Under the baobab: American dream is embodied in the spirit, aspirations of recent immigrants

Happy New Year, sisters and brothers, and Heri za Kwanzaa for Imani (faith) the last day of the seven-day feast of Kwanzaa. These principles remind us that even in trying times we must maintain hope in the ultimate triumph of the good in the human spirit.

Recently I was at a dolphin show where 2,000-3,000 audience members, mostly children, were awed and thrilled by the performances of our fish finned cousins. Shouting with glee, they laughed at each leap up and splash down. Some of us old fogies had seen performances like these before. Yet we were still lifted by the laughter born on the wings of these children. Hope was sprinkled in their glee. It promised a future that might lift us through the darkness. That evening I turned on TV and watched parents pull their murdered children from the rubble of bombed buildings in Ukraine and Gaza. The darkness returned. Did I mention that most of the children at the show were brown and Black? They also bore the accents, mannerisms and effects of being recent arrivals to America. They were not dressed in rags, rather they were appropriately decked out in their Sunday best. They were happy.

It has become somewhat acceptable to doubt whether the American dream still exists. In these cynical and polarized times it is customary to say that maintaining hope and trying to pursue opportunities to make a better life for yourself and your children is an old fashioned idea. I submit that the American dream is embodied in the spirit and aspirations of recent immigrants.

A hundred years ago the Italian, Irish, German and other workers risked everything to come to these shores, fighting for a chance to make their lives, their children’s lives, better. The eyes of new immigrants gleam with hope, like the eyes of recently emancipated African Americans who, like my parents, migrated to the North to escape Jim Crow and to find freedom. The hands of the people crossing the Mexican border bear callouses, similar to those who came here from Asia two centuries ago to lay railroad track. Then they cleaved out a crack, a mound, a laundry, a restaurant to make a place for themselves in this foreign alien land so that their seed could take root. And it did. That is who we are. That is who we have always been.

Now these new would-be neighbors come filled with hope, looking for an opportunity to carve their own Mount Rushmore, to construct their temples, to build their own pie in whose sky? The officials offer them bus rides, hotel rooms, tent cities and welfare. As if a hand-out could ever substitute for a hand-up. Like our grandparents these new neighbors are looking for hammers, shovels and an opportunity to use them. We need them not so much for the labor as the fact that they will reinvigorate the American spirit.

There is statue in New York harbor that some call the Statue of Liberty. Others refer to it as the Mother of Exiles. Near her is a proclamation written by poet Emma Lazarus. For some it was the first that our ancestors knew of the United States. It was a promise even more profound than the U.S. Constitution.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

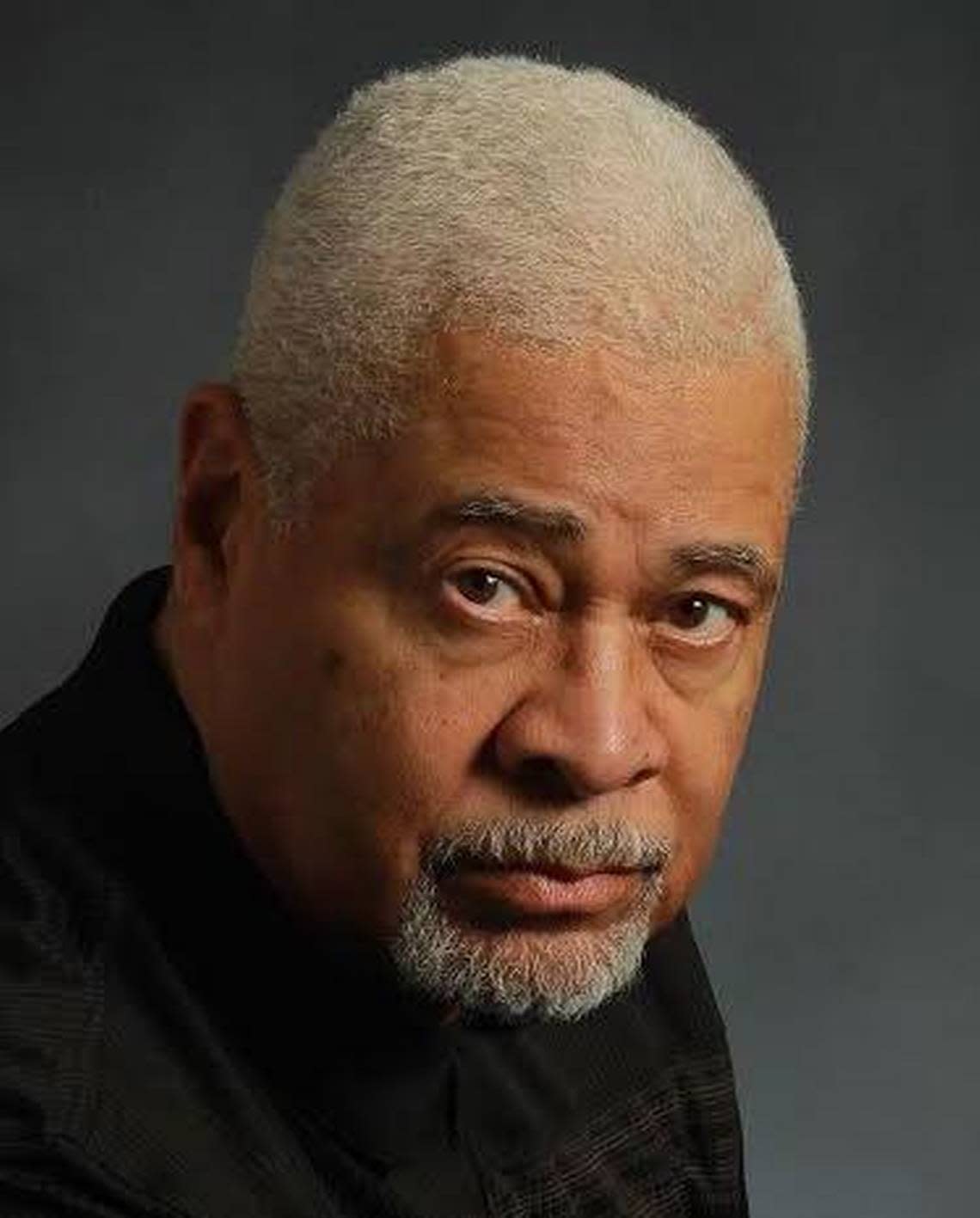

Charles Dumas is a lifetime political activist, a professor emeritus from Penn State, and was the Democratic Party’s nominee for U.S. Congress in 2012. He was the 2022 Lion’s Paw Awardee and Living Legend honoree of the National Black Theatre Festival. He lives with his partner and wife of 50 years in State College.