'Theatre of strength': where the thin blue line meets the mental health crisis

On 15 September, a man brandishing a large kitchen knife was spotted inside a toilet in the Lilydale Marketplace. Armed with the knife, he made his way to a medical centre where he filled out a new patient form. The police were called to the busy shopping complex at 8.30am. First responders confronted the man outside the medical centre. He was asking the officers to kill him.

“We now have two more police vehicles,” a bystander told a live radio broadcast on 3AW. On mobile phone footage, the 24-year-old man appears agitated as he sparks a cigarette. The police had been negotiating with him for half an hour. They urged him to put down the weapon. The man rushed towards the police officers. “And we now have police in black,” the bystander continued. “Oh shit, they’re shooting. They’ve just shot. There’s just been three or four rounds. I can’t see.” Two officers fired their weapons and shot the man. Police believed the man, who remains in a stable condition, suffered from mental health issues.

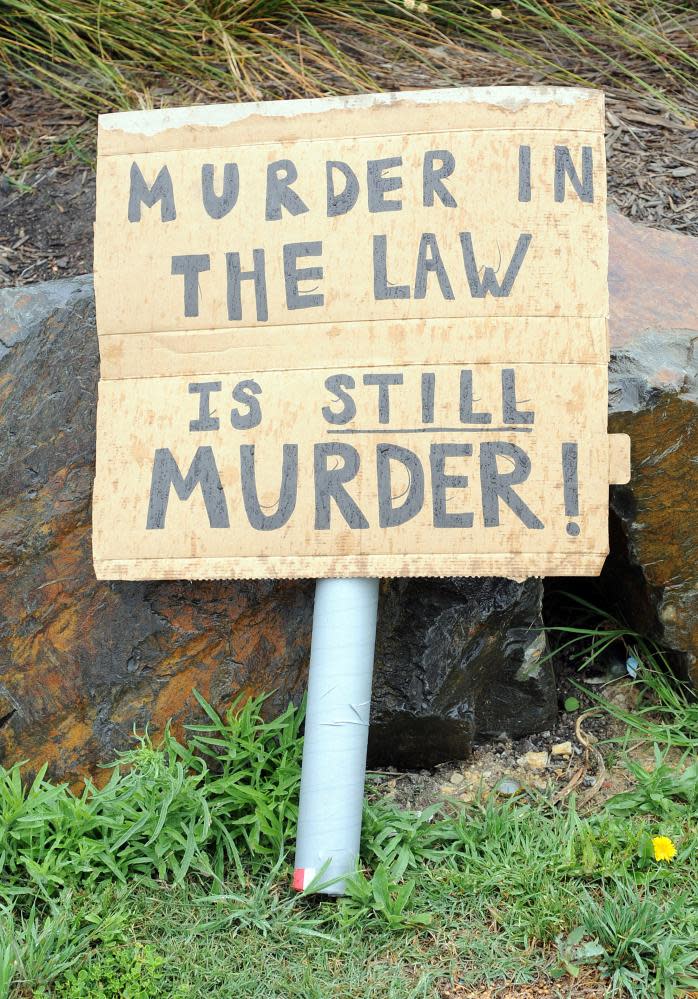

In recent months, Victoria police has been involved in a number of shootings and violent incidents that have again raised questions about training and processes regarding the use of force. Underpinning these incidents is a problem that has haunted Victoria police for over two decades; the excessive use of force against people suffering from mental illness.

This year there have been eight police shootings. Five involved people reported to be suffering from mental illness and involved varying degrees of threat to the public. Three of the shootings were fatal.

Related: 'Relax, you are OK', witness told a knife-wielding Melbourne man before police shot him

In March, a 34-year-old Roxburgh Park man was shot dead by police after he stabbed and killed three people. His mental health was flagged in Victoria police’s internal crimes database.

In June, Victoria police were called to reports of a 53-year-old man in distress pulled over on the Monash Freeway. The assistant commissioner, Robert Hill, gave an outdoor press briefing on the busy freeway, explaining: “We tried to negotiate with the male. We tried to actually calm the male down. At a point during that course in the negotiations the male has produced a knife and advanced on the police members.”

After a failed attempt to physically remove the man from the vehicle with non-lethal force from a bean bag round, two shots from a semi-automatic handgun were fired into his chest. “As a consequence, that man has died on the side of the road.” When asked about the distress, the assistant commissioner replied, “you could term it as a mental health episode”.

In July, 30-year-old Gabriel Messo was fatally shot by police after attacking his mother with a knife in a Gladstone Park reserve. The coroner’s inquest found that police had been aware of Messo’s battle with mental health since 2016. He suffered hallucinations and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

After the Lilydale shooting, the deputy commissioner, Neil Paterson, was clear in his message: “No police member comes to work expecting or wanting to engage in the use of force and particularly shoot someone … I understand, one of the police members involved is in their first few weeks after graduating from the academy.

“On this occasion we had a number of use of force options that are available to police. Certainly, one of our best use of force options is actually talking to a person and negotiating with them.”

Last week the Police Association of Victoria secretary, Wayne Gatt, told Nine’s Today show officers faced a mental health-related incident every 10 minutes in what he described as a “mental health crisis”. The system, he said, is broken.

‘Culture of heroism’

Throughout the late 80s, the Russell Street bombings of police headquarters, resulting in the death of 21-year-old constable Angela Taylor, and the Walsh Street police shootings, resulting in the death of 22-year-old constables Steven Tynan and 20-year-old Damian Eyre, contributed to an identity crisis within Victoria police. There was a growing sentiment among officers that they had slipped from guardians to targets, described by Victoria police, in a publication titled Project Beacon: Overview of Progress, as a “heightened sense of vulnerability”.

Paterson echoed the vulnerability sentiment in his press briefing. While responding to questions regarding the Lilydale Marketplace shooting, he referenced a spike in attempted gun-grabs and assaults directed towards Victoria police officers.

A 2005 review conducted by the Office of Police Integrity found that officers were retrained with an emphasis on controlling violent criminals. Misunderstanding of public expectations – that is, believing the public expects to be protected from violent crime quickly and forcefully – coupled with intensive firearms training were also considered contributing factors to the spike of police shootings throughout the 90s.

Between 1984 and 1995, Victoria police were responsible for more than 30 fatal shootings. The number was double the amount of fatal police shootings when compared to the combined number of every other state. The majority of the victims were suffering from mental illness and affected by drugs and alcohol. At the time, the attitude was described by the state coroner Hal Hallenstein as a culture of heroism where “worth is proved by accepting personal risk and displaying personal courage”. Officers sought to resolve an incident quickly and forcefully.

An internal Victoria police report, written by Superintendent Bruce Logie, claimed that the intensive firearm training was lacking defensive tactics and conflict resolution. An internal inquiry led by Task Force Victor took issue with training methods being based on a “presumption of rationality”.

Dr Richard Evans, a lecturer in criminology at Deakin University, believes this miscommunication is at the core of police engagements with people suffering from mental illness. He told Guardian Australia: “The police tend to operate on the assumption that the person that they’re dealing with is rational. If a police officer were to draw their firearm and instruct me to do anything, I would do it because it’s the rational thing to do. Someone who’s having a mental health crisis is not rational and they may not respond in a rational way.”

Also crucial is the apparent lack of understanding about how to deal with those suffering mental health. Shocking cases like that of John, a disability pensioner whose psychologist called triple-zero because she was worried about his deteriorating mental health, point to systemic failure. Within minutes of arriving at his home, six police officers were holding John down in his front yard and beating him, humiliating and traumatising him – and being filmed on John’s own CCTV.

Likewise the more recent case of a man reportedly with severe mental illness being knocked down by a police car before a policeman appears to stomp on his head while six officers surround the man on the ground. The man was taken to hospital and placed into an induced coma while civil rights groups called for greater scrutiny and transparency in the investigations process.

Chris Maylea is an academic with RMIT and chair of the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council, the peak Victorian advocacy organisation for people with a lived experience of mental health. He told Guardian Australia: “Many people who experience ill treatment or brutality at the hands of the police are just not believed. Often people’s experiences are just written off as a delusion. We’re seeing these incidents more and more because people have got their smartphones but they’ve been going on for decades.”

Dr Maylea believes the key to de-escalating situations with people suffering from mental illness is supportive care, understanding and compassion – not sirens, guns and handcuffs. A problem that is compounded by a lack of police consequences. “What we have currently in Ibac is clearly not working,” says Dr Maylea. “The days of police investigating police has to come to an end. There has to be a mechanism for really rigorous, transparent, independent investigation when these things occur.

“If somebody seeks help and they end up being brutalised or traumatised, they are much less likely to seek help again in the future. Their trust in the system is completely eroded by this kind of violence. And it’s not just that person, every other person who reads the news or watches TV and sees this kind of response goes, ‘I don’t think I’m going to seek mental health support, if that’s what’s going to happen to me’,” explains Dr Maylea. “In one recent case the person was seeking support from mental health services, was denied support and then police were called. The mental health system is failing to provide the support that people need when they need it. And then it’s left to police, who are completely inadequately prepared, to respond.”

****

Following a peak year in 1994, when nine people were killed, all Victorian police officers were to undergo a specialised training initiative called Project Beacon. The core objective was the preservation of life and a strategy that encouraged the use of minimum force through a considered diffusal strategy as opposed to a fast and forceful method. Although the new training technique was a vast improvement, a report by Springvale Monash Legal Service found that there was minimal training provided to frontline officers engaging with people suffering from mental illness.

Around this time, support for people with mental health issues was diminishing – between 1995 and 1998 psychiatric institutions went through a deinstitutionalisation process that meant the institutional mental health service system would be replaced with community-based services. The process was complicated by inadequate funding, which led to overcrowding of these programs. On the front line, this meant police would be left to manage a disproportionate share of the problem.

In the short term, Project Beacon successfully reduced the shooting incidents across Victoria. Until the first decade of the new century, when there was another upturn of civilians being fatally shot by Victoria police.

By 2005, in response to six fatal shootings over two years, the Office of Public Integrity asserted that the “safety first philosophy” of Project Beacon was fading and recommendations from the review were not implemented fast enough.

Then, once again, it took another tragedy to bring the issue of excessive force to the fore.

‘Training too often ignored’

In 2008, a 15-year-old boy named Tyler Cassidy was drunk in a suburban park. Cassidy had stolen two large kitchen knives from a shopping centre and threatened passersby, insisting they call the police. When police arrived, they asked Cassidy to drop the knives. The police officers used capsicum spray twice in a failed attempt to subdue the teenager. As he rushed towards the leading constable, he was fatally shot five times. The encounter lasted 73 seconds. His post-mortem blood alcohol reading was between 0.09 and 0.11.

At the inquest into Tyler Cassidy’s death, the state coroner Jennifer Coate reported that the risk assessment skills, specifically regarding instances where police were to deal with offenders with mental illness, had continued to decline up until 2008.

A second review was conducted by the Office of Public Integrity in 2009, in which the same recommendations from inquiries from the early 90s were recited: Victorian police officers were criticised for attempting to resolve incidents too quickly and were lacking the necessary skills to de-escalate volatile situations that involved people suffering mental illness.

Gregor Husper of the Police Accountability Project, a public interest legal project, told Guardian Australia: “These systemic issues arise from the number of unwarranted police contacts with people experiencing mental illness where there is no underlying offending. In many cases, these encounters are triggered for no better reasons than the person’s unusual behaviour has attracted police attention, in the absence of any reasonable belief of unlawful activity or threat of harm to others.”

“Too often police ignore any training about establishing rapport, and they fall back on perceived imperatives to maintain situational control and functional imperatives to enforce laws,” says Husper. “This can have distressing, catastrophic and fatal outcomes for people with mental illness.”

In 2012, another Office of Public Integrity review identified a commitment by Victoria police to improve their responses to people suffering from mental illness and emphasised “while it is important to learn lessons, it is incumbent on Victoria police to ensure that these lessons are remembered”.

The lessons and training modules administered over the years have been many: de-escalation training courses; role playing; scenario training; mandatory mental health awareness training for all frontline police; meeting people with lived experience of mental health issues to enhance better understanding.

New processes were implemented: From 2007 to 2011, around the time the fatal shooting of Tyler Cassidy occurred, Victoria police trialled the Police, Ambulance, Clinician Emergency Response (Pacer) program, a “co-responder” team that involved a mix of police and mental health clinicians to assess a mental health crisis in the community such as suicide or self-harm, family-violence and threatening or harmful behaviour.

Prior to the program, when officers were called to respond to an incident clearly involving mental health issues, they would call the “mental health triage”, where clinicians would offer advice and referral over the phone. With the Pacer program a clinician can physically attend the scene and transfer the patient to a mental health facility if need be.

However, Pacer units are not a 24-hour service – they generally operate from 2pm to 10pm, seven days a week.

Evans told Guardian Australia: “They (the police) are the only government service which is available 24-7 and actually responds when you call. There are crisis assessment teams, which the department of human services deploy, and there are various medical resources. But they aren’t available all the time and they can’t come straight away.”

“Police should not be the first people called when someone needs mental health support in the community,” a Police Association of Victoria spokesperson told Guardian Australia. “Health services should be, and these services need to be increased across the sector to provide appropriate support for people when they reach out for it.”

‘Backwards law’

Evans attributes the problem of mental health issues and policing to a principle in criminology called a backwards law. He says: “Put simply, the less likely a particular form of crime is, the more newsworthy it is. This leads to greater focus on the real but minute threat at the expense of the genuine crises in our community.”

“We are focusing our energy, effort, resources, our fears, our anxieties, our attention in the wrong direction.”

In 2017, following the Bourke Street massacre and in response to the growing threat of terrorist attacks, Victoria police replaced the de-escalation method of Project Beacon with a “casualty reduction” policy that clarified their right to use lethal force in early intervention.

In December 2017, the Age reported that all Victoria police officers were sent a memo calling on them to act like heroes. The message concluded: “In performing this role members may be required to perform tasks that may be considered inherently unsafe.”

A new $1.8m virtual reality training program was rolled out to tackle the headline incidents, such as terrorist scenarios and mass shootings. The policy shift meant all junior police would be trained to confront potential threats quickly and forcefully.

This reaction to public pressure is what Evans describes as a theatre of strength. “Victoria police know this and they try to do their job as well as they can. They do, however, feel obliged to react to public pressure … their job is to reassure the public,” Evans explains, before adding, “the core of what they do should be based on real information rather than heightened fears that may not be based in evidence.”

****

After the coronial inquest into the death of her 15-year-old son, Shani Cassidy told the Age: “… it distresses me greatly that on the night of his death Tyler was in crisis and clearly needed help. Instead he was shot dead,” she writes.

“I will always believe Tyler’s death was preventable … I hope that the coroner’s recommendations are quickly adopted and can help provide Victoria police and its officers with better conflict resolution skills so that another life is not lost.”

Another decade has passed.