Take a trip to the N.B. mountain where the raptors soar

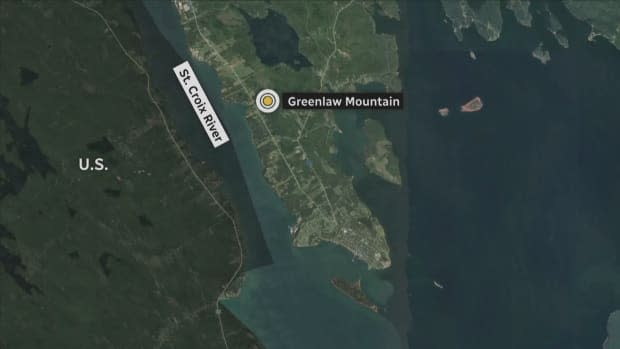

Getting to the top of Greenlaw Mountain, just north of Saint Andrews, N.B., isn't easy.

The road to the summit isn't exactly the dictionary definition of a road.

The gravel single lane winds its way through thick woods, with several steep sections to test the four-wheel drive vehicle, and deep washouts that force the driver to use every inch of the narrow road to avoid the holes.

Once you reach the cell tower at the top, a short walk north through the woods brings you into a clearing, which presents a spectacular view of the St. Croix River valley.

But the people who spend their days here through much of the late summer and early fall are more interested in what they see when they look up.

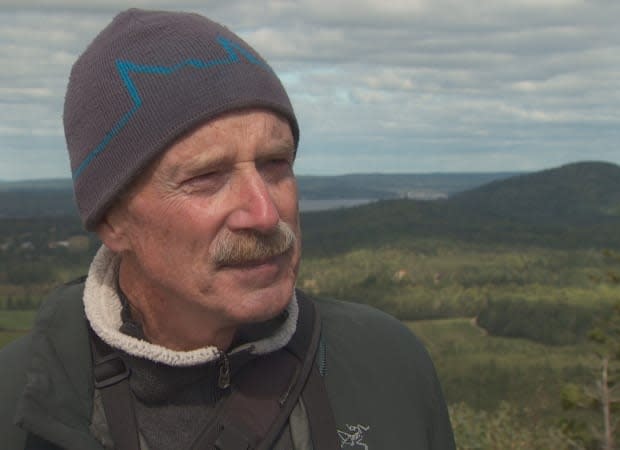

Todd Watts is the official counter of Hawk Watch, a program that gathers data on the migration numbers of hawks and other raptors.

Watts went looking for a good place to do that in 2008, after moving to the area from the U.S..

"It was a targeted effort, so I was looking for a naturally occurring concentration point for these birds of prey," Watts said.

"And I came up here after checking a bunch of other local places, and this turned out to be the best spot around — one of the best places in Atlantic Canada."

WATCH | Learn how expert eyes can track a raptor:

Watts said raptors are difficult to observe in their natural habitat, so the regular methods of counting birds aren't effective.

"With other species of birds you can conduct breeding bird surveys. You can go out in the forest or in the field where they breed and conduct a survey and get a good estimate of the number of birds that are there," he said.

"But, birds of prey, you can't do that. They don't announce their territory by calling, by singing, like many other birds and their nests are extremely difficult to find in the forest. So really the only way to document population status of birds of prey is to count them in migration."

An ideal location

Greenlaw Mountain isn't open to the public. It sits on private land, accessed by a private road.

CBC has been invited here by the Saint John Naturalist Club, which runs the program.

Hank Scarth, the volunteer chair of Hawk Watch, said Greenlaw Mountain is a perfect geographical location for observing the migration.

"It's sort of at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy before you hit the Maine-U.S. land mass. So the birds are migrating down the coast and they don't want to go over the water and this particular site is right on that line," Scarth said.

Watts and his team of a few dozen volunteers will be here into the month of November, whenever weather conditions are right, working from a small wooden platform.

This part of September is prime time for migration, especially broad-winged hawks.

Despite having cooler temperatures and north winds 15 — two of the conditions the birds like for migrating south — there are few sightings this day.

Heavy winds affect migration

Watts suspects the wind gusts, which are 80 kilometres per hour, are to blame.

"The stronger winds tend to keep the birds down, especially the smaller birds. They don't weigh as much, so they get thrown around by these heavy winds," Watts said

"And it becomes really inefficient for them to travel. They want to travel when they can burn the fewest calories. And heavy wind conditions [are] just not right for that."

Despite that, a tiny American kestrel, the smallest falcon on the continent, appears not far above the trees, and quickly glides off toward Maine.

Soon after, two bald eagles come into view, high in the sky.

They circle over the mountain, gaining altitude, before also heading into the St. Croix River valley.

A pair of turkey vultures catch the volunteers' attention, but because they show no signs of leaving the area, Watts treats them as local birds and doesn't include them in the migration counts.

Volunteer effort is critical

The weather can hold up migration for days, until a sudden shift comes and opens a floodgate of raptors that have been waiting to take flight.

That's when Watts can use all the volunteer help he can get.

"They could be anywhere in the sky and at various altitudes from just above sea level to a kilometre or two high," Watts said.

"Best day we ever had was last year on the 14th of September. We had a little over 5,000 individual hawks pass this point that we saw — those are the birds that we saw — there were probably others that we didn't manage to actually observe."

On busy days, Scarth said 20 or more volunteers will be on site to help.

"That's where our official counter really needs the help, just getting eyes on the birds and then he can deal with the identification because the identification of these hawks at a distance is really something that takes a lot of experience and work."

Watts also enlists the help of the black-capped chickadees that live on Greenlaw Mountain.

He has a feeder filled with seed at the edge of the woods to keep the chickadees close.

"The chickadees, when they see a bird of prey, they'll give off a warning call and that alerts me to the presence of the bird of prey. So I know to look up."

In 14 years, the group has seen species like the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon make a comeback, but some smaller species, like the American kestrel, haven't been doing as well.

Watts suspects a connection with a decline in songbirds and insects, both prey of the little birds.

The migration season of 2021 was a record year for the program, sighting more than 9,000 birds of prey from September to November, made up of 17 different species.

They likely come from across the Maritimes and the Gaspé.

Scarth said all the data gathered goes into a massive database managed by the Hawk Migration Association of North America.

"That's about 300 sites of hawk watches across North America, into Mexico even, and that data is then consolidated there and it's available without charge to science research, to public groups, to individuals," he said.

Since Greenlaw Mountain is the only regularly monitored hawk watch in the Maritime provinces, it is adding important information that otherwise wouldn't be available.

"If you love and respect something, you want to look after it," Scarth said.

"It's one small way that I and certainly members of the Saint John Naturalist Club can help out in support of conservation… you know, it provides that reward that you're doing something, small as it might be."