Vital Signs report shows youth, low-income earners struggling

They were 10 glorious years. But sadly, they're over.

The numbers in the latest Vital Signs report, released Thursday afternoon by Memorial University's Harris Centre and the Community Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador, show a province struggling with precarious employment and an uncertain economic future.

In the decade from 2005 to 2015, when oil prices soared and the province moved off equalization payments from the federal government for the first time, personal incomes grew and the percentage of low-income earners shrank — a lot.

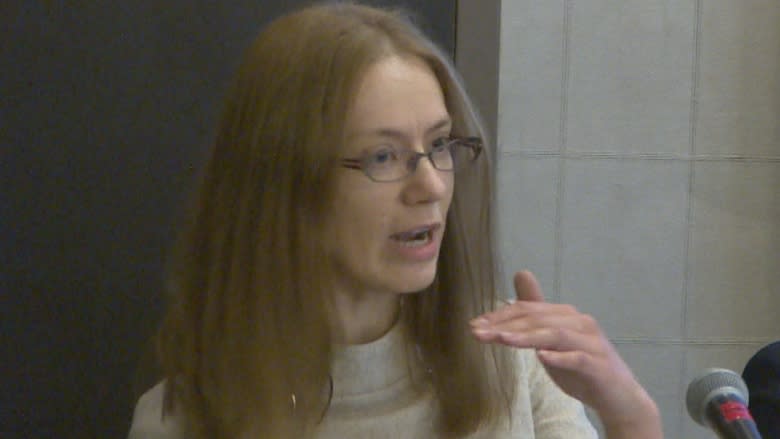

"We actually reached the national averages there," said Halina Sapeha, a researcher for the 2017 report. "Newfoundland and Labrador is usually very far behind the average."

MUN economist Doug May said the previous decade could be called "The 10 Glorious Years" by economic historians, but warned that the next decade "may not be so kind, especially to those at the top of the distribution."

'Worrisome trend'

The 2017 report shows that the percentage of low-income earners in the province is creeping back up.

"This is a worrisome trend, there is a danger here," said Sapeha.

Young people are also feeling the pinch.

Just under half the people in the province say they feel secure in their employment, the lowest number in Atlantic Canada, and a stark contrast to the 70 per cent in P.E.I. who say they're securely employed.

The uneasiness is felt both by workers who have steady jobs and are worried about cuts and layoffs, as well as workers who freelance and jump from contract to contract, said Sapeha.

"[That's] more and more a common labour market situation for youth," she said.

The report notes that Canadian student debt has shot up by more than 40 per cent since 1976 and housing prices have almost doubled. But people between the ages of 25 and 34 are making less money than they did in 1976, despite being far more educated.

Higher-than-average food bank use

Young people are also availing of the province's food banks in higher-than-average numbers.

Last year, of the five percent of the population who went to a food bank, 2.7 per cent were students.

The Canadian average for food bank use last year was just 2.4 per cent.

Seventy per cent of food bank users were on social assistance and 13 per cent were on employment insurance.

High levels of stress

Newfoundlanders and Labradorians report the highest amounts of stress in Atlantic Canada — 30 per cent compared with 24 per cent in P.E.I. and New Brunswick and 25 per cent in Nova Scotia.

Sapeha said although the numbers are grim, there are solutions. "I think the way forward is to think about ways to change the trend before it's too late," she said.

"There is an opportunity now to turn things around and think about potential ways to generate opportunities for young people and people who are stuck in this precarious lifestyle."

Strength in community

Sapeha — and the numbers — also emphasize that struggling Newfoundlanders and Labradorians have a strong circle of support, with the highest sense of belonging to their communities and to their province in the country.

Everyone surveyed in Bay Roberts and Grand Falls-Windsor said their neighbourhoods are a place where people help each other. In Corner Brook and St. John's, those numbers are still high: 88 and 87 per cent, respectively.

Community, said Sapeha, can help in rough economic times.

"I think this trend of economic uncertainty has its toll, but at the same time this is where communities could come together and help each other," she said.

"If the provincial government and federal government can't help to turn this around at least we as a community could do something for each other."