U.S. 'opportunity zones' use tax breaks for developers to help poor neighbourhoods — but are they really helping?

By most accounts, Beaverton, part of Oregon’s Sunset Corridor, is a desirable American suburb. It’s 15 minutes from downtown Portland, home to Nike headquarters and has a median household income of around US$50,000 range.

Why, then, are American taxpayers subsidizing developers to build in Beaverton, along with dozens of other economically robust communities just like it?

The answer lies in an ambitious public-private partnership initiative known as opportunity zones. Embedded in the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, aimed at incentivizing private investors to develop real estate in low-income communities and spur local business growth, the program has attracted billions of dollars in projects from Beaverton to Boston.

It enjoyed bipartisan support in the United States in the past and deserves broad attention now in the form of greater oversight and increased transparency. For Canadian businesses, opportunity zones would present both an investment opportunity and a model for economic development and are therefore worth watching.

But are opportunity zones accomplishing their economic goals in the U.S.? Can they do better three years into the program?

Campaign issue

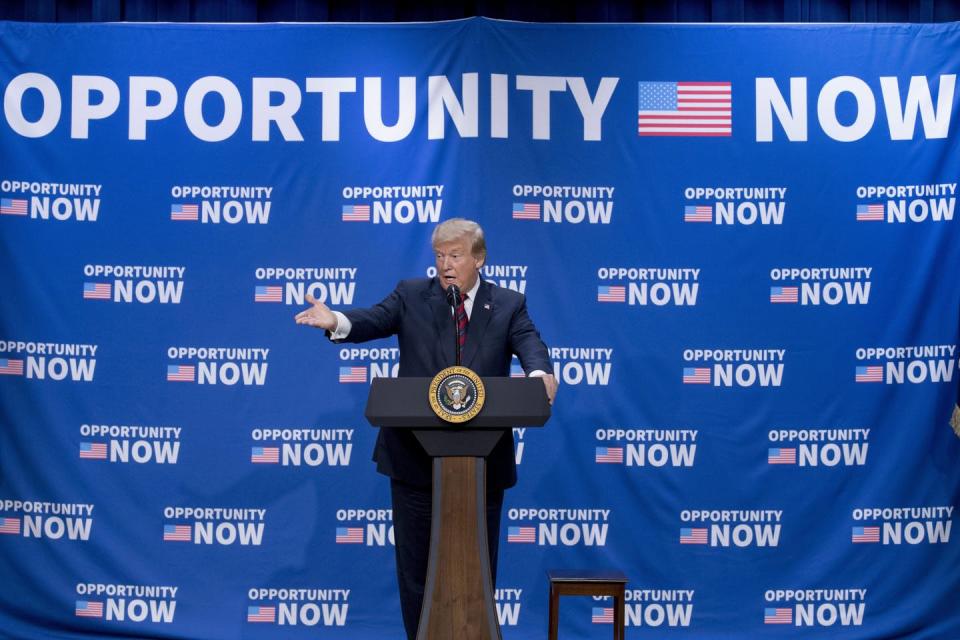

In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, opportunity zones became a divisive campaign issue because of concerns they weren’t helping low-income communities but instead neighbourhoods that were already rapidly gentrifying. Many on the left suggested they be eliminated while the right trumpeted their success. Joe Biden promised to reform the program if elected president.

Data from a new comprehensive study we conducted underscores that even though the program has needlessly enriched developers, it’s worth saving. In short, we see the potential for opportunity zones to fuel real growth due to their economic impact on local communities.

The opportunity zone program is well-intentioned — investors earn benefits by reducing capital gains taxes via buying and improving commercial real estate developments that support local businesses. The longer they stay invested, the more benefit they earn until the program ends in 2026.

So where did things go awry?

Let’s go back to Beaverton. While the 2010 U.S. census technically characterized the community as struggling economically, it’s seen an impressive turnaround since 2012. There have been significant year-over-year improvements in the unemployment rate and median household income. Yet, because of the low-income community designation, it qualified for a program that was designed to help communities in much worse shape.

Most opportunity zone projects have been clustered in communities like Beaverton – neighbourhoods that might not be affluent, but are far from low-income. In fact, many opportunity zone developments are luxury apartments that would have been built with or without tax incentives.

A search through our data turned up new luxury apartment buildings built in opportunity zones — a US$186 million development in Oregon, a US$254 million development in Virginia and a US$68 million development in Brooklyn, N.Y. We note that under current reporting guidelines, we are unable to determine which of these properties is taking advantage of the opportunity zone program.

Low-income areas left out in the cold

Our study analyzed a massive dataset of 36 million residential transactions. We found that the low-income areas identified by the census that were selected for the program tended to be more economically stable compared to tracts that weren’t selected, effectively snubbing the low-income communities that need government help the most.

We also found that while the residential price per square foot in opportunity zones increased by four to six per cent due to the program, the overall investment in these areas has not changed pre- versus post-designation. Our research reveals that much of the local price increases are not due to actual business growth, but are instead driven by high-end speculation.

The takeaway? Opportunity zones can positively impact real estate development and can help local communities. But to fully realize the program’s potential, we recommend U.S. policy-makers implement structural changes that are consistent with the original program’s intent.

First, there should be a greater level of transparency. A critical way to strengthen the program would be to provide visibility into investment activity, including public reporting of all properties purchased by opportunity zone funds.

Given the projected US$1.6 billion cost of the program, it’s in the American public’s best interest to measure the program’s impact on local communities. It would be particularly useful to have real estate transactions from areas of the country participating in the program — but are in “non-disclosure” states that restrict releasing real estate sales price data to the public — so that there’s a full accounting.

Second, since many of the selected tracts were already economically stronger than qualified non-selected tracts, we suggest evaluating existing zones using updated demographics data to focus on current low-income communities and potentially considering economic factors related to the real estate market.

Designating new zones and undesignating others would better target the communities that need the support of the program the most. In short, the designation can be dynamic.

Finally, we suggest additional conditions on the type of commercial development that qualifies for the program. Developers shouldn’t receive tax benefits to invest in luxury properties located in supposedly low-income neighborhoods. Instead, incentives should be targeted directly to local community needs.

Tightening requirements

The Opportunity Zone Reporting and Reform Act introduced in 2019 already incorporates some of these recommendations. It requires the government to collect and report on the program’s effectiveness annually, tightens the requirements to qualify as an opportunity zone and restricts high-end developments that don’t help local communities.

It’s a good start. We recommend pairing it with more transparency and publicly available data, and re-evaluating the current zones using additional criteria.

Finding neighbourhoods that can benefit from the program isn’t difficult. There’s a qualified but not selected area that’s only a 10-minute drive from Beaverton, for example. It’s home to 5,000 residents with a median income of around US$35,000 and a third of the residents are living below the poverty line. All they’re looking for is an opportunity.

John Maiden, former Head of Machine Learning at Cherre, a real estate data firm, and Ron Bekkerman, CTO at Cherre, co-authored this piece.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Maxime Cohen, McGill University and Dmitry Mitrofanov, Boston College.

Read more:

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.