Think Canadians all speak the same? Think again

A new survey has revealed the subtle but very real linguistic diversity of Canada’s English-speaking population.

The data news site, The 10 and 3, recently surveyed thousands across the country to map differences in the differing words Canadians use in their daily lives. The results showed that Canadian English isn’t uniform and that in some cases people have made up their own words.

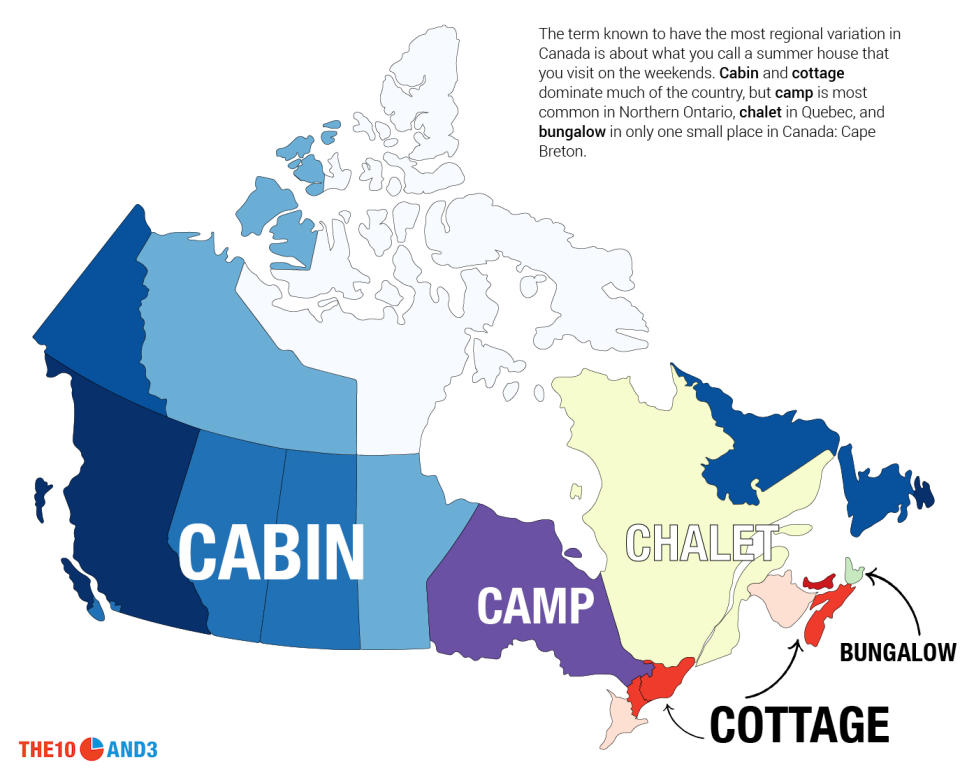

The maps highlight the unique words used by sub-regions in Canada, with special attention given to linguistically unique areas of the country like northern and southwestern Ontario, the Ottawa Valley, the Greater Toronto Area, the greater Vancouver and Victoria regions, Quebec, Cape Breton Island and Avalon Peninsula on the island of Labrador.

Canadians seem most regionally divided over what to call their summer homes out in the country. In western Canada, Canadians predominantly use the word cabin, although it can be seen decreasing in popularity the farther east one goes, with Newfoundland and Labrador being the only areas in the east to use the word. Northern Ontarions say camp while their southern counterparts and Maritime cousins both say cottage. Cape Breton sticks out as the one place in the country to use the word “bungalow.” Anglophone Quebecers use “chalet”, not surprising given the dominance of French in the province.

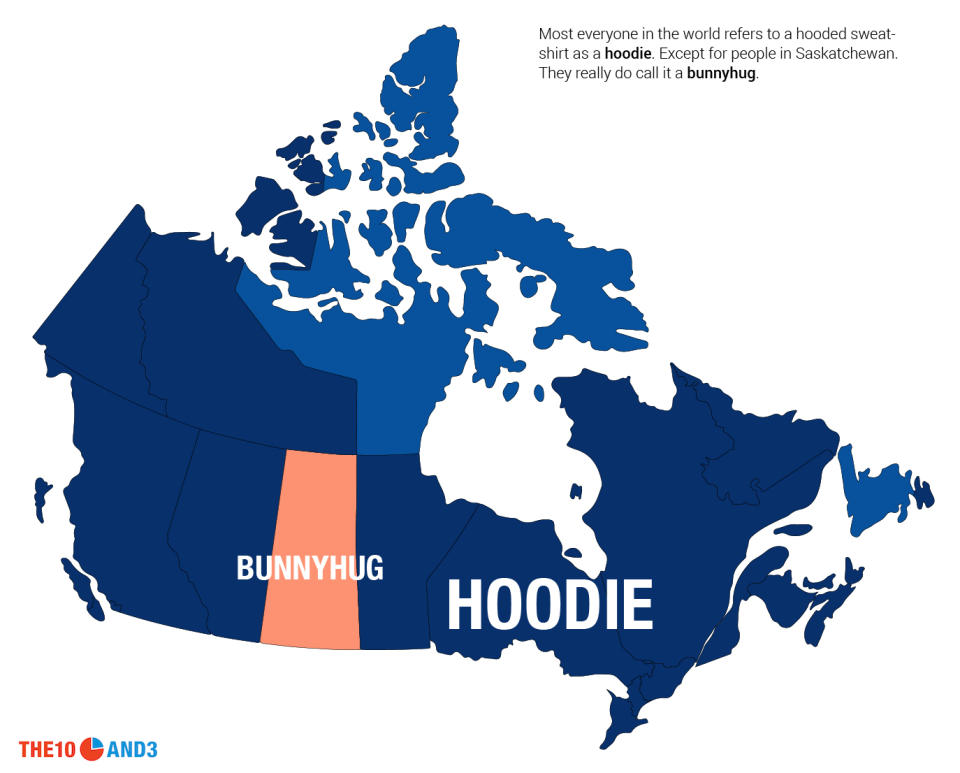

In a country that has winters as long as Canada does, warm clothing like hoodies are important. It’s also the one word that pits one province against the rest of the country. While the rest of the country says “hoodie”, the fine people of Saskatchewan opt for “bunnyhug”, a term that mystifies anyone not from the province. A 2007 article in the StarPhoenix suggests that the term came about in the 1950s, drawing inspiration from a popular dance move called the Bunny Hop. For whatever reason, the term took off in the province and has remained a staple word ever since.

Canadians are also divided on what to call exercise footwear. B.C. and the Prairies all went with runners, while Ontario and Quebec use the term running shoes. The Maritimes predominantly refers to the shoes as sneakers.

Canadians have also decided that there’s more than one word for kickball. While that staple of high school sports classes is called kickball almost everywhere its played, eastern Canadians prefer the mouthful “soccer baseball”. Western Canadians seem to have decided that “kickball” explained the concept of the game well enough.

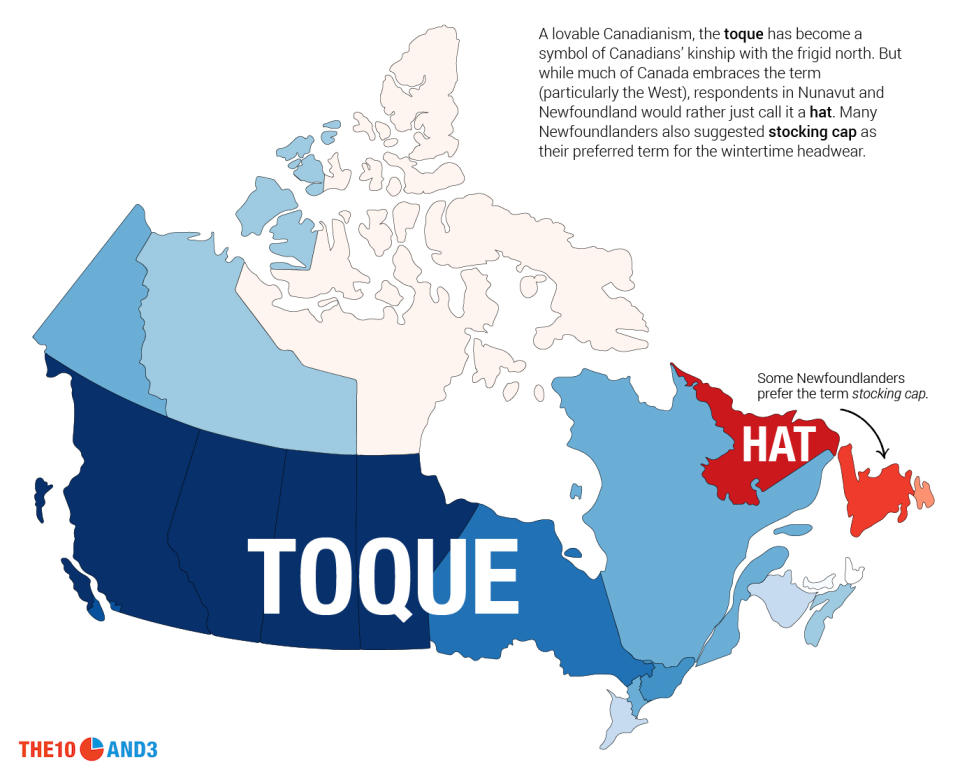

Like Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador found themselves virtually alone in forgoing the classic Canada term for a winter cap, “toque”. Instead they used the word hat, or stocking cap even, to the classically Canadian term that appears to be more loved in the western provinces more than anywhere else in the country.

While the reasons for Canadians’ curious linguistic preferences wasn’t explored in the survey, the maps reveal that there’s far more variety in Canadian English than is commonly assumed. The differences could be the result of different immigration waves, economic connections with different parts of the United States and Europe or myriad other factors. Whatever the reasons, Canadians’ English is full of interesting quirks.