Surge in deadly Boise crashes spurs changes to protect bikers, walkers. What’s coming

It was a terrible phone call to receive.

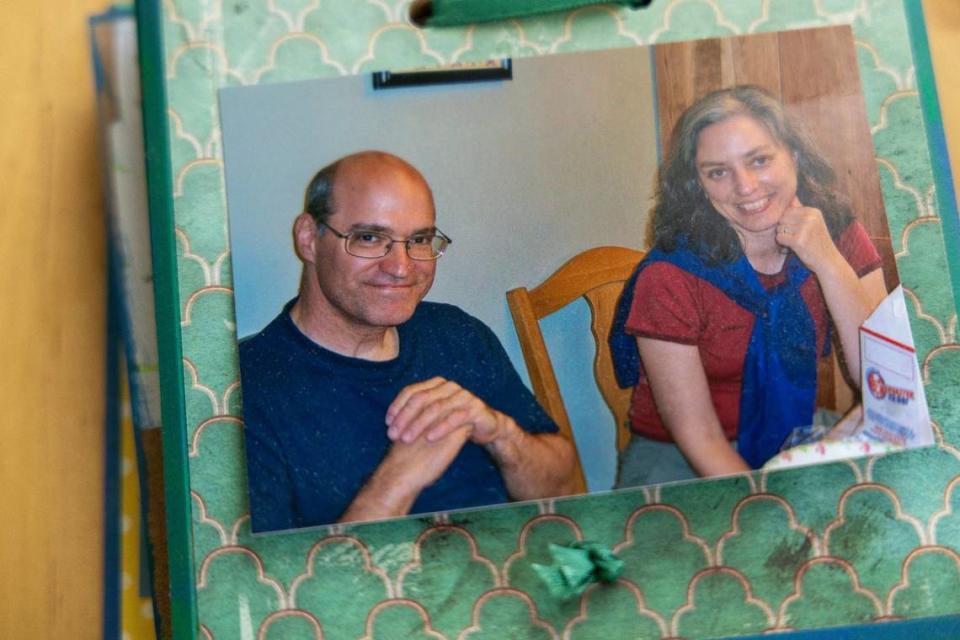

Early one morning in September 2010, Becky Dodge was settling in at work when she got a call from the Saint Alphonsus Trauma Center. Riding in a protected bike lane on his daily commute, her husband, Ross Dodge, was t-boned at the corner of McMillan Road and Leather Court by a driver rushing to turn left ahead of a school bus. Ross hit the car’s windshield, and his neck hit the driver’s-side rear-view mirror. He landed face-down on the pavement, still conscious but unable to move.

The nurse told her: “You need to drive very carefully on the way here,” Dodge recalled.

The crash left Ross an “incomplete quadriplegic,” which meant he still had sensation and was eventually able to walk again. But he suffered from “24/7 pain” that was difficult to manage without pain medication — which could have had fatal side effects because of his condition. He left the hospital after four months, Becky said, but the nerve damage that accompanied his spinal injury was a “lifetime sentence.”

Crashes like these have spiked nationwide in recent years, and the Boise area has not been spared. In response, advocates and city and county officials are trying to take a more proactive approach.

Through a Traffic Fatality Review Task Force, created in late 2023, they visit crash sites in person to assess what factors may have contributed, whether that’s a multilane road without a crosswalk or an intersection with a blind turn. They then look for other spots nearby that may have similar problems that can be fixed before there’s a crash.

The site visits are part of a constellation of other efforts, including the city’s Vision Zero Task Force, created in 2021, and an ongoing regional effort by Compass, Southwest Idaho’s community planning association, to put together a regional safety action plan for Ada and Canyon counties. Compass’ effort will allow it to create a crash data dashboard and a toolkit of countermeasures.

Advocates say today’s problems stem from the ways American roads, especially in suburban areas, were designed years ago.

“Most of our design philosophies in the past have been, ‘We want to move as much traffic as fast as possible,’ ” said Don Kostelec, a transportation planner who worked for the Ada County Highway District in the early 2000s. “That brings speed. (And) speed is what ultimately turns out to be the issue.”

So speed is what many local and regional agencies are now targeting. Traditionally, many cities have viewed traffic deaths as inevitable, focusing on enforcement and personal responsibility with a goal of minimizing collisions. But increasingly, the focus is shifting to engineering roads to allow for the possibility of a crash, but significantly reduce its seriousness.

Compass’ effort draws on the U.S. Department of Transportation’s adoption of a “safe system” approach, which deems deaths and serious injuries from crashes “unacceptable” but acknowledges that drivers’ fallibility makes the elimination of all crashes unrealistic. It’s an approach that has found success overseas, advocates say.

Even in its early phases, Compass’ effort has revealed some patterns, including the dangers of multilane roads and roads with speed limits above 35 mph. Some countermeasures will involve lowering speed limits or changing roads’ engineering to slow drivers down.

“We’re not trying to eliminate all crashes. We know that’s not feasible,” said Hunter Mulhall, a principal planner at Compass. “What we’re trying to do is minimize the consequences when these things do happen, so that they’re not life-altering or fatal incidents … It’s less about trying to control people’s behavior than about the outcomes when people do make mistakes.”

A ‘huge spike’ in traffic deaths and injuries

Evidence of the increase in traffic deaths and injuries is stark. In January, the Idaho Transportation Department reported a 20-year high in traffic deaths, with over 270 people killed statewide in 2023. Most were people in vehicles, but pedestrian and bicyclist deaths nearly doubled from 2022, the Idaho Statesman reported.

Ada County was not immune, with 31 traffic deaths in 2023, according to the Transportation Department’s report. There were 13 fatal crashes in Boise in the same time period, compared with five in 2022.

These numbers reflect a problem nationwide. A 2023 study by the Governors Highway Safety Association of 2022 data found that drivers struck and killed at least 7,508 people walking, the highest number nationally since 1981.

“We’ve seen national trends moving the wrong way,” Mulhall said.

The reasons for this spike are less clear. Boise City Council Member Jimmy Hallyburton, a longtime bike safety advocate and member of the city’s task forces focused on limiting crashes and reducing their severity, surmised that COVID-19 played a role.

During the pandemic, he said, there were fewer drivers on the roads, which may have prompted those remaining to drive faster and treat traffic laws a little more loosely, perhaps running more red lights and stop signs when they thought no one was coming.

Bre Brush, Mayor Lauren McLean’s transportation adviser, said the pandemic also brought with it an uptick in substance abuse, which has lingered since and contributed to crashes.

Kostelec attributed much of the issue, especially bicyclist and pedestrian deaths, to the area’s rapid growth, which means more cars intersecting with more people out on the streets. Boise, Salt Lake City, Phoenix — “All of these places are experiencing the same problems,” he said.

In 2021, an analysis by the Idaho Policy Institute of crashes in Boise from 2005 to 2020 found that around 40% of all crashes occurred on arterial roads, like Ustick Road and Cloverdale Road, while over half took place at intersections.

Advocates are quick to point out that the data available don’t always show the full picture, especially when it comes to bikers and pedestrians. When there’s no property damage — or at least, when police aren’t called — crashes may go unrecorded unless someone goes to the hospital, Kostelec said. After a minor crash, a biker or pedestrian might just walk away.

State transportation data codes crashes in part by noting whether a death occurred. But victims are only coded as deaths if they die within one month of the incident.

This quirk of the data was especially painful for Ross’ family. As time went on after his crash, “the pain would just increase,” Becky said. After 11 years, it became overwhelming, with no real end in sight, and Ross decided to go into hospice care. He died in December 2021 at 63.

The fact that Ross’ death was, in a sense, not counted, prompted his family to install a “ghost bike” at the site of the crash.

“What it makes us feel like is that Ross’ situation — crash — didn’t matter,” Becky said. “Not everyone dies, but that doesn’t mean they’re fine, either. I think we forget that.”

A ‘cross-disciplinary approach’ to prevent crashes

Compass’ safety plan will be relatively high-level, identifying patterns and trends across multiple roads in the area rather than at specific crash sites.

To complement that effort, Hallyburton started a Traffic Fatality Review Task Force late last year that visits crash sites in person. During one of its recent visits, the group walked along a section of Cloverdale Road with members of the Boise Police Department, deliberating whether it needed a crosswalk.

“While we were standing there, a gentleman comes out of the subdivision and starts to cross, and then he looks over and sees (police officers) and walks down a ways — but then proceeds to illegally cross just out of sight,” said Jill Youmans, a communications manager for the city. Visiting the site in person, she said, reinforced that it’s not “ ‘maybe we need a crosswalk.’ No, we need a crosswalk.”

The site visits involve representatives from the Boise Police Department, the Ada County Highway District (which controls most Boise streets) and sometimes local transit safety advocacy groups. In the past, these groups conducted their own analyses in response to a crash — deciding how better to enforce the law, for example, or deciding to repair a curb or add more protection to a bike lane.

Now, the groups are taking what Brush called a “cross-disciplinary approach.”

“Never before have we all been together saying, ‘OK, we saw this over here, and that might also happen over here,’ ” she said.

Becky Dodge welcomes the efforts. Years after her husband’s injury and death, she views his experience as an especially cruel irony.

He had spent much of his career working with Compass helping to plan safe bike routes. In his spare time, he taught kids in the community, including his own, how to ride their bikes safely. He was a collector: He had a tandem, a unicycle, “every kind of bike,” Dodge said. They had just become empty nesters when the crash happened, and the two of them were planning bike tours in their retirement.

“We were just on the cusp, ready to go,” she said.

To this day, Dodge struggles to watch news coverage of crashes, knowing from experience how many people will be hurt deeply by the loss.

“These statistics, there’s people behind them,” she said. “There’s not only the people behind the crashes, there’s the families. There’s the people who live across the country who might have been influenced by this person.”

“We all lose when anyone dies needlessly, or is hit and incapacitated needlessly,” she added. “It’s a complete waste.”

Idaho saw over 270 traffic deaths in 2023. It’s the highest number of deaths in decades

Ada County coroner identifies 6-year-old boy struck by a vehicle while riding his bicycle

Bicyclist struck by car in downtown Boise has ‘life-threatening injuries,’ police say