US Supreme Court scrutinizes anti-camping laws used against the homeless

By Andrew Chung and John Kruzel

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. Supreme Court justices confronted the nation's homelessness crisis on Monday as they wrestled with the legality of local laws used against people who camp on public streets and parks in a case involving a southwest Oregon city's anti-vagrancy policy.

The justices heard arguments in an appeal by the city of Grants Pass of a lower court's ruling that enforcing these anti-camping ordinances against homeless people when there is no shelter space available violates the U.S. Constitution's Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishments.

Some of the conservative justices appeared to question the lower court's decision or suggested that homeless people would have an alternate legal avenue to pursue. The liberal justices appeared ready to side with the homeless plaintiffs who challenged the city's laws. The court has a 6-3 conservative majority.

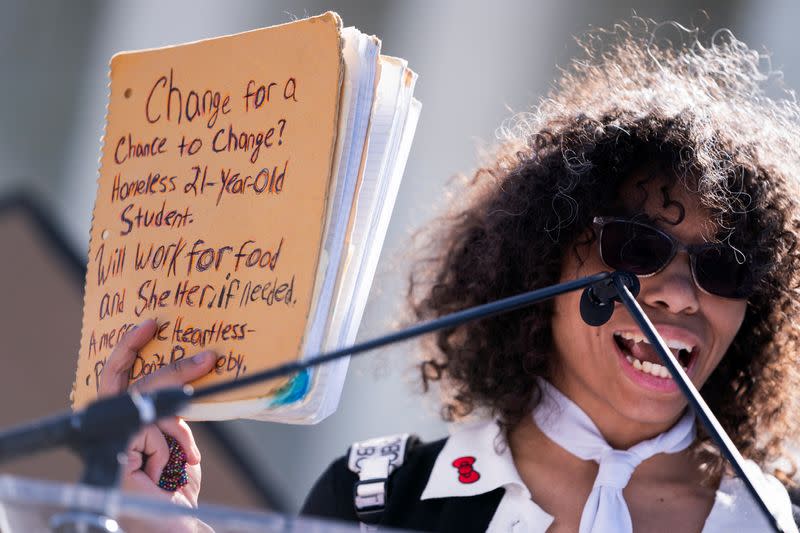

Advocates for the homeless, various liberal legal groups and other critics have said laws like these criminalize people simply for being homeless and for actions they cannot avoid, such as sleeping in public. They point to a 1962 Supreme Court ruling that the Eighth Amendment barred punishing individuals based on their status.

"A number of us, I think, are having difficulty with the distinction between status and conduct," conservative Chief Justice John Roberts told Kelsi Corkran, the lawyer arguing for the plaintiffs.

Roberts raised doubts that homelessness can be considered a status that would prohibit enforcing local laws.

"You can remove the homeless status in an instant if you move to a shelter, or situations otherwise change," Roberts said.

The justices waded into the complex societal problem of homelessness that continues to vex public officials nationwide as municipalities face chronic shortages of affordable housing. On any given night in the United States, more than 600,000 people are homeless, according to U.S. government estimates.

The case focuses on three ordinances in Grants Pass, a city of roughly 38,000 people, that together prohibit sleeping in public streets, alleyways and parks while using a blanket or bedding. Violators are fined $295. Repeat offenders can be criminally prosecuted for trespass, punishable by up to 30 days in jail.

"Where do we put them if every city, every village, every town lacks compassion and passes a law identical to this? Where are they supposed to sleep? Are they supposed to kill themselves, not sleeping?" liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Theane Evangelis, a lawyer for Grants Pass.

"This is a complicated policy question," Evangelis responded.

Sotomayor interrupted her, asking, "What's so complicated about letting someone, somewhere, sleep with a blanket in the outside if they have nowhere to sleep?"

'SOMEONE ELSE'S PROBLEM'

Liberal Justice Elena Kagan told Evangelis that the city's ordinance "goes way beyond" seeking to address encampments and public safety and makes it so a homeless person "can't take a blanket and sleep some place without it being a crime."

"It seems like you are criminalizing a status," Kagan added.

Corkran told the justices that the ordinances "make people with the status (of homelessness) endlessly and unavoidably punishable if they don't leave Grants Pass. Indeed, all the ordinances do is turn the city's homelessness problem into someone else's problem by forcing its homeless residents into other jurisdictions."

Proponents including various government officials have said such laws are a needed tool for maintaining public safety.

Justice Department lawyer Edwin Kneedler, arguing for President Joe Biden's administration, agreed with the plaintiffs that the city cannot enforce an "absolute ban" on sleeping in the city - which effectively criminalizes homelessness - but suggested that the injunction by the lower courts in the case was too broad and should be reconsidered.

Some conservative justices, while sympathizing with the dire circumstances facing many homeless people, seemed hesitant to conclude that the ordinances violated the Eighth Amendment.

These justices suggested that an alternative recourse for homeless people who believe they were unfairly cited or charged under the local laws would be to mount a defense under the legal theory of "necessity," arguing they had no other option, which can relieve a defendant of liability.

"If a state has a traditional 'necessity' defense," conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked Kneedler, "won't that take care of most of the concerns, if not all, and therefore avoid the need for having to constitutionalize" the issue?

The case, which began in 2018, involved three homeless people who filed a class-action lawsuit seeking to block the measures impacting them in Grants Pass. One of the plaintiffs has since died.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Mark Clarke ruled that the city's "policy and practice of punishing homelessness" violates the Eighth Amendment and barred the enforcement of the anti-camping ordinances. The San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Clarke's injunction against the ordinances.

A ruling by the Supreme Court is expected by the end of June.

(Reporting by Andrew Chung and John Kruzel; Editing by Will Dunham)