Can therapy stop bullets? These trauma counselors think it might

EDITOR’S NOTE: This reporting is part of ongoing Charlotte Observer coverage about gun violence, its impact on families and communities and relevant public policy.

Twice a week at an abandoned school close to NoDa, children and teens gather in a small classroom littered with Rice Krispie treats, Connect-4 and a pile of yoga mats.

Here, the kids tell their “teacher,” a licensed counselor, about everything from art and basketball to anger issues.

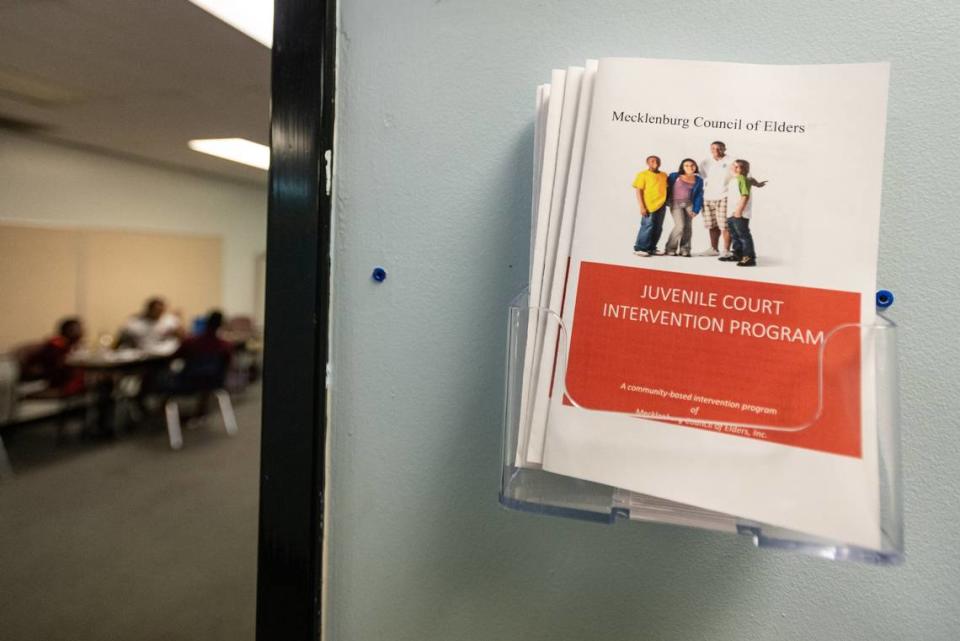

Volunteer counselors with Charlotte’s Council of Elders, a nonprofit made up of 15 grassroots organizations, are working with the children and teens to find the root of their trauma. Some children are exposed to traumatic experiences at school or in their neighborhoods, while others face adverse situations in the home.

The class is called Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). It is part of a larger Juvenile Court Intervention program aimed at helping youth stay out of the court system. The Mecklenburg County Council of Elders offers the counseling program combined with other classes on topics like career building and anger management.

Kids and guns have been the focus of the past two CMPD police chiefs, and remains a top priority for the department. In addition to becoming the victims of gun violence, children and teens are becoming the perpetrators. Police officials, in a July CMPD news release, said they are seeing children as young as 13 “armed and routinely committing shootings.”

Last year, six teens under 18 and as young as 14 were shot and killed in Charlotte. And, in the first half of 2022, 482 children under age 18 had been victims of gun violence, according to CMPD.

Police are often left reacting to gun violence, as is the court system, by arresting and sentencing youth offenders after a shooting happens. Counselors with Mecklenburg’s Council of Elders are taking a different approach. Instead of reacting to violence, counselors are trying to stop it before it begins by helping children and teens address their behaviors.

Lisa Hollis, one of the counselors, says she hopes to help the youth find alternatives to violence.

“A lot of them feel scared and so they do want to get a gun ... so they can protect either their mom or their household,” Hollis said. To help them find other ways to feel safe, she said they work through their specific problems and connect them to other resources and people who can help.

Can therapy stop bullets?

Hollis says gun violence keeps her awake at night, especially the violence committed against young Black men. Black men from age 14-34 experience the highest rates of gun homicide of any demographic, according to the Center for American Progress.

“I have three sons myself, so like, as they get older, they become more of a threat, people see them as a threat instead of cute little boys,” Hollis said.

Hollis talks to her boys about how to stay safe, and she believes that working through experiences and anger issues can help prevent youth from becoming involved in conflicts that may turn deadly.

On one particular Wednesday last August, The Charlotte Observer attended an ACEs class Hollis was teaching. Two young boys, one going into middle school in the fall, and one elementary student, discussed how they felt about the start of a new school year, how to manage anger as an emotion, and what it means to be a leader.

Hollis says having someone who cares helps the kids to become more open and to develop trust in adults.

“We do notice that a lot of them have similar situations like there’s a single parent household, there has been a death in the family, there has been someone who has been incarcerated, there has been some drug and gang violence,” Hollis said. “A lot of them cause anger issues, there’s trust issues. There’s a lot of shyness where they completely shut down as a result of being exposed to domestic violence, and they still work on them to get their voice back.”

Another counselor who teaches the class, Tysha Pressley, said a typical classroom period lasts about 30 minutes.

Often gun violence starts with the children experiencing trauma and not feeling safe. Then as they grow into their teens, they fall into a pattern of violence and unresolved anger issues and they carry guns because they don’t feel safe, said Pressley, a licensed clinical mental health counselor.

One of Pressley’s clients brought a gun to school and was sent to her, she said. She is working with him to help him understand why he brought the gun.

“When he took that gun to school, a lot of times it meant that he didn’t feel safe, because of what he experienced in his life,” she said.

Pressley said this kind of fear is common among the kids she is seeing.

“So what I’m seeing with kids ... is a general feeling of anxiety in regards to the particular kid’s neighborhood, feeling as if they are not safe,” Pressley said.

When kids aren’t able to feel safe, they sometimes turn to guns to protect themselves, she said.

“We have to look at the more systemic issue in regards to making our community safer,” Pressley said.

She said the community can help by making sure that parents have access to the resources and the support that they need in order for them to feel safe, so they can create safety for their children.

While the ACEs program aims to prevent gun violence, another initiative in Charlotte focuses on making sure that when a child or young person is shot, it doesn’t happen again.

Atrium Health Medical Director for the Violence Intervention Program Dr. David Jacobs said 1 in 4 victims of violence within Atrium’s network will become victims again. Often these repeat victims have lethal injuries and won’t return to the hospital, he said.

Britney Brown’s goal is to prevent victims of gunshot wounds from becoming victims again. Brown is the violence intervention coordinator for Atrium Health. She works inside the region’s only Level 1 trauma center, the only hospital in Charlotte equipped to handle youth with serious gunshot injuries.

The youngest patient Brown’s team has seen this year was a 10-year-old.

The program targets those who are under the age of 25 and most of the patients Brown’s team has seen are between 16 and 18.

The No. 1 commonality Brown sees is that most of those who were shot were engaged in interpersonal conflict.

“It is just interpersonal, coming from social media … it’s small arguments, and individuals find themselves feeling very threatened,” Brown said.

The violence intervention program hopes to connect patients with resources as soon as possible. And they hope to take a holistic approach to care by connecting with family, friends and the patient’s dreams.

Brown says the program’s main goal is to be a united front and prevent people from coming back to the hospital.