Wes Anderson Talks About Roald Dahl’s ‘The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar’, Teases His Next Movie, And Claims: “I Don’t Have An Aesthetic”

Despite fears for the future of film in the new, seemingly disposable digital era, there are still many auteurs holding on out there in the modern movie landscape. For example, there’s Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan and even Michael Bay (for, as director Tarsem said of the latter’s work, “You may not like it, but you know who made it”). But few directors are as instantly recognizable as Wes Anderson. Nothing happens by accident in a Wes Anderson movie: the camera moves are perfectly choreographed — sideways tracking shots are a specialty — and the sets don’t even begin to aim for realism. Clothes are tailored, hair and makeup is scrutinized all the way down to lipstick and nail polish, and music is key, creating a subtle, sometimes melancholy and always wholly effective emotional backdrop.

Even when Anderson branched out into animation, with Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), he took that sensibility with him. But what also came out of that project was an enduring and wholly unexpected connection with the works of British author Roald Dahl, author of joyously anti-authoritarian romps for kids and ominous morality tales for adults. Having forged a link with the Dahl estate, Anderson has since returned to that wellspring of ideas for a series of short, live-action films that show a remarkable degree of synthesis between the director and the author, who died in 1990 aged 74.

More from Deadline

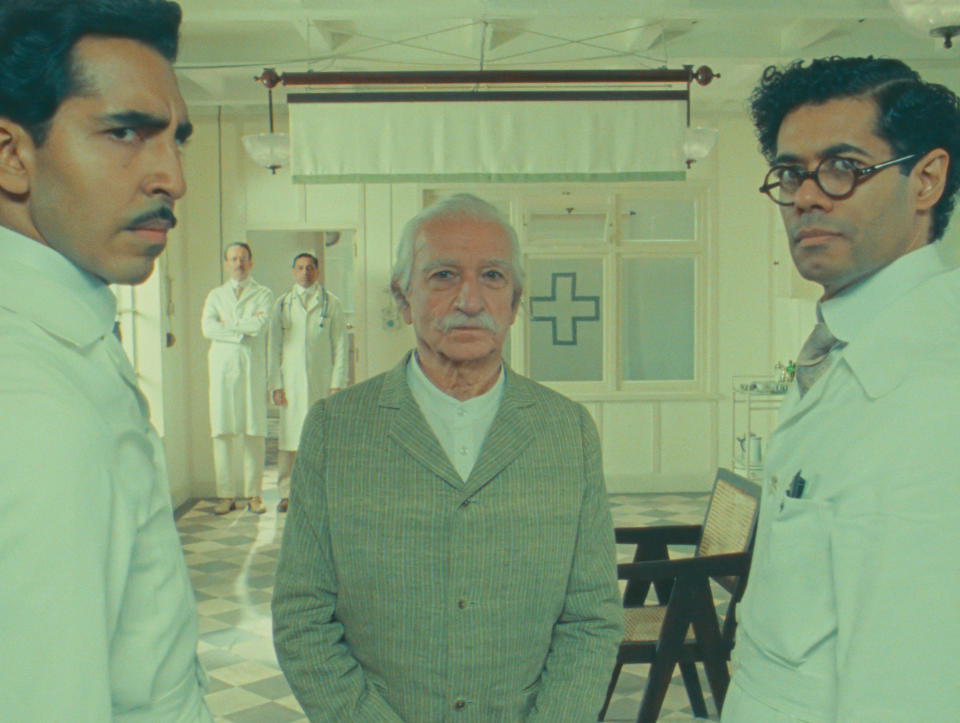

The flagship short is The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, the head-spinning story of a wealthy idler (Benedict Cumberbatch) who discovers the story of an Indian mystic who can see with his eyes closed and applies those ideas to gambling. Like The French Dispatch, it’s full of neat camera tricks; doors open into and onto other worlds; in one funny sequence, Cumberbatch grows a beard in the blink of an eye. And after Henry Sugar bows on Sept. 27, adaptations of Dahl stories The Swan, The Rat Catcher, and Poison follow on Sept. 28, 29, and 30 respectively.

This conversation took place in Venice the day after Anderson was awarded the festival’s Cartier Glory to the Filmmaker Award, in a centuries-old private villa (with a very modern elevator) where strong caffettiera coffee, traditional Italian cookies, HB pencils and A4 sheets of paper were never far from hand…

DEADLINE: Let’s start with The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar. Is this part of an ongoing project that you’re doing, or does it stand alone?

WES ANDERSON: It’s a sort of a standalone, short film, but it’s also the reason why we’ve made a whole group of them. Because for a long time I’ve had this idea to do Henry Sugar. But when I realized that it was only going to add up to a certain length, I had to say to myself, “Let’s just let it be what it is, and this is the length that it wants to be.” So, I’ve made some other short films that are separate, but they’re all Dahl. And so, there’s three other ones that’ll be released one by one, or however Netflix want to do it.

DEADLINE: Tell me a little about the next three.

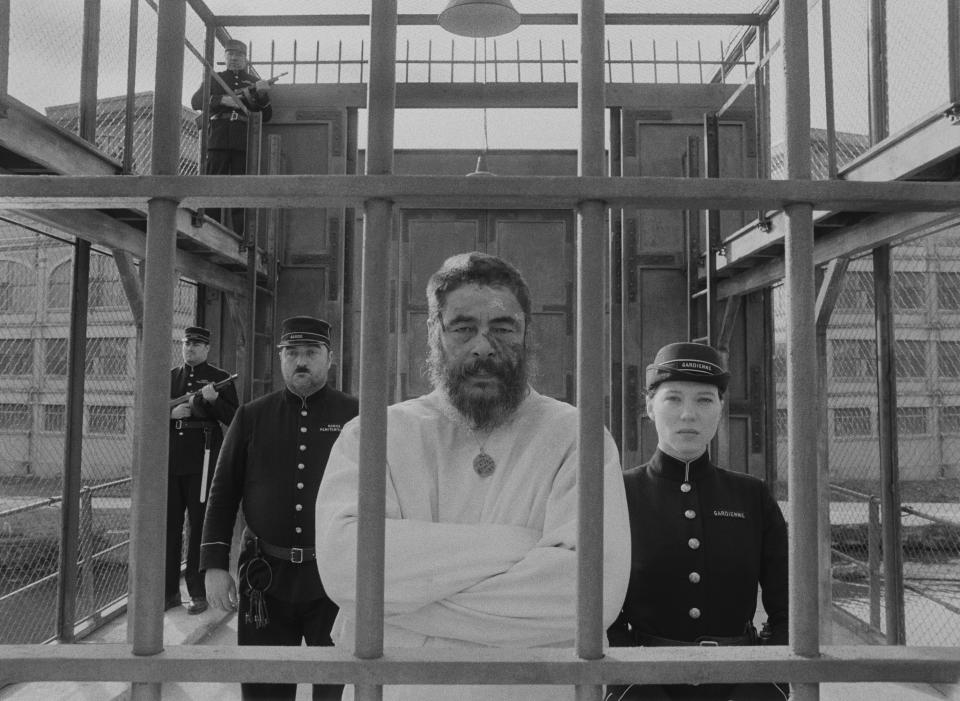

ANDERSON: Well, there’s one where Ralph Fiennes plays a rodent exterminator. It’s a story called The Rat Catcher that Dahl wrote, I think, in the ’50s. That’s got Richard Ayoade, and it’s got Rupert Friend. Just a little group. It’s probably 13 minutes, or something like that. Henry Sugar is the longest one [of the project]. Significantly longer. It’s more than twice as long as any of the others. Then we also have one called Poison. That’s an old Dahl story. Maybe from the early ’40s, or mid-’40s, I guess. For that one, we’ve got Benedict Cumberbatch again, we’ve got Ben Kingsley again, and we’ve got Dev Patel again. So that’s a completely different group from The Rat Catcher. And we’ve also done The Swan, which is from The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More. That’s essentially just Rupert Friend, who was great by himself. And that’s quite a short one as well.

DEADLINE: Why those stories in particular? Are you done with Dahl after this, or will you be going back, do you think?

ANDERSON: Well, the thing I’d say is that… [Pauses] Henry Sugar, I just couldn’t figure out how to adapt. I just didn’t see a way to do it. And then it was the idea of using his description of it, really, that appealed to me. I thought, “Well, that would be fun to do. I could see a way to do that.” Because I realized that much of what I’d always loved about the story was simply his voice throughout it, and I said, “Well, there’s one way to keep his voice — just use it.” And so that’s what we did.

So, once I’d done that, I went, “Well, which other stories seem suited to this method?” It felt suited to Henry Sugar, but maybe not to every story. And so, I kind of found ones that I thought could be sort of ‘performed’. And so that’s how I picked the others. I mean, there’s another story in The Rat Catcher called The Hitchhiker, which is probably very suitable also, but something was just too familiar about it. Then there are others that would be too long and complex, and so, after doing Henry Sugar, I thought, “Let’s just make some little ones, not another 40-minute one.”

DEADLINE: Roald Dahl was also very well known in the UK as a storyteller, not just an author. The books were obviously very famous, but he also had the TV series Tales of the Unexpected, which he would introduce himself, sitting in front of the fire.

ANDERSON: Yes. In our house, we have a recording of Dahl reading Fantastic Mr. Fox. He did record himself doing quite a few of [his books]. There’s also a reasonable amount of documentary stuff about Dahl. In fact, when we started filming Henry Sugar, Ralph was on set, in the little space that’s a recreation of Dahl’s workspace, and I could hear him talking to himself. I said, “Tell me what you’re saying.” It turned out that he’d been observing Dahl from the archival stuff I’d sent him, and he knew Dahl’s little rituals. He was acting them out on his own, just in preparation. And I was like, “Start over, start over! We’ll film this!” And so, the movie begins with Ralph completely improvising. Every take was a bit different, because it’s Ralph just sort of channeling Dahl getting ready to write. Ralph is so interesting and authentic.

DEADLINE: There are a lot of people in these films that you’ve worked with before. Do they always know exactly what you want from them? So much of Henry Sugar seems incredibly perfect in terms of the performance, and the timing especially.

ANDERSON: Some of it, they definitely were aware of technical things, like, “OK, here’s when the room is going to change and the wall is going to move.” All that sort of stuff. But everybody has their own way. For instance, with Richard Ayoade and Dev Patel, there’s no appearance of any effort to memorize the [lines]. They seem to just have it. They’re younger, you know? Benedict is interesting, because Benedict is probably the same age, but Benedict has a different thing. He’s attacking the role this way and then he’s attacking it that way. And with Ralph, you’re aware of him carefully preparing, preparing, rehearsing, rehearsing … There’s a lot of repetition. I mean, normally when you work with Ralph, he’s got everything he needs. He’s got his role completely down. He’s absolutely beyond word-perfect. He has everything kind of absorbed. But, in between, you can hear that he’s working on the thing he’s doing next. He’s working on memorizing a play, or some big text that’s going to take a lot of work, so he’s already prepping the other thing.

DEADLINE: Talking of Benedict Cumberbatch, in Henry Sugar, when he goes off screen and comes back with a beard, did you cheat that or is that in real time?

ANDERSON: [Laughs] I think we might’ve tightened it up.

DEADLINE: Ever since Rushmore, you’ve had the idea of plays within plays and stories within stories…

ANDERSON: Yes.

DEADLINE: But I’ve noticed more and more since The French Dispatch that you’ve become more interested in the physicality of doing that in camera, or giving the illusion of doing that in camera.

ANDERSON: Yes.

DEADLINE: And this is perhaps the ultimate story-within-a-story story because, before the audience really realizes it, you’ve gone from rural India to a casino in London.

ANDERSON: I like stories that are stories within stories and plays within stories and movies within plays within stories. [Laughs] But I think this story, Henry Sugar, may have been the first thing I ever read that that made me kind of intrigued by that concept. Like, “Oh, so now we’re going into the book that he found…” It has layers and layers and layers. I liked that when I read it as a child, and it kind of stuck with me. This thing in particular seemed like … [Pauses] You know, there’s a movie that I thought of, called Swimming to Cambodia. Did you ever see that?

DEADLINE: The Spalding Grey monologue movie?

ANDERSON: Yes. And Jonathan Demme made the movie of it. And Jonathan Demme … You know, he had his movie-movies, some of which were great, big Hollywood movies. But then he also had these sort of “side” movies. He did many documentaries and performance things. They’re not avant-garde films, but they’re films about sort-of-avant-garde artists or something along those lines. Performances by people who were in the distinctly avant-garde world and had become a bit more broadly known. Anyway, this one, Swimming to Cambodia, I must’ve seen it in high school, I think, and I always think back on it. And I love the idea that we are kind of riveted in that film by a guy that’s just sitting at a table talking. But it’s such a dynamic performance and the stories are so interesting that you’re just totally engaged from start to finish.

DEADLINE: After you hired him for Asteroid City, Jeffrey Wright said that you were very familiar with his work as a stage actor. Are you an avid theatergoer, and have you thought about doing theater yourself?

ANDERSON: I first saw Jeffrey in Basquiat. But then I saw him in a play called Topdog/Underdog, and then I saw him in another one called A Free Man of Color, a John Guare play. And then, after that, I’d see him in other movies. I loved him in Angels in America — he was in the original production of Angels in America, which I didn’t see. I saw Mike Nichols’ movie, though. He’s one of the few actors who played the part in the original production. And he’s so good in it. He plays this character, Belize.

I go to the theater now and then. When I lived in New York, I went more. When I’m in London, I’ll go. Did you see the one at The National [Theater] about Richard Burton and John Gielgud? The Motive and the Cue. It’s a Sam Mendes play. He’s, I think, the best stage director. I mean, I don’t know. I’m no expert. But every time I see a Mendes play, I’m always just dazzled by it. The Lehman Trilogy, did you see that one? That was quite great. And he did The Ferryman, which was very good. Is that a Jez Butterworth play? Yes, it is. I remember talking to Mike Nichols — me and Noah Baumbach — years ago. Now, Mike Nichols knows his way around the stage, and he always admired Sam Mendes for his stagecraft.

DEADLINE: Do you get inspired by the physicality of theater?

ANDERSON: Yes, most likely. Roman Coppola, who has been my collaborator for years and years, grew up very interested in magic tricks, and he’s very well versed in movie techniques that resemble magic tricks. Things done with mirrors; things done with deception of some kind, so that it seems to happen right in front of you. I’ve always loved that. You see that it’s not what it purports to be, but maybe it’s also real in its own way too.

DEADLINE: What’s interesting, looking back on your filmography, is that every film is separate and it’s its own thing. They all have a different world, a feeling, soundtrack, approach. How is it possible to do that?

ANDERSON: Well, first of all, the key thing is that it doesn’t happen all at once. I mean, when you do a movie, it slowly accumulates. The first movie I directed, Bottle Rocket… [Pauses] It was a long time ago; 26 years, I think. One of our producers was James L. Brooks — a great director, writer, and producer. He kind of picked us. He’d learned about us through Polly Platt, his first lieutenant, his collaborator. So, Polly and Jim were the producers, but Polly was the one who was actually with us [on set]. Polly had been married to Peter Bogdanovich years before, and on the day before we were going to start filming, she got a call from Peter. They had children together, and they talked a lot. She said, “Peter, why don’t you talk to Wes?” And she put him on the phone. I’d never met him, but he was a big name for me, because of The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon. Particularly these earlier films. I had seen them again and again and again. I mean, The Last Picture Show was a bit of a bible for me and Owen Wilson.

And so I talked to Peter. He asked me some questions, like, “How many days you got? What are you going to do with that?” And at the end he said, “I’ll tell you what Roger Corman told me when I was directing my first movie. And it’ll sound obvious, it’ll sound like something that goes without saying, but it’s not: Take it one shot at a time.”

He was right. You realize when you’re doing it that you’re so often trying to say, “OK, well, we’ve got to do this scene, and it’s going to lead to that scene, and then the next one.” But if you just say, “I need to this one scene to work right,” it will lead naturally to the next thing. You focus on it, and you accomplish it. You don’t think about the whole thing. And in terms of how to create a movie, that’s usually how we do it. We say, “OK, well, let’s just get this little bit done. When this part really feels right, then we’ll focus on what’s going to happen after that, and how we are going to bring it to life.” Anyway, that’s my thought about it.

DEADLINE: You seemed to hit your stride with The Royal Tenenbaums. Rushmore was sort of halfway there, but Tenenbaums was all the way there, in terms of what you were going to be doing from then on. It was perhaps the clearest expression of your aesthetic.

ANDERSON: Well, I don’t have an aesthetic. To me, what I have is…

DEADLINE: Erm, I think some people will disagree with that!

ANDERSON: [Laughs] Which I totally understand! Even I can say, “Well, yes, I can tell that’s the same person.” But it’s an invention, you know? What I was doing in Bottle Rocket was what I had. That was my aesthetic. And it changed in this one. And, every time, so much of the next movie is informed by something we did in the one before. Like, people often refer to me doing these kinds of dolly shots, and Asteroid City begins with a long one. We go from one place to the next, and we run around. It’s a certain kind of way to film a sequence that is not so typical for everybody. And I do it a lot.

Well, I know exactly when I started to do it, and I know why, which is a rare thing with this type of thing. When we were doing Rushmore, there was a scene that took place on a baseball diamond. I had this whole scene planned. It was with a big crowd, and we were going to use handheld shots. We arrived in the morning, and it was absolutely flooded. I said, “Well, let’s see how long it’s going to take to dry.” But it was clear that the scene would be about mud if we filmed on this baseball diamond. Now, the scene is written in a way where it sort of had to be on that baseball diamond, between home plate and third base …

I don’t know if you can picture it. [Laughs] I don’t know if you even know baseball! It’s the edge of the pitch, you might say. There’s a thing called the dugout, which is where the players go away to go up to bat, and there’s a strip to the side of it, and I just decided, “We’ll put everything over here. We’ll lay a great big dolly track, and we’ll play the scene all the way this way, and then we’ll play the scene all the way that way. We’ll just use the little bit of set that we have.” And when I did it, I thought, “Well, I liked that. That was interesting and I enjoyed it.” And so I feel like I’ve been doing variations of that ever since. That’s why I do those — because the baseball diamond was too flooded.

And often I feel like that’s the way things kind of evolve when you’re doing movies. You know, you find the thing you like, and then you do it again, do it a bit differently, and then you say, “OK, I’m going to try a different thing here. I’ll go another direction.”

DEADLINE: You’re probably tired of talking about this, but there was a thing on the internet recently where people made TikToks in the style of your films. Were you flattered?

ANDERSON: Well, my experience of it is totally through people mentioning it to me. I’ve never watched them because I get too … I’m like … I don’t want … [Pauses] Not that it’s a criticism of somebody’s thing they’ve made, it’s like, do you really want to see somebody doing you? It’s like when somebody says, “Oh, so-and-so can really do you.” You know what I mean? Do you really want to see their imitation of you? It’ll make you…

DEADLINE: …Self-conscious?

ANDERSON: Yeah. “Is that what I do?” [Laughs] So I don’t look at them. I’ve never seen them. The only one I saw was The Ritz Hotel, which had done one. And I said, “Well, they owe me some rooms, if they’re doing my music and doing my moves.” But they never gave me any rooms.

DEADLINE: I’ll put that in the piece.

ANDERSON: [Laughs] I think they should be aware of it. I mean, I love The Ritz Hotel, but I do think they owe me some nights. But my main reaction is, well, it’s nice to have people getting inspired to do something from one of my movies. It’s fun, even if I would say, “Well, that’s not really how I would do it.” I mean, they’re doing their own thing.

DEADLINE: Moving forward, you’ve been working very quickly lately. You followed French Dispatch almost immediately with Asteroid City. Are you working on anything at the moment? Or are you taking a break?

ANDERSON: Well, before the Writer’s Guild strike began, we had just finished a script. Roman Coppola and I had been working on a script. So, when the time is right again, we’ve got a movie to make with Benicio Del Toro.

DEADLINE: And what’s it called?

ANDERSON: That I don’t want to say yet.

DEADLINE: Can you say anything about it, however cryptic?

ANDERSON: [Laughs] No, I don’t think so.

DEADLINE: How do you feel about the strike, and how do you see it going?

ANDERSON: Well, it’s so complicated. I mean, I have a slightly different point of view, because I’m old. I have some savings. But it feels like yesterday when I was experiencing the same vulnerability as many of the younger writers who [are striking]. I know that feeling — it’s so familiar — of anxiety and uncertainty. Their lives are completely led up to wanting to do this job, and suddenly they’re not finding a way to function.

But what can I say? I mean, I hope they figure this out soon because people are starting to enter into the direst straits, and they’re counting on being able to go forward. The leadership of these guilds have to find an answer. They’ve got to come together. Not that it depends on them, it’s just that, somehow, the deals have to get made.

DEADLINE: While the actors are on strike, is there anybody you have your eye on for when they get back to work? You have your own sort of rep company now. Is there any actor that you’d like to work with that you haven’t yet?

ANDERSON: Well, you know, we have Michael Cera. He’s one of the other characters in this new story. And he’s somebody I probably met, I think, close to 20 years ago. At least 18 years ago, something like that. I met him with Harvey Keitel, so it must have been 2008 or something. But, anyway, Michael Cera. That’s one.

DEADLINE: And the same question about music. Do you ever hear music and think, “That would have sounded great in a movie”?

ANDERSON: Yep.

DEADLINE: Is there a playlist in your head that you’re hoping to use?

ANDERSON: Well, first of all, usually I’m pretty focused on just my next thing I’m working on. Randall Poster, who’s worked with me for years doing music supervising, he and I often have had songs that we’ve set aside and come back to. We’ve had songs for years that we would say, “Somehow, we’re going to find a place for this one.” And we’ve used a lot of them up. But, yeah, I have a little bit of music and a sound for this next movie. That’s all I can say. It’s something that comes from movie soundtracks more than it comes from songs.

DEADLINE: You’ve had a pretty storied career. You’ve worked with lots of great people, had a lot of unusual shooting experiences. Is there anything you’d still like to do, or see, or achieve?

ANDERSON: To me, the big thing is to be able to keep making movies. It’s a great luxury to be able to make a movie where you can build things, and you have a big idea and just do it. I try to make my movies within a certain economy, so I don’t do huge-budget movies. I mean, The Life Aquatic was a great big production, and I learned from that that I feel I’m happier working in a more modest context. But not too modest. It is very fun to me to be able to keep it economical, but still to be able to do big things. I love building stuff for a movie. I love to stage a scene with actors in a thing that we’ve created, to give them a place to work in.

You know, when we were doing Asteroid City, the actors, each time they arrived, they would go into this desert that we created, and it was a wonderful place to film them coming to life. I want to be able to keep doing that. But there’s definitely plenty of room for variation. And the way that everything is evolving, who knows exactly where we’ll end up in five years’ time anyway. How does it all work? How is it sustainable? Obviously, the first thing is to figure out how to get everybody back to work.

Best of Deadline

SAG-AFTRA Interim Agreements: Full List Of Movies And TV Series

TV Cancellations Photo Gallery: Series Ending In 2023 & Beyond

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.