Watch for Lyrid fireballs to light up the sky Sunday night

Night sky enthusiasts rejoice! The spring meteor shower drought finally ends this weekend as the Lyrids reach their annual peak.

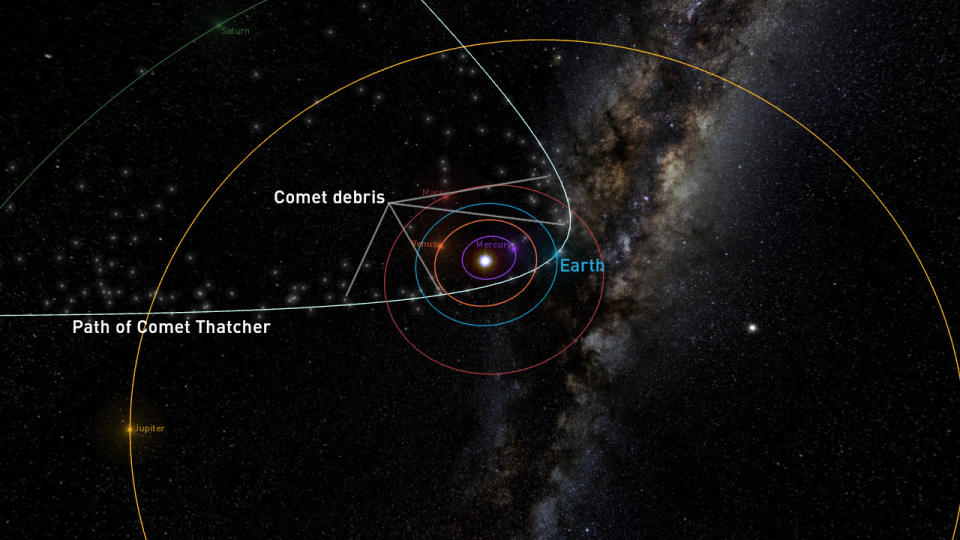

On the night of April 14, as Earth travelled along its orbit around the Sun, the planet slipped into a fast-moving stream of icy debris left behind by an ancient comet known as C/1861 G1 (Thatcher).

As these bits of comet debris began plunging into the atmosphere, they produced streaks of light in the sky and marked the beginning of the annual Lyrid meteor shower.

This simulation shows the orbit and debris stream from Comet Thatcher, as viewed from far 'above' the solar system's orbital plane. The locations of the inner planets are indicated as of April 22, 2024, with Earth very close to the orbital path of the comet. Credit: Meteorshowers.org/Scott Sutherland

The Lyrids typically start off fairly quiet, with only a handful of meteors streaming out of the constellation Lyra each night for the first week of the meteor shower.

However, on the night of April 21-22 we pass through the densest part of comet Thatcher's debris stream.

That is when the Lyrid meteor shower reaches its peak, producing around 20 meteors per hour throughout the night.

The radiant of the Lyrid meteor shower is shown in this simulation of the night sky for April 22, 2024, along with the Waxing Gibbous Moon. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The number of Lyrid meteors is fairly consistent year to year. However, sky conditions have an impact on exactly how many meteors an observer may see during the shower's peak.

To maximize your potential for spotting these brief flashes of light, check your weather forecast and look for "partly cloudy" or "clear" skies. Also, the event is best viewed from somewhere with a dark sky, far from city lights.

Additionally, just as with urban light pollution, moonlight can take its toll on how many meteors we see. With the Lyrids peak timed to occur just two nights before the Full Moon, some of the dimmer meteors could be washed out by moonlight.

DON'T MISS: Eclipses and meteor showers. What to watch for in the sky in Spring 2024

Fireballs and outbursts

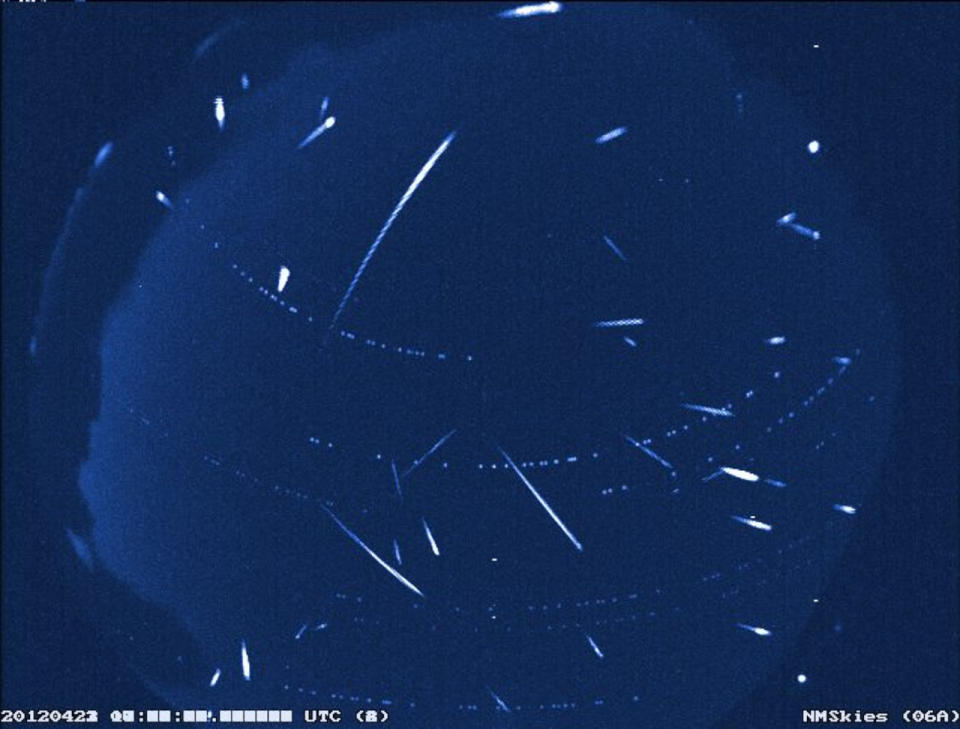

Fortunately, the Lyrids is one of the annual showers that tend to produce exceptionally bright meteors known as fireballs.

A fireball is any meteor that shines at least as bright as the planet Venus in our sky. They are common during the Lyrids due to the exceptional speed that comet Thatcher debris travels at — around 100,000 km/hr — when it hits Earth's atmosphere.

This composite all-sky camera image shows a mix of Lyrid and non-Lyrid meteors over New Mexico from April 2012, including a few Lyrid fireballs. NASA/MSFC/Danielle Moser.

Lyrid fireballs are even bright enough to be seen with a Full Moon in the sky. So, keep an eye out for them throughout the night.

Also, if you are out observing the Lyrids, consider that you're viewing the oldest of all the meteor showers we see each year. According to records, it's been observed for over 2,700 years!

Plus, while we only see around 20 meteors per hour from the Lyrids, every 60 years, there's an 'outburst' of activity.

According to Sky and Telescope magazine, "Chinese court astronomers reported a Lyrid outburst on March 16, 687 BC when 'in the middle of the night, stars fell like rain.'"

In 1982, during the last outburst, the Lyrids rivalled the August Perseids, as it produced over 100 meteors per hour during its peak. The next such outburst is expected in 2042.

Related: Want to find a meteorite? Expert Geoff Notkin tells us how!

Meteor? Meteoroid? Meteorite?

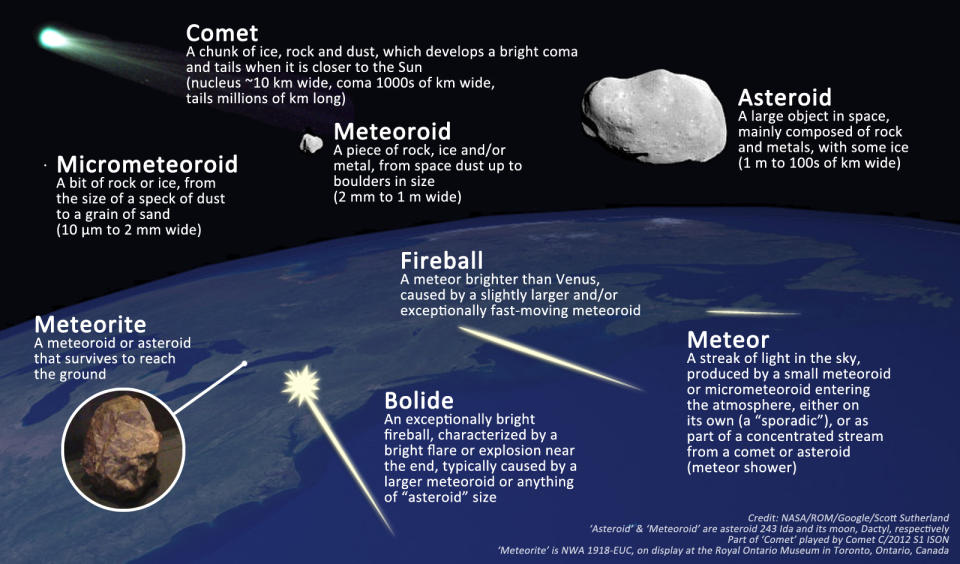

There are a lot of similar-sounding words that get tossed around during events like these, and it's easy to get them mixed up. So here's a short guide to help.

The bright streaks we see during the Lyrids are known as meteors.

Image via Unsplash: Austin Human @xohumanox

Each meteor occurs due to a meteoroid — a piece of rock or ice the size of a speck of dust up to a grain of sand — plunging into Earth's upper atmosphere.

Meteoroids travel at speeds measured in kilometres per second. When one hits the atmosphere, the air in its path becomes compressed into white-hot glowing plasma, which is the source of the meteor flash we see. Sometimes meteors can shine in different colours — green, blue, yellow, etc. — sometimes due to the light the air itself emits when it becomes ionized, but also due to specific minerals vapourizing off the meteoroid as well.

A typical meteor flash tends to last a second or less.

Larger meteoroids, from a pebble to a boulder in size, produce much brighter and longer-lasting meteors, which we call fireballs. Some fireballs emit bright flashes along their path, which indicates that the meteoroid is breaking apart due to the intense pressure exerted on it by the atmosphere. These are often referred to as bolides.

Regardless of how big and bright a meteor is, it 'winks out' when one of two things occur:

the meteoroid vapourizes (typical for smaller ones), or

the meteoroid is slowed enough by its passage through the atmosphere that it can no longer exert enough pressure to compress the air in its path into a plasma.

In the second case, any surviving parts of the meteoroid enter 'dark flight' as they plummet to the ground. In rare cases, these can be spotted by doppler weather radar during the final phase of their journey.

If we find these rocks at some point after they hit the ground, we call them meteorites.