A tale of two tenants: B.C. renters feeling affordability squeeze as parties campaign on housing

The sound of jackhammers and excavators echo through Kim Gerelus' Burnaby apartment as construction crews tirelessly carve out the foundation for a new condo development next door.

One by one, the low rises on McKay avenue are being torn down in favour of modern condos and townhouses — and her building is next on the chopping block.

"It's unnerving. It's stressful," said Gerelus, 65, who has lived in her one bedroom apartment with her mother for three decades. "We don't want to leave our home. We don't want to have to leave Burnaby."

Like other residents in their building, the pair will be forced out once its demolished, and face significant rental increases.

"We're on a very fixed income, we have bills and all kinds things going on — and we just can't do it," she said.

Gerelus says she feels unrepresented in the federal election as the growing affordability crisis puts greater pressure on renters like her. It's a sentiment that's been echoed by housing advocates as rental rates across the region skyrocket.

How we got here

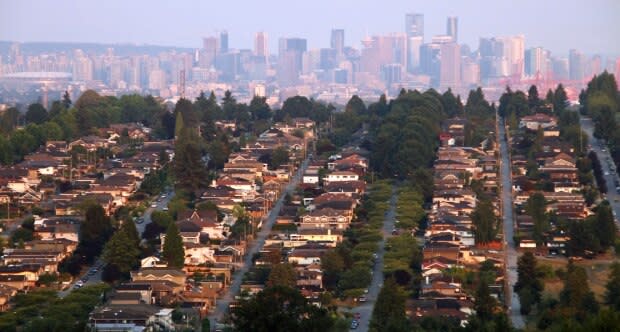

The Burnaby South riding where Gerelus lives is among the most expensive ridings for renters in all of Canada, according to the B.C. Non Profit Housing Association. Six Metro Vancouver ridings in total land on the list.

From foreign investment to money laundering to overall population growth, there are many factors playing into B.C.'s hot real estate market.

But Andy Yan, director of city policy at Simon Fraser University, traces the affordability gap back to the 1990s, when federal subsidies for non-market housing were effectively shut off.

"It really began with this belief that market system would provide the kind of housing that Canadians need," said Yan. "With the hindsight of 2019, we know that there are proportions of the population that market housing isn't going to meet that demand."

"This is really the accretive effect of decades of non-investment in non-market housing," said Yan.

The missing middle

Musician and local health worker Peter La Grand is among grappling with the swelling costs of living in Metro Vancouver. He and his wife are both working professionals, with three kids.

After renting in Vancouver for years, the family recently was accepted into a co-op — a victory he describes as like "winning the lottery."

But times are still tough.

"We sold our car a few months ago to try to make things simpler, so our costs are really food and rent. And even then … I give the image that the water is right here (below our heads). And we keep treading water, but we're not saving."

La Grand says he plans to vote, and hopes representatives make a push toward building more social and co-op housing.

Where the parties stand

Housing is a pillar of the major party platforms.

The Liberals plan to build 100,000 affordable living units, and renovate up to 300,000 already existing units as part of their national housing strategy. The dollars would be split with the provinces. Subsidies would also be made available to first time home buyers.

The NDP platform includes building 500,000 affordable living units, and the potential for a rental subsidy in the interim. As for how that money would be raised, representatives said the dollars would come from a one per cent tax increase on the rich. Money would also potentially be re-allocated once the party cuts off fossil fuel subsidies.

The Greens have pledged to build 25,000 homes each year for a decade. Representatives told CBC News that the party would also look at an increase to rental supplements.

The Conservative Party has promised to ease up the mortgage stress test to get more people into the housing market. A proposed universal tax break would also save Canadians hundreds of dollars per year.

The People's Party of Canada does not have a specific housing platform.

Housing advocates say pledges for widespread affordable units are encouraging, but a prolonged effort is needed to curb the 'rental crisis.'

"It took us 20 years to get here," said Thom Armstrong, executive director of the Co-op Housing Federation of B.C. "We're not going to get out of here in one electoral cycle or one budget. It's going to take a sustained, strategic investment in affordable housing supply — and then we'll start to make a dent in the problem."