A tiny fraction of the high seas are protected. Why a UN treaty is needed now more than ever

Two weeks of negotiations at the United Nations headquarters in New York City have failed to produce a legally binding agreement to conserve and protect marine biodiversity on the high seas, despite urgent pleas to protect one of the last wild places on the planet from the pressures of climate change, overfishing, shipping and resource harvesting.

Many hoped the latest round of negotiations would finally produce a UN high seas biodiversity treaty for areas beyond national jurisdiction, also known as BBNJ. The international agreement has been in the works for more than a decade.

"We are closer than we have ever been at any time in this process to the finish line," Rena Lee, president of the Intergovernmental Conference on BBNJ, said during a brief address from the UN.

Talks will continue at a future date, which has yet to be determined.

Only about 1% of high seas are protected

While international waters represent two-thirds of the world's oceans — and 95 per cent of habitable space on the planet — only about one per cent are protected.

"More and more studies have been showing that marine species have been rapidly going extinct and we need to take a bold action," said Jihyun Lee, a youth ambassador on the High Seas Alliance, made up of more than 40 NGOs seeking to conserve the high seas.

"We don't have any time to waste," she said during a press briefing at the UN on Wednesday.

Daniel Wagner, chief scientist of the Ocean Exploration Trust, agrees. He's observed past BBNJ negotiations and said it's critical that nations agree to an overarching treaty enforcing sustainable use of international waters.

"This is an area that for a long time has been a little bit of a Wild West," Wagner said in an interview with CBC News from Honolulu.

"It's not like there are no absolutely no rules, but there's really a piecemeal and fragmented approach at the moment. We need to bring all of this together and have a holistic way of managing our ocean."

WATCH | Scientists aboard the EV Nautilus encounter sperm whale:

On expeditions aboard the EV Nautilus, a research vessel owned by the Ocean Exploration Trust, Wagner and his fellow scientists study unexplored parts of the ocean and share their discoveries via online live streams to raise awareness.

"When most people think about the high seas, the only image they would think [about] is maybe what you see when you look out of an airplane window — this vast expanse of nothingness and emptiness," he said.

"But when you get to be fortunate, like myself and others ... if you look in the right places, there are some really extraordinary things out there."

From deep-sea corals to ecosystems built around hydrothermal vents, Wagner says there's a remarkable wilderness to be discovered.

"We don't really know what's there. We don't really know the connections of many things," he said.

Deep-sea mining: solution or threat?

Without a treaty, many fear that international waters will be exploited for their resources before scientists can study the life there — and understand the potential impacts of human encroachment.

Already, as energy transition creates a hunger for precious metals to build batteries, companies are eyeing the ocean floor as a resource to harvest.

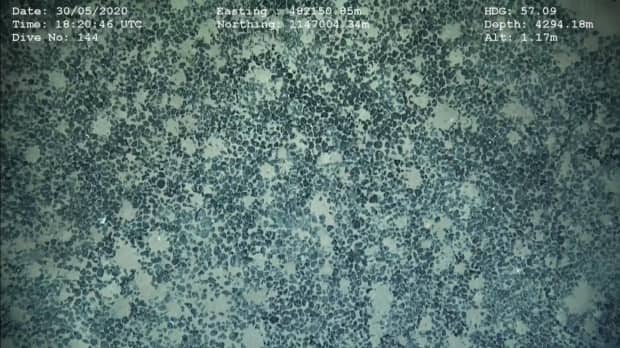

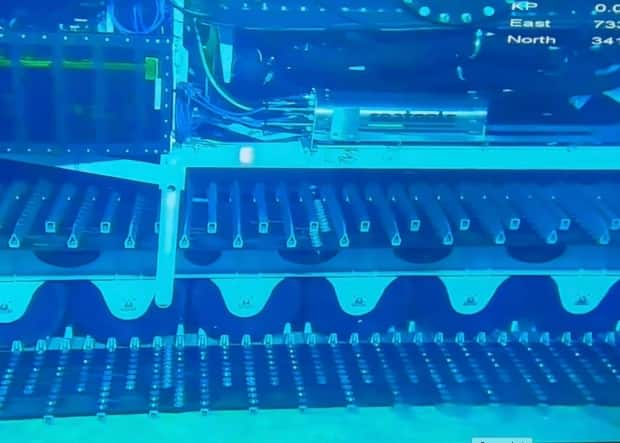

That includes a Vancouver-based mining startup called The Metals Company, which hopes to start mining polymetallic nodules by 2024.

It is one of 18 companies that has received a contract for mining exploration in what's called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), the seabed in international waters off the coast of the Pacific island nation of Nauru, northeast of Australia.

The Metals Company CEO Gerard Barron told CBC News that he believes land-based mining won't be able to fill the world's needs and that deep-sea mining is the answer.

"When you start adding up the metal intensity of moving away from fossil fuels, we don't have a choice of just doing one or the other. We have to make land-based mining more efficient, but we also have to explore new frontiers," Barron said.

The concept behind seabed mining, which is in the exploratory phase of development, is to gather mineral deposits from the ocean floor using a variety of deep-sea technologies. There are three key deposits of interest: polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulfides and cobalt crusts.

Seabed is more than a desert

Proponents of the industry say it's a lower-impact alternative to land-based mining that can provide the minerals needed to build more electric vehicles.

"Of course, things have an impact. The notion that we can have no impacts, that's a fairy tale," Barron said. "The question is, what will be the impacts and how can we mitigate those impacts? And then how do those set of impacts compare to what is happening today?"

When asked what his company's study of biodiversity in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone has revealed, Barron said that about 80 per cent of organisms in that area are bacteria, while the rest are mostly various sea worms, sea stars and some fish that "move away when we travel past them."

"I could play you videos of thousands of hours of sea-floor footage that we have and you just don't see much."

But environmentalists and scientists warn against oversimplifying the impacts of sea-floor mining by looking at only one aspect of an ocean's interconnected web of life.

"Even though our eyes don't pick up these tiny creatures, they are massive in importance in terms of carbon cycling, oxygen cycles and how nutrients move around," Wagner said.

Catherine Coumans, research co-ordinator for MiningWatch Canada, said the sea floor of the high seas is hardly an underwater desert.

"If you strip mine the seabed for minerals and metals, and destroy the biodiversity that exists there, that will have impacts and effects on all of the biodiversity in the water column above the seabed," she said in an interview from Ottawa.

"It's almost like having a tropical forest and saying, 'We're just going to remove all the soil and all the microbes, micro-organisms and everything that's in the soil, and somehow the rest of the forest is going to be fine.'"

Safeguarding that ecosystem is why, Coumans said, a UN high seas treaty is desperately needed.

Looking at the ocean holistically

Currently it's the duty of the International Seabed Authority to govern mineral-related activities in the international seabed and ensure protection of the marine environment.

But there are concerns that big-picture impacts of deep-sea mining in the ocean won't be prioritized without a high seas treaty because of the disjointed way that international waters are governed.

WATCH | EV Nautilus explores biodiversity on never-before-surveyed seamount:

"Right now it's kind of the right hand and the left hand pretending like it's two separate things — you know, 'our jurisdiction is the water column and your jurisdiction is the seabed' — as though those things are not intimately connected," Coumans said.

The bottom line, Wagner said, is that scientists simply don't know enough yet to say whether deep-sea mining can be done responsibly.

"We've only mapped about 20 per cent of the sea floor to a decent resolution. We've only laid eyes on a fraction of a per cent of the sea floor. So we don't really know what's there. We don't really know the connections of many things."

That's why Wagner and others say the priority should be to invest in the study and understanding of the high seas — and agree on a treaty that specifies mechanisms and processes to conserve biodiversity in international waters.