Watch our seasons go topsy-turvy without leap years

Thursday is a special day, when we're going to see something that only occurs once every four years or so. We're going to have a Leap Day.

A leap day is a little pause — if you will - in the normal progression of our modern yearly calendar. Every four years, give or take, we tack an extra day onto the end of February. This lengthens that specific year from 365 days to 366 days, but the additional day also has an even more important function.

Without it, the seasons and our calendar would slowly drift out of alignment.

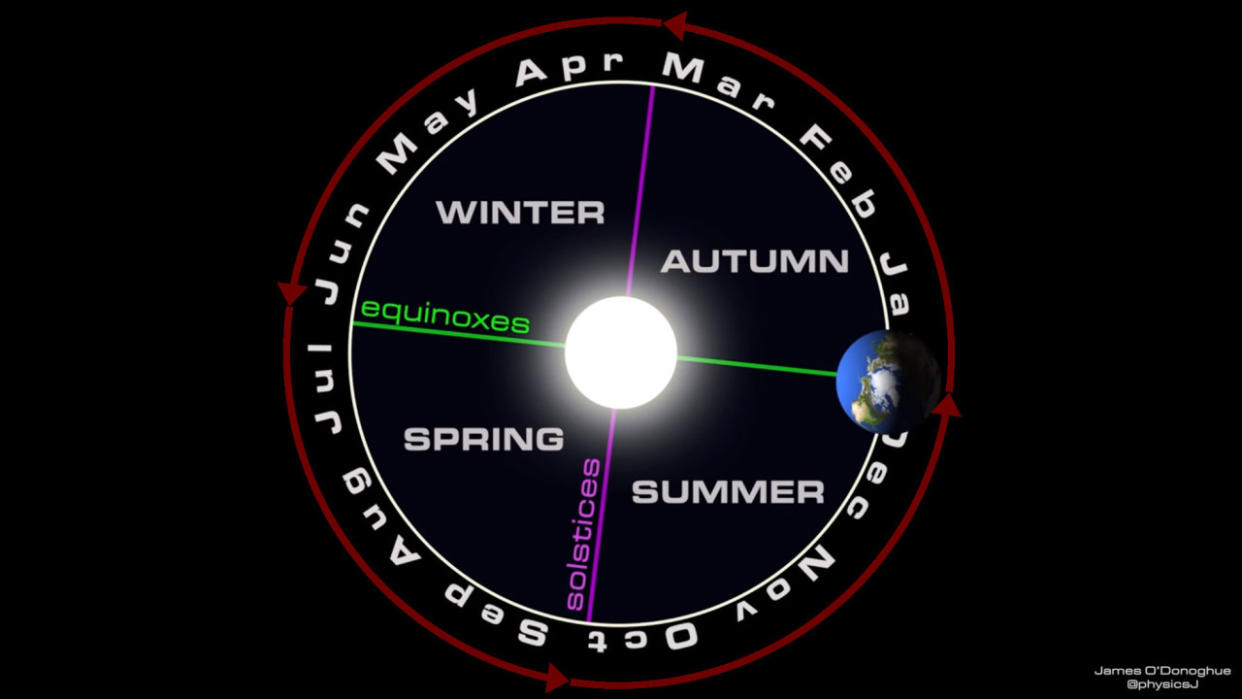

This video, made by Dr. James O'Donoghue, a planetary scientist at the Japanese space agency, shows exactly what would happen if we did not have leap years.

DON'T MISS: Everything you need to know about the April Total Solar Eclipse

In just over 400 years, the timing of the seasons drifts away from the calendar so far that we'd be off by a full season. Thus, in the year 2425, we'd observe winter from March through June, spring from June through September, summer from September through December, and autumn from December through March.

It takes a long time to see significant impacts. However, just adding one day to the calendar every four years or so avoids this whole problem.

What's going on here?

Our yearly calendar is very precise, counting out 365 days each time we go around the Sun.

However, there's one problem: that's not how long it takes Earth to travel around the Sun.

When viewed from any particular place on Earth, it takes the Sun about 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 45 seconds to return to the exact same point in the sky each time we go through the four seasons. This is known as a solar year.

Watch below: Planetary scientist Dr James O'Donoghue traces Earth orbit through a full year of seasons.

So, each year we have roughly an extra six hours to account for. You can see the effect of this by looking at the exact timing of the seasons.

In 2020, the spring equinox occurred on March 20 at 3:49 a.m. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). In 2021, it had advanced to 9:37 a.m. GMT, in 2022 it was at 3:33 p.m. GMT, and in 2023 it was at 9:24 p.m. GMT.

Without a leap day in 2024, the equinox would occur at 3:06 a.m. GMT on March 21. Tacking February 29 onto the calendar pulls the equinox back a full day, though, ensuring it stays on March 20. (Note: time zone also factors into this, as 3:06 a.m. GMT on March 20 is 11:06 p.m. EDT or 8:06 p.m. PDT on March 19. It's the year-to-year consistency that matters most, though.)

Now, we've made the exact timing of the equinoxes and solstices fairly immutable. As our tilted planet orbits the Sun, the equinoxes occur at the exact moment we see the Sun cross the celestial equator. The solstices happen at the exact time when the Sun reaches its highest or lowest point in the sky. The hemisphere you're in — northern or southern — determines which equinox or solstice you're observing at the time.

This 'solargraph' shows the Sun's path across the sky for each day between February 28 and the June 20 summer solstice in 2016. Credit: Bret Culp - Used with permission.

Altering when the seasons occur is a bit beyond our capabilities right now, as we'd need the ability to shift Earth's orbit around the Sun. However, one thing we can change is our calendar.

As a simple correction to account for the extra time, we use leap days. Since each year adds roughly six hours, we add an extra day in our calendar every fourth year.

There's one more consideration, though. An extra day every four years corrects for a total of 6 hours. Thus, it over-corrects by 11 minutes and 14 seconds.

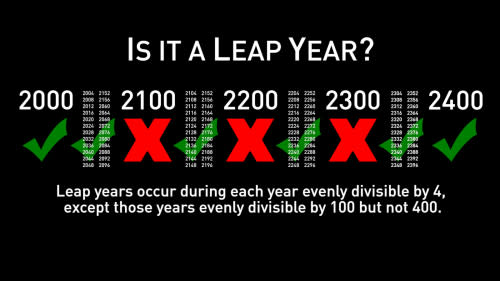

To prevent an even slower 'wander' of the seasons in the opposite direction, we skip a few leap years. Specifically, each time we come around to a year that is evenly divisible by 100, we skip it, unless that year is also evenly divisible by 400. This means that every 400 years, we skip over 3 leap years.

As shown above, the year 2000 was a leap year (evenly divisible by both 100 and 400). Every 4th year afterwards is also leap year. However, we skip the years 2100, 2200, and 2300, as they are evenly divisible by 100 but not 400. Then, 2400 is another leap year and the pattern repeats.

If that seems a bit complex or even arbitrary, it is definitely effective. Just by adding this relatively simple correction to how we keep track of our years, the calendar can stay almost perfectly in sync with our astronomical seasons.