He waited two years for heart transplant at Jackson. With program suspended, time running out

Lyle Ryman had just arrived home from a procedure at Jackson Memorial Hospital for his weakening heart. He parked his truck and switched off the engine.

“And that’s the last I remember for six hours,” said Ryman during a recent interview with the Miami Herald. “My wife came down, found me — eyes rolled back in my head. I was drenched in sweat and shaking.”

An ambulance took him to Jackson North Medical Center in North Miami Beach, where doctors diagnosed him with a blood infection, a hurdle that would temporarily downgrade him on Jackson’s wait list for a new heart.

A couple of weeks later, his doctor, Dr. Anita Phancao called with worse news for the Miami Gardens veteran, who had been waiting over two years for a heart transplant at the Miami Transplant Institute, part of Jackson Health System, the taxpayer-supported public hospital network in Miami-Dade County.

“All I was told was that they were suspending the program, and that I could transfer to a new hospital or wait out the suspension,” Ryman said.

The Miami Transplant Institute, housed in Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, temporarily suspended its adult heart program in mid-March, upon the insistence of the nonprofit that oversees the nation’s organ transplant system. Both Jackson and the national group had received anonymous complaints about bad patient outcomes, including deaths and infections, after heart transplants at the institute.

Read: Probe of Jackson’s suspended heart transplant program expands; top surgeon can’t see patients

The complaints spurred the nation’s organ transplant system to send a team of experts to review the institute’s program. Also deployed to examine the program were federal Medicare/Medicaid officials and state officials who oversee Florida hospitals. The institute recently overhauled its physician leadership team.

READ MORE: He died after getting a heart transplant at Jackson. His loved ones want answers

‘A waste of my life’

Ryman was one of 15 people who was on the wait list to get a new heart at the Miami Transplant Institute when the institute suspended the program. The veteran, who was 69 at the time, chose not to be transferred to another hospital because he would be turning 70 just two weeks later and was told by his doctor that would make him ineligible to receive a new heart, he said.

Phancao had told him the age limitation came from the non-profit United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which oversees transplants around the country, he said. The national organ group, however, does not impose age restrictions for organ transplants. Some hospitals accept sicker, older patients, some do not.

In a statement to the Herald, Jackson said no single factor would make a patient ineligible for a transplant. When asked whether Phancao cited an age limit, Jackson said, “There is no evidence in his medical notes to indicate that.” Ryman had not been removed from the transplant list and had chosen to stay with institute, Jackson said.

But as additional reporting has emerged about the heart transplant program and its problems, Ryman has become increasingly angry. He thought about the multiple infections and issues he had while seeking treatment there.

“All the things that I went through were a waste of time,” he said. ”...A waste of my life.”

Now, Ryman is researching other transplant centers, with plans to ask the VA hospital for a transfer.

‘Gotta be strong-minded’

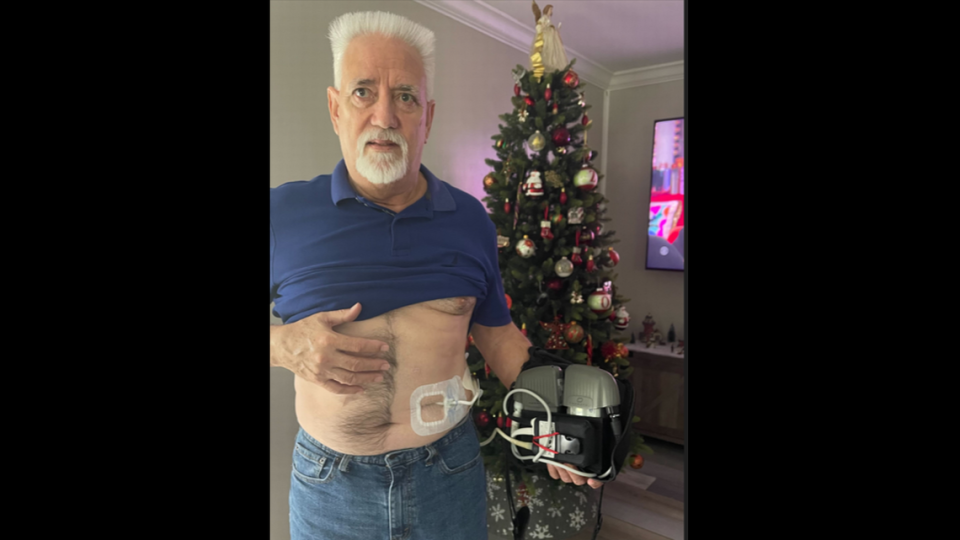

For Juan Llanes, family is everything. Sometimes, his grandson likes to listen to Llanes’ heartbeat.

It sounds different from his grandson’s. Instead of ba-bump, ba-bump, Llanes’ heart sounds more like a machine — ba brr — because of the mechanical pump implanted in his chest.

The pump, a left ventricular assist device, also known as an LVAD, is helping keep Llanes alive while he waits for a new heart. The 65-year-old grandfather has end stage heart failure. He was a level four on the heart transplant wait list at the institute before the suspension — one being most severe, six being the least.

He’s currently “inactive” because of the institute’s suspension of its adult heart transplant program, which means he won’t be considered for a heart until the program reopens or until he transfers to another center.

Llanes has chosen to wait out the program’s suspension because of how well Jackson’s staff has treated him, he said. Phancao and Dr. Matthias Loebe, the former chief of the heart transplant program, were his doctors. He’s also on Jackson’s wait list for a kidney.

“From the very first day, they treated me so good that I can’t complain,” Llanes said. “Besides, if I go anywhere else, I have to start from scratch. I have to go through all the screenings, all the things, and everything so it’s going to take longer anyway.”

Llanes’ first signs of heart problems began with discomfort in his stomach. Then on Jan. 16, 2021, he had a heart attack at home. He was taken to the hospital, where doctors inserted a stent in his coronary artery to help restore his heart’s blood flow. He went into multiple-organ failure, cardiogenic shock and was taken to Jackson, where he was placed into a medically induced coma for two weeks and on dialysis for two months.

Phancao and her staff, with consultation from Loebe, decided a heart pump was his best chance for survival. In March 2021, he underwent surgery. The next year, his doctors determined he could be a possible candidate for a heart transplant and added him to the list.

It’s unclear when Jackson’s adult heart transplant program will reopen. Llanes is focusing more on enjoying life with his family, rather then his placement on the list.

“I’ve been through hell. I died. I came back from that. I’m here, I have a great family. And I’m telling you, I never been afraid of anything. I’ve never been afraid of anybody,” he said.

Still, whenever he sees Jackson’s phone number appear on his phone, he can’t help but think: “It [a new heart] might be here.”

“It’s not hard, but to be able to put up with something like that, you know, you gotta be strong minded,” he said.

READ NEXT: This heart pump can be a better option than a transplant. But it’s not for everyone

Four trips to Jackson over three years

Ryman has heart failure, but says he’s otherwise healthy. Like Llanes, he was at level four on the list before the suspension.

He went to the Miami Transplant Institute at Jackson Memorial three times over the past three years, thinking he would get a new heart. His fourth visit occurred weeks before the institute suspended its adult heart transplant program.

READ NEXT: How do Florida hospitals get organs for the sickest patients in need of transplants?

For a person who needs a new heart, certain factors — distance from the donor’s hospital and whether a patient has a heart pump or other support device, such as an intra-arterial balloon pump — help determine their urgency status, according to the heart allocation policy of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The balloon pump is often used as a “bridge” to help keep patients alive while they await a heart transplant. It usually elevates a patient’s status to a level 2.

Ryman’s first trip to Jackson was in 2022 to get the balloon pump inserted into his chest. But he said he was told he had a blood infection and could not get the pump. The infection also made him temporarily ineligible to get a heart transplant.

The second time he was brought in for the balloon procedure, he tested positive for COVID just two days later. He got the balloon pump put in while he was in isolation for two weeks, but no new heart.

The third time he went to the hospital, Ryman had a catheter inserted to monitor his blood pressure and oxygen levels.

The fourth time he was at Jackson was in March, just weeks before the adult heart transplant program was suspended. He went in for an echocardiogram, where a dye is injected into his arm to allow contrast to show in a cardiogram. After he was discharged, Ryman began to shake in his truck. After a few minutes the shaking subsided, so he said he drove home. Tremors, shaking and feeling cold are side effects that can occur from the dye.

Ryman then woke up in Jackson North’s emergency room six hours later, diagnosed with a blood infection.

Medical team disagreements about what was happening to him or issues with medications prescribed by different doctors were common, he said.

But once he complained to Phancao about the medication issues — whether it was side effects or different medications interacting poorly with one another— she got it sorted out, he said.

“She did everything she possibly could for my medical care,” Ryman said. “She was always there.”

Top leadership changes

Complaints about Phancao and the LVAD program are at the center of a report, reviewed by the Herald, that was sent to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid a few weeks ago. In a staff meeting last week, Jackson leaders announced an overhaul of the Miami Transplant Institute’s leadership team for its heart program:

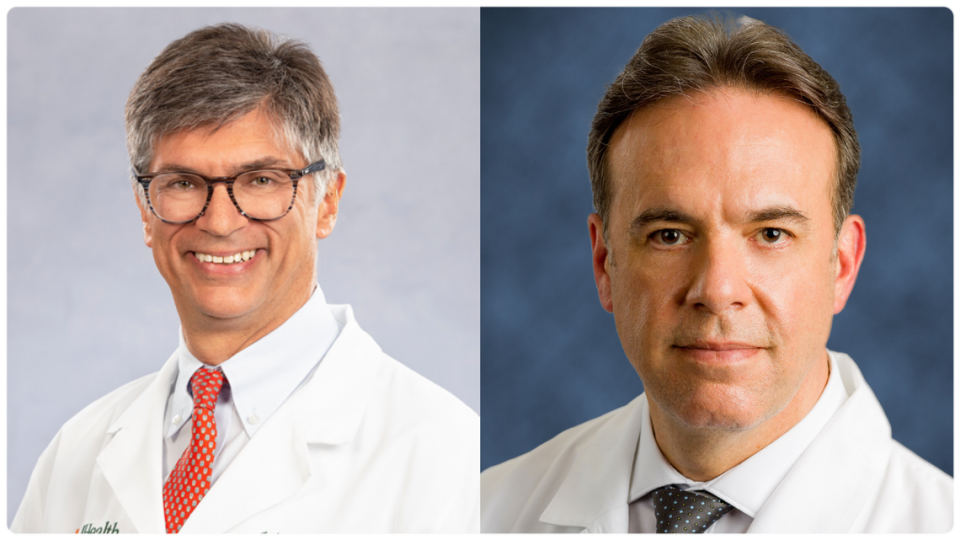

▪ Dr. Joshua Hare was named the new interim chief of heart failure for both Jackson and the University of Miami Health System, whose doctors staff the transplant institute. Hare, a cardiologist, is head of the University of Miami’s Interdisciplinary Stem Cell Institute and a pioneer in stem-cell research.

▪ Dr. Leonardo Mulinari was named new interim chief of heart transplants. Mulinari is chief of pediatric and congenital heart surgery at UM’s Miller School of Medicine and co-director of the Comprehensive Heart Center at Holtz Children’s Hospital, located at Jackson.

These positions were previously held by Phancao and Loebe, respectively. The hospital did not announce the changes publicly but confirmed the shakeup to the Miami Herald, which learned of the leadership change independently.

What comes next

Since Ryman is a veteran and the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs oversees his care, his process is likely a bit different from other patients.

He went back to the VA and on May 1 had an electrocardiogram — which records the heart’s signals to test for different conditions. The procedure was part of the process to see if he could be referred to another transplant program.

The VA has since given him the OK to transfer to another center. He’s considering switching to the heart transplant program at Cleveland Clinic Weston in Broward County or Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

“My expectations as to what I’d like to see from here? Well, I guess I’m going to be on medication for the rest of my life, however long that is, because I’m not going to do an LVAD,” said Ryman. “And if somehow for some reason I could get a heart transplant, I’d be all for it. Not there [at Jackson]. But if I could get a heart transplant, it could certainly extend my life and my quality of life.”