golf range ‒ which could get boring fast for people used to an active life.

Reduced work hours, or transitioning to mentorship roles, can be fulfilling, particularly for people who have held leadership positions, such as a CEO or lawmaker, he said.“Part of that succession plan should be phasing yourself out and bringing in the new person,” Shah said. “It goes much better, oftentimes, if you’re able to guide. But you have to be willing to let go also.”Some countries have mandatory age limits to stop work. In the U.S., the decision is often left to people’s own choice. However, geriatricians recommend older people plan out their goals and consult with people they trust to monitor cognitive changes that might affect how they work.

“We want we want to support people who are perfectly capable of continuing to work later in life if that's important to them,” said Dr. Cathleen Colon-Emeric, chief of Duke University School of Medicine’s geriatrics division.

“We also want to make sure that we are identifying issues as they arise so that folks can make appropriate changes.”

Work, identity and 'a culture problem'

Older people have a lot to offer the workplace, FSU's Carr said, including institutional knowledge, longer-term perspectives, and a deep understanding of their field. Younger people, in turn, bring fresh perspectives, the ability to spot and work around longstanding problems, energy and vitality. Workplaces that combine all of those attributes are ideal, she said.

"It's not necessarily a question of this age or that age; it has to be about your commitment to the larger vision, the fabric of the organization around you and that you are still contributing to it," she said.

For many people, especially those in high-profile careers like politics or public service, their work is more than a job: It's a purpose, a calling, even an intrinsic part of who they are and how they see themselves.

Retirement can bring an identity crisis, particularly for men of McConnell's generation whose self-worth (for better or worse) often hinged on their ability to work and provide for their families.

"Women wear more hats, and in that way, we benefit from it," Carr said. "For a lot of men, stepping away from a career is akin to walking away from who you are. But we're good at adapting, and we can think about alternative activities, other ways of contributing."

The idea that retirement means diminishment is a false narrative, Carr said, and the trick is to find other ways to find meaning and purpose.

But that's often easier said than done, she acknowledged: "We don't have a lot of words to describe ourselves outside of work. And that's a culture problem."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Mitch McConnell's retirement raises issue: When is it time to ease up?