Why complacency and lifting restrictions could be driving India's high COVID-19 numbers

Megha Mogare, a chauffeur in Mumbai, has been out of work since March, when the Indian government introduced one of the world's strictest lockdowns in reaction to the coronavirus pandemic.

Mogare lives in the poor neighbourhood of Dharavi. Often described as one of Asia's largest slums, it is a labyrinth of small, cramped lanes and home to one million residents.

Earning just 15,000 rupees ($268 Cdn) a month before the pandemic struck, it was always a struggle for the 56-year-old to make ends meet, let alone build up enough savings to see him through a crisis.

"The situation now is so bad I can't run my own house," he said. "I've had to take out loans."

On Tuesday, India added 55,342 COVID-19 cases in 24 hours, bringing its total number of confirmed infections to 7.17 million, according to data from the country's Ministry of Health.

These daily new infections may be off their recent peaks and were the lowest numbers in almost two months, but India is the second worst-affected country after the United States, and it is set to have the largest caseload in a matter of weeks.

India's high number of new cases is being driven by the ongoing lifting of lockdown restrictions and complacency around following precautions to prevent the spread of the virus, epidemiologists say.

The country's deaths total 109,856, the data shows, compared to 214,768 deaths in the U.S. and 9,666 deaths in Canada, according to figures from Johns Hopkins.

A downward trend

Authorities are encouraged by the dip in new infections, however. The Health Ministry on Tuesday wrote on Twitter that "India is showing a trend of declining average daily cases over the past five weeks."

The lockdown in its first phase dictated that people could only leave the house for basic supplies or to carry out essential services, as authorities and medics feared the consequences of the spread of the virus in a country of more than 1.3 billion.

With a weak public health-care system, India needed to slow the spread of the virus by enforcing physical distancing, and the country needed time to prepare.

"This is a necessary step," Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in his address to the country as he announced the move in March. "The nation will have to certainly pay an economic cost because of this lockdown."

Restrictions have been steadily eased in recent months in an effort to revive livelihoods, but they have yet to be completely lifted, and the economy remains sluggish.

The central government has only this month given the nod for schools to gradually reopen, as well as cinemas — but not all states are permitting them to restart after they were shut in March.

'Jury is still out'

Meanwhile, critics have raised questions over whether the early lockdown paid off, particularly given that India is now adding more new infections on a daily basis than any other country.

"The jury is still out [on the success of the lockdown]," said Dr. Vispi Jokhi, CEO of Masina Hospital in Mumbai, which has been inundated with COVID-19 patients since the pandemic hit and has a waiting list for admissions.

Doctors in India say relaxed attitudes towards the virus are fuelling numbers. Many people do not wear masks in public, even though it is mandatory. The physical distancing that Modi has long said is paramount is frequently ignored.

"India has eased restrictions because the economy was suffering a lot because of the lockdown, but we haven't been able to inculcate that kind of discipline which makes people self-regulate to the extent that is required, and as a result the number of cases are increasing," said Jokhi.

Some doctors say the relaxed attitudes are partly because people see a low death rate and don't really feel afraid of the virus, along with general complacency.

Many humanitarian and medical experts agree that the government had little choice but to impose restrictions to try to manage the situation — but they now debate whether India has eased measures too quickly or whether it left them in place for too long.

Reopenings as cases rose

Jokhi said he believes the "restrictions were eased too fast," as metro rail services and shopping malls reopened as cases continued to soar.

Others disagree.

"I think the lockdown was very timely in the sense it was announced when the virus was beginning to become a threat and there was widespread fear it could go out of control," said Manu Gupta, the co-founder of SEEDS, a non-governmental organization in India that focuses on helping people cope with disasters.

India's lockdown was announced by Modi on March 24, just hours before it came into effect, causing widespread chaos and confusion.

Cities like Mumbai, the country's financial capital, virtually ground to a standstill.

The price paid by many has been high.

'Everything got shut down'

Daily wage labourers who live a hand-to-mouth existence were left stranded without work, and some of them resorted to walking hundreds of kilometres to return to their villages. Some of them reportedly died along the way as a result of road accidents or exhaustion.

"Overnight everything got shut down and I couldn't even leave," said Deepak Pawar, a migrant worker who relies on odd jobs on building sites in Mumbai to make a living. "There was no transport available."

Initially, the lockdown was in place for 21 days, but it was later extended, and over the past few months the government has been unlocking sections of the economy in phases.

"With hindsight, what didn't go well was that it got prolonged," said Gupta. "This meant that the secondary negative effects started to outweigh the positives achieved in the initial lockdown. Of course, the biggest casualty was the economy."

As migrant workers fled from cities to the villages, some took the virus with them, he said.

There were, however, some "remarkable" achievements in the first three weeks of the lockdown, Gupta said, such as the government launching a COVID-19 tracking app, which allows citizens to track infections around them and offers health advice.

Economic relief offered

But extended restrictions "created an unprecedented humanitarian crisis across the country ... and irreparable damage," Gupta said.

The government came out with economic relief packages to try to ease the pain, but critics said these did little to put cash in the hands of the poor and the benefits did not reach everyone.

"We didn't receive any help from the government," said Ravi Gavli, a labourer. "No sanitizers. No arrangements were made for us. We didn't have food either."

Millions of poor people in India are still feeling the brunt of the pandemic-induced lockdown.

Unemployment stood at 28.4 million in September, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a think-tank

The country's GDP slumped by 23.9 per cent in the quarter between April and June on the same period a year earlier, official data reveals, and analysts forecast a rare contraction for the financial year to the end of March.

Government defends lockdown

The Indian government has defended the lockdown, saying that numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths would have been far higher had it not done what it did, and it cites the country's ostensibly high recovery and low fatality rates, with an official recovery rate of 86.8 per cent and a fatality rate of 1.5 per cent.

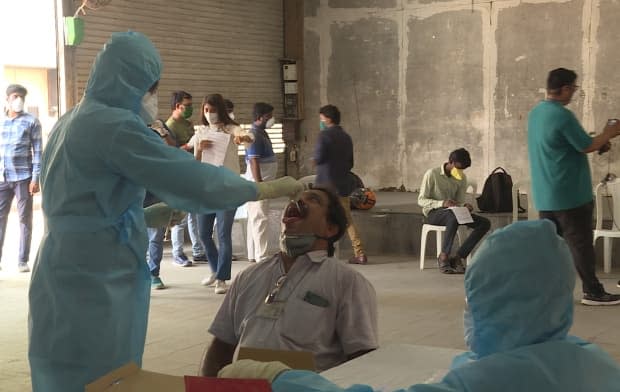

But medical experts point out that infections are still rising rapidly and that actual numbers are far higher than what is seen in official figures — partly because testing was very low in the early stages.

"I personally do not believe that India did the lockdown very effectively," said Dr. Swapneil Parikh, a Mumbai-based doctor who has a focus on lifestyle issues and has written a book about the coronavirus.

Parikh said that physical distancing during the lockdown was not strongly enough enforced and once restrictions were relaxed, many people completely ignored the necessary precautions.

"Right after, the milder, more persistent form of physical distancing didn't happen — because let's be realistic. In India, the ability to physically distance is a privilege for a small minority."

He said that it was always going to be a challenge to enforce physical distancing in a country where 10 people may share a tiny, single room home in a slum.

More COVID-19 facilities

"I think a lockdown is always meant to be temporary and it's always meant to be a stop-gap measure to scale your test, trace, isolate, support care — all your health capacities," Parikh said.

State governments did ramp up infrastructure during the lockdown, with cities including Mumbai and Delhi adding sprawling COVID-19 facilities with hundreds of beds.

Readying for a pandemic in the midst of its spread is no easy task, however.

"I don't think that it is a reasonable expectation to be able to scale pandemic response in a few short weeks when successive governments have failed to do so over several decades," said Parikh.

"We started with poor capacity to respond to this. COVID-19 is bringing Western countries to their knees, so this was an expected eventuality in India and it was not one that was adequately prepared for in the last several decades."

But the worst could be yet to come.

Some medical experts, including Parikh, fear that despite the recent dip in cases in India and some arguing that the curve may be flattening, there could be a surge to new record highs in the coming weeks as the country heads into its festive season, climaxing with the Hindu festival of Diwali next month.

This is a time when people traditionally travel and meet family and friends to celebrate, which could prompt another spike in cases.

Not everyone is in the mood for festivities this year, however.

"I don't have any hope," said Mogare. "It doesn't seem like I will get a job this year."