Explained: How changes to OSAP are affecting students in Ontario

As students begin to receive their estimates for the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP), many are attempting to understand what changes to the program will mean to them.

Although the cuts were originally announced in January by Doug Ford’s Ontario Progressive Conservative government, students applying for OSAP didn’t have the exact numbers, making it unclear how their funding might change.

A poll Yahoo Canada conducted on Facebook found 82 per cent of respondents disagreed with the changes to OSAP.

Here’s what you need to know about the policy changes, and how those changes have affected public post-secondary education in the province.

What policy changes were made?

In January 2019, Doug Ford’s government announced a new tuition framework that revised aspects of OSAP.

Grants introduced by the Liberal government in 2016, in which 185,000 students participated, were axed. Under Ford, grants would still be available for low-income families, but would not cover the entire cost of tuition.

Those from families with annual household incomes under $50,000 will receive 82 per cent of the grants available, but no student will receive grants that cover their entire education. If loans are required to cover the difference, those will have to be repaid.

Students from families with annual household incomes over $140,000 are no longer able to apply for grants, only loans.

Fees students pay when attending school are now optional, including club fees. Student-centred organizations will no longer have guaranteed funding from student fees.

On the impact on the institutions themselves, a new policy cuts tuition for students by 10 per cent. This reduces funding by two to four per cent for universities and colleges. The province will not replace that funding for the schools.

After graduation, the rules around paying loans back have also changed. Students now must pay their loans back once they start making $25,000 a year. The previous threshold was $35,000. The six-month grace period to pay back loans after graduation is also eliminated.

How have the changes impacted students?

Ontario students currently pay the highest tuition rates in the country. Students who have received their OSAP estimates this month say they are scrambling to find the funds to pay for fall tuition.

I am receiving HALF the amount of #OSAP funding that I received last year. I'm nearly in tears, as I worry about being able to afford school this year. So thank you @fordnation for making it nearly impossible to go to school and shaping our future for the worse. pic.twitter.com/5N8hJPu1k0

— Marianne (@Mariann84249936) June 18, 2019

But if tuition was cut by 10 per cent, why is this a problem?

These factors regarding the nature of OSAP mean a straight tuition cut doesn’t mean direct savings for students, says Neill.

“They get quite complicated,” she says. “It's unfortunate that these changes have made it harder to understand what [students are] getting”

Tuition may be cut by 10 per cent, but eliminating grants and increasing loans mean that many students are in fact paying more for school out of pocket.

As the total amount of money being handed out has been reduced, student debt burdens increase and impacts whether university graduates can access aspects of adult life, including home ownership.

But Neill says future university or college students shouldn’t overly worry, as the program is still fairly robust.

“Go onto the calculators and see what you're eligible for. These are changes that do reduce the generosity of the system but it's still a pretty decent system overall.Don't panic,” she says.

How much does university or college cost in 2019?

Tuition fees for university have risen dramatically over the last few decades in Canada. In 2016, students paid about 40 per cent more for tuition than they had 10 years prior.

The average undergrad student paid $6,373 for the 2016-2017 school year, which doesn’t include housing, textbooks, transportation and groceries.

A 2015 study from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives found that tuition and fees for students had tripled from 1993-1994 and is predicted to continue to rise.

One of the main reason tuition costs have continued to rise is that government no longer funds public universities the way it used to. In the mid-1970s, provincial governments were covering three-quarters of the costs of a university education. So if that’s when you went to school, you might consider yourself lucky.

Ottawa began cutting funding to schools in the 1990s, with the government’s share of funding falling to half of what it used to be.

But if students work summer jobs, can’t they cover tuition costs?

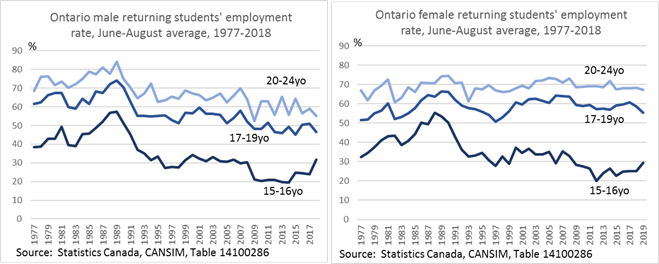

It was easier to find a summer job 30 years ago, and many more students are opting to study over the summer to keep up, says Neill.

“Almost no high school students were studying in the summer 30 years ago,” she says. That combination of studying and work which is the norm now may contribute to making less income.

If a student worked a minimum wage job for 40 hours a week, five days in the week during the summer periods, they would make less than $5000, which is not enough to cover tuition.

They would also have no money left for books, which are often several hundred dollars, or rent, transportation or food.

The Yconic/Abacus Data Survey of Canadian Millennials, conducted for the Globe and Mail, found that one-third of those 15-33 were working more than 30 hours a week at their latest summer job. They also found that 23 per cent worked 30 hours or less at a summer job, while the rest were working multiple part-time jobs or taking summer classes.

But that work doesn’t translate into enough money to cover schooling costs, as 49 per cent made between $1,000 and $5,000 at those jobs.

Attending a good school outside of their hometown could cost up to $20,000 per year with living costs. For those students who borrow money for their education, the average debt load is between $20,000 and $25,000 for a four-year undergraduate degree.