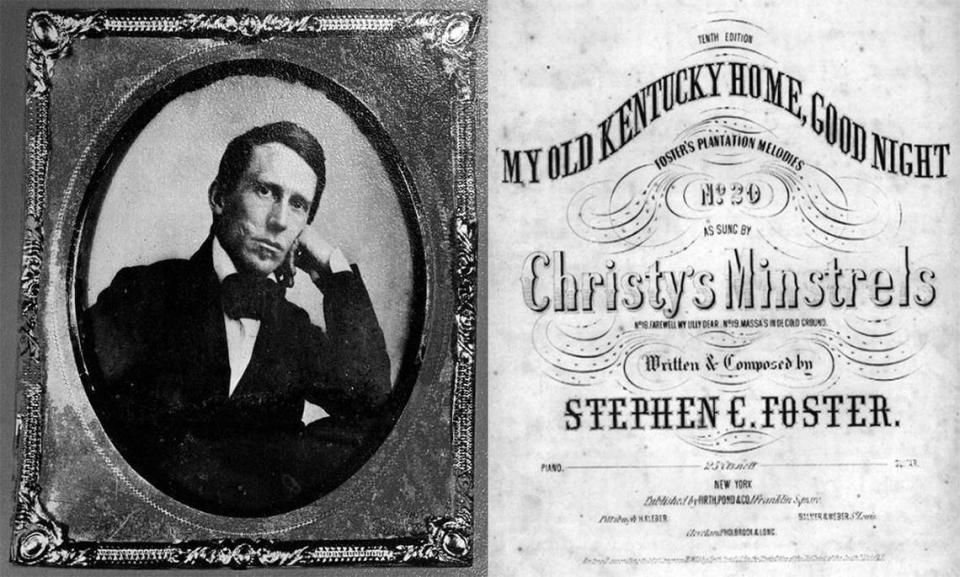

Time to dump pro-slavery anthem ‘My Old Kentucky Home.’ Here’s a ‘beautiful’ alternative. | Opinion

My Old Kentucky home

We are more than Derby and horses and bourbon

Plain, outdated, old times that have left many feeling stuck and depressed

We are more than nostalgia reminiscent of a time where some sipped

Disappointment over chilled ice — excerpted from “Home” by Hannah Drake and Kentucky students

In the pandemic spring of 2020, with most of the state shuttered, musician Ben Sollee sat alone in Churchill’s Downs infield with his signature cello and played “My Old Kentucky Home.”

The subsequent advertisement for Woodford Reserve bourbon — filmed with shots of the empty stands and racetrack as Sollee sang the plaintive melody — reverberated with the strange isolation we all felt during that time.

Sollee — a Lexington native who now lives in Louisville — had recorded the song before, and knew of its problematic original lyrics about an enslaved man being sold down the river, but went ahead with the video. But as summer continued and the protests over Breonna Taylor continue to rock downtown Louisville, and as Sollee talked to protesters and activists, his outlook changed.

The Woodford ad “really did tug on people’s heartstrings about being together, which is testimony to the power of the melody and the harmonic content of the song,” Sollee said in a recent interview. “But sadly you just can’t separate the music from the words that have been sung for nearly 100 years during the time it’s been endorsed as the state song.”

After some “real and honest” conversations with Black peers and musical collaborators “about how that song does not represent them or create a sense of togetherness,” Sollee decided to take it out of his repertoire.

Our roots are here, the bluegrass and banjo are as familiar as the beat of the drums

Our ancestors tilled the land, you see we are Kentucky too.

At times we have felt upset and unsafe...Home should be peace

Historic reckoning

Around the same time, author Emily Bingham, also of Louisville, published “My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song,” , a groundbreaking history about how the song not only glossed over the image of slavery in Kentucky, but was later shamelessly used in later economic development drives to create the facade of a more “Southern” state.

The book’s publication provided a moment of synchronicity, not just for Sollee but for David Thurmond, the executive director of Kentucky to the World, a non-profit that showcases Kentucky artists and intellectuals to send a different message out about the state. He wanted to use the book as a centerpiece of an entire artistic event. To that end, he recruited Bingham, Sollee and Louisville jazz pianist Harry Pickens. But his group also included large groups of high school students. They asked them to respond with one word to each of the following questions: What do you think about when you hear the word Kentucky? When you hear “My Old Kentucky Home?” What do you think when you imagine the future of Kentucky?

Enter Hannah Drake, Louisville poet and the creator of the (Un)Known Project on the banks of the Ohio River, which is a repository for the names of the enslaved across Kentucky. When she heard about the project, she offered to take the words, some 250 of them, and write a poem, aptly titled “Home.”

“She managed to create something very meaningful and very positive about Kentucky, using all of those words, even some of them that were not so positive themselves,” Thurmond said. “So Hannah presented a love poem for Kentucky.”

Last fall, she read the poem at an event in which Sollee and Pickens played an accompanying soundtrack.

But in isolation, we felt stuck, as our families were sold down the river to an unfamiliar place

The blue waters washing them away

We watched them drift into a land of nothing

We never got a chance to say goodbye

We prayed that one day if lucky, we would see them again.

What now?

Drake said the students provided her with a rich palette of words to create from.

“I wanted to tell the story and then lead to this element of hope and what young people wanted Kentucky to be, and it was all there,” she said. “In the end they want a Kentucky that’s about justice, equity and a place to feel welcome, and visible ... a state song should make you so proud of your state, not bring up imagery of enslavement.”

So could Drake’s poem with the help of Sollee and Pickens become an alternative state song or annual sing-along at Churchill Downs on Derby Day? Not any time soon. Officials told WAVE-3 recently that they had done a “survey” and people want it to stay, a statement that enrages Drake.

“Churchill Downs has a lot of power, so why not stand up and take the lead on this?” she said. “What will that hurt you to do that as an organization? We are no longer going to play this song because it’s about an enslaved person being sold down south? Why not be on the right side of history?”

At least people could start thinking about it, said Thurmond. “The hope will be enough people will hear and listen and think critically, that there will be a swell of enthusiasm about creating something that all Kentuckians could stand up and proudly sing,” he said.

Bingham thinks it’s time for the song to be retired. Many people in Kentucky and elsewhere are seduced by the melody, but don’t know the history or context.

“Now people are talking about the controversial song, learning how in the 1920s Kentucky leaders adopted an 1850s blackface minstrel hit about slavery as a brand—and as a celebratory, nostalgic, and patriotic anthem,” she said. “That was a different time. Jim Crow was the law and practice of the land. There is nothing to celebrate about slavery, but there is a lot to celebrate about Kentucky.”

Sollee would like to see some kind of petition started to retire “My Old Kentucky Home,” as the state song and Kentucky Derby standard.

“I think these words can and should and hopefully will prompt people to write their own anthems and state songs and over time something beautiful will come from that if we’re willing to make it happen,” he said. “I think that in my lifetime I will see a shifting identity in Kentucky that is more grounded in our natural landscape than our social history, and I think there will be some beautiful music written from that that I hope legislators and citizens will lift it up in song.”

Our greatest failure would be refusing to notice the ebb of the tides

We are a community that must embrace change

We can turn our chaos to calm

We can be a Kentucky where everyone feels a sense of dignity

Proud to say that they are Kentucky too

To read the entire poem, click here.