Why Does Gen Z Love Nirvana Tees, Thrasher Hoodies, and Bass Pro Shops Hats?

GQ; Getty Images, Backgrid

It’s Merch Week at GQ. Read The End of Merch, and check out our 41 Most Iconic Pieces From the Golden Age of Merch.

Costume designer Jordy Scheinberg noticed a trend on the set of You Are So Not Invited to My Bat Mitzvah, last summer’s charming Netflix family comedy that saw Adam Sandler play a pseudo-fictional dad to his real-life daughters, Sunny and Sadie. On camera, Scheinberg had dressed the film’s young cast in dialed-up, thematically considered versions of a contemporary Los Angeles tween’s wardrobe; in this case, that meant lots of fast-fashion party dresses and tie-dyed Online Ceramics T-shirts.

But whenever production wrapped for the day and the kids would gear up to go home, she clocked that they would all change into similar variations on the same outfit: pajama pants and a hot-pink Nirvana crewneck sweatshirt. The latter featured a rainbow-sherbet-toned version of the Seattle grunge band’s logo—a blissed-out, slack-tongue smiley face with Xs for eyes, first seen during the 1991 promotional cycle for the trio’s landmark sophomore album, Nevermind.

Given that all of these kids were born in the aughts, Scheinberg (a younger millennial, not even quite old enough to justify feeling truly possessive of Nirvana’s prime) felt confused. When she asked the kids if any of them listened to or liked any of Nirvana’s 30-year-old output and heard nos across the board, she felt totally vexed.

“Every single one of the kids—the boys, the girls, even some of the moms—had this sweatshirt,” the costume designer recalls, still reeling these many months later. In particular, the capitalism and Kurt Cobain of it all didn’t sit quite right. “It got to the point where I hated [this sweatshirt] so much that I had to lie and say that the legal team at Netflix wouldn't let me put it in the movie, because so many of the kids wanted to wear it. I was like, ‘Oh, we don't have the clearance for this band.’” As Scheinberg saw it, Gen Z regarded band shirts as little more than zesty—or even neutral—graphic tees.

As it turns out, this particular electric-pink Nirvana sweatshirt—which the cast members reported buying from Urban Outfitters, that mall-brand stalwart of alt-flavored garb, where it retails for $79—had already taken on a life of its own on TikTok. Across dozens of posts, users gleefully malign the pink sweatshirt wearers on their inability to name three to five Nirvana songs, while the pink sweatshirt wearers neg back with the purposely inflammatory no-thoughts-head-empty gag that Nirvana isn’t a band, it’s a clothing brand. Writer Sarah Stankorb detailed the phenomenon for Slate last fall, recounting her dismay to hear her young daughter describe her peers who wear Nirvana shirts as “preppy.” In other words, this pink Nevermind smiley sweatshirt is the band-merch equivalent of a Stanley cup.

“I would've been humiliated if somebody had asked me, ‘Oh, do you even like Nirvana? Name any song,’” says Scheinberg. “I would've clammed up because that's the culture I grew up in—like, you can't rep something unless you know something about it. And I feel like that does not exist anymore.”

Echoing Scheinberg, the writer Casey Lewis, who examines youth consumer trends in her popular newsletter “After School,” agrees that broadly manufactured merch has simply become part of a young person’s uniform.

When I pose the idea to Lewis, she wonders: “Have bands like Nirvana been flattened to the point where they're basically no different than a brand's logo?”

This week, GQ is considering the state of merch. We sourced a showcase of the coolest, most thoughtfully crafted pop-culture merchandise put to market in the last decade or so, relics made by and for 21st-century trendsetters, small-run society brands (including the aforementioned LA company Online Ceramics), enterprising multihyphenates, niche publications, and local eateries patronized by the martini-and-french-fries set. In his accompanying essay, my colleague Samuel Hine sounded the death knell for this particular milieu of merch that had come to define the last decade-plus of menswear—arguably nowhere more so than here at Gentleman’s Quarterly. We henceforth exalt and release these treasured, if heavily designed and increasingly plotty, hoodies and T-shirts that double as objets d’art and, as Hine writes, generally convey “a fuzzy bicoastal identity.” But what about their mass-produced counterparts?

As Hine concedes in his essay, merch as a consumer good—a pure money-moving product—is as booming as ever. Blockbuster tours by Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Harry Styles generated their own multimillion-dollar merch economies. Name a platform—Instagram, TikTok Shop, your nearest mall, or your local bodega—and there is a near-certain chance it will offer printed sweatshirts, tees, mugs, and other ephemera for sale. Procuring a piece of mass-produced merch with a licensed logo, such as a Nirvana sweatshirt, is about as uncomplicated as buying a Diet Coke or a box of tissues.

Indeed, you can buy a Nirvana band T-shirt for under $50 from almost any major apparel retailer you can think of: Urban Outfitters, Gap, H&M, Hot Topic, Target, Old Navy—hell, even Abercrombie & Fitch sells one. And it’s not all mass-market, either: In 2019, Marc Jacobs remixed the smiley-faced Nevermind tees in a redux capsule based on his storied “grunge” collection for Perry Ellis in 1992—around the same time Grace Coddington styled a then modern “Sliver” tee in the pages of Vogue—which ignited a series of lawsuits regarding the design’s usage. (The band’s company, Nirvana LLC, copyrighted the X-eyed smiley face in 1993, and its subsequent ubiquity has spurned many disputes about its true provenance.)

Despite Nirvana’s broad popularity 30 years ago, the omnipresence of its merch marks a sharp bent toward the mainstream for the band’s legacy—or, at least, the legacy of its graphic design. In 1993, Walmart wouldn’t stock physical albums of In Utero because of the album’s anatomically lurid artwork; nowadays, the retailer sells In Utero tees in nearly two dozen colors. While rare, true vintage Nirvana merch has its own thriving ecosystem, the widespread availability of cheap, new licensed stuff is appealing to consumers who were born years if not decades after Nevermind hit shelves. Whether or not they like the band is essentially besides the point.

Social media sociology tends to “typify” people by a shared personality—there’s always lots of talk about types of people, whose generalized personas are based on material points such as possessions, behaviors, or interests. A popular garment that becomes linked to a “type” of person can quickly turn into a meme-ified trend. A licensed Nirvana shirt is one, although there are other pieces of widely manufactured merch that stand out from the last several years, each with its own iconography that offers a tinge of counterculture, with all the comfort of monoculture.

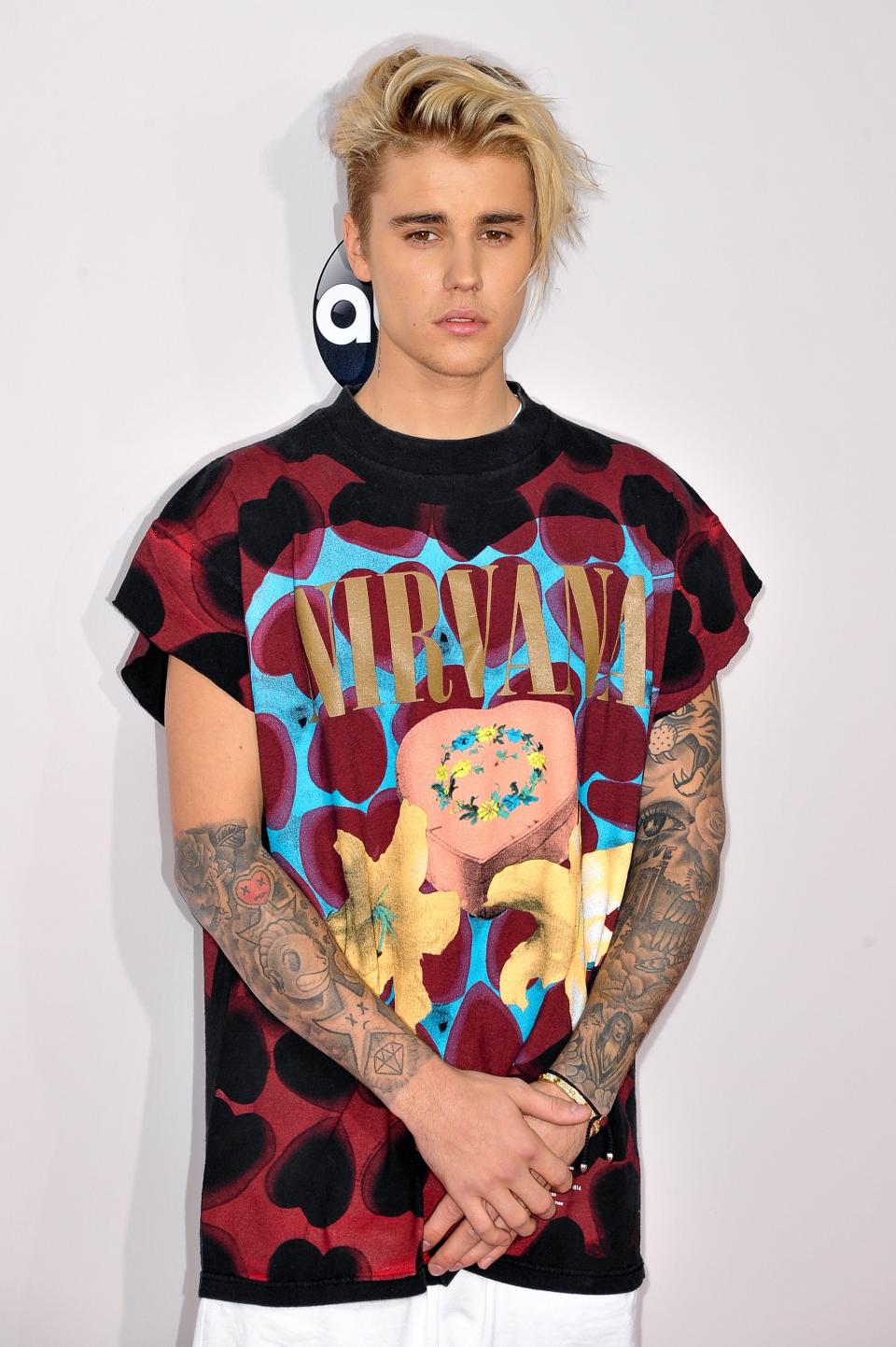

2015 American Music Awards - Arrivals

Demetrius Andrade v Luke Keeler - Weigh-In

Celebrity Sightings In New York - March 16, 2016

In the late 2010s, the branded Thrasher sweatshirt—a piece of memorabilia commemorating the 43-year-old California skateboarding magazine, whose logo featured a tilting, bright yellow typeface often bordered by cartoonish flames—was a boon to late-stage Tumblr users, ascendant Instagram-native nepo babies, and sartorially minded stars like Justin Bieber, Rihanna, Tyler, the Creator, and A$AP Rocky. In 2016, prototypical Gen Alpha celebrity North West, who was then two years old, wore a pint-size Thrasher tee while her parents accompanied her to Build-a-Bear at LA’s Westfield Mall. Unsurprisingly, the popularity of Thrasher merch among nonskaters didn’t thrill the skating community: “We don’t send boxes to Justin Bieber or Rihanna or those fucking clowns,” the magazine’s late editor Jake Phelps told Hypebeast in 2016, chiding the stars’ lack of skater bonafides. “The pavement is where the real shit is. Blood and scabs, does it get realer than that?”

Nonetheless, by 2017, Vogue had declared Thrasher tees an off-duty-model staple, and nowadays, Thrasher sells its wares on Amazon, where a hooded sweatshirt runs around $70, as well as at mall retailers like Zumiez and Pacsun. (An annual Thrasher subscription, which costs about $30, also comes with a free logo T-shirt. All told, probably not such a bad revenue stream for a traditional-media company.)

More recently, young consumers fixated on brightly hued polyester, mesh-backed logo trucker hats from Bass Pro Shops, a national sporting-goods chain that began in the early 1970s as a small fishing-tackle operation out of the Missouri Ozarks. The caps come in sporty colors like cobalt and blaze orange, and feature the brand’s red-and-goldenrod logo with an illustration of an agape spotted bass, and the stores have sold them for around $5.99 for years; as one TikTokker put it, the caps are “clean, timeless, and one of the only things other than the AriZona iced tea to beat inflation.” By the early days of the pandemic, TikTok was rife with “Bassholes,” and the caps were common among the platform’s most popular (usually male) creators: the countless proverbial sons of Sway House, the app’s since-disbanded bastion of lip-biting bad-boy influencers, at the height of their Saddle Ranch prowess. The professionally unlikable YouTuber turned prize-fighting boxer Jake Paul owned Bass Pro caps in several colors.

The Wall Street Journal attributed their popularity in part to the high-crown trucker hat’s nostalgic mid-aughts silhouette, and while Spy writer Jonathan Zavaleta zoned in on how the caps followed a wider, post-Trump “appropriation of blue-collar, middle-American sensibilities and workwear by cool teens and white-collar creatives,” such as John Deere merch, Carhartt double-knees, or RealTree camo.

For a certain kind of young consumer, the prevailing TikTok connotations all imply the same cynicisms: If you’re wearing a Nirvana shirt (and especially if you’re a girl), you probably can’t name five Nirvana songs. If you’re wearing a Thrasher hoodie, you’ve likely never set foot on a board. And if you’re wearing a Bass Pro hat, you’ve never seen a live trout in all your life. It’s an extension of what feels like a tale as old as time: cross-generational ire playing out on the battlefields of gate-kept band T-shirts.

The antidote to these hyper-online implications, though, is the hard reality that wearing culturally or temporally anachronistic merch simply because it looks cool is a time-honored tradition. It is also a sign that the internet is still capable of doing one of the best things it’s best at: introducing people to references outside of their usual scope, whether it’s the decades-old music of a band like Nirvana, or the high-physical-barrier-to-entry world of skateboarding, or the somewhat site-specific pastime of hunting and fishing.

Casey Lewis views this as the continued softening on the value proposition of authenticity about one’s identity-making interests, which remains a defining value and distress point among Generation X and millennials.

Looking back to her formative years in the ’90s and early 2000s, Lewis remembers the “shame associated with being a poser, where I think if you wore a band tee that you weren't actually a fan of, then people would call you a poser. I would see that play out in teen magazines, or you'd see it play out in movies.” Few insults stung worse. “But now [many] of the ‘trending aesthetics’ we see are kind of the definition of poser: cottagecore, fairycore. People are trying on these identities that they aren't, but there's no shame associated with it now.”

“Something about these days with micro-trends and TikTok, and you can try on different identities much easier,” Lewis says. “Now it's like you don't even have to wear that look to your high school to experiment with your style. You can literally just post a video of yourself on TikTok to see how it fits, how that look suits you.” Life is but a department store beauty floor of possibility—why wouldn’t you care for a spritz of eau de counterculture?

According to New York Times critic and longtime merch connoisseur Jon Caramanica, cross-generationally popular merch is merely a sign of the source material’s potency. “Whether it was Nirvana or Thrasher or whatever, they won. They formed a cultural identity that was so powerful that it outlasted the actual thing,” he says.

“I'm going to assume if you're wearing a Nirvana shirt in 2024 and you don't know the band, maybe you have a sense that they were edgy. Maybe you have a sense that they rebelled. Maybe you're trying to tell some part of that story,” Caramanica explains. “It's not that different, frankly, from kids of my generation wearing Ramones T-shirts. None of y'all saw the Ramones.” Not dissimilarly, in 2015, GQ asked Fear of God founder and heavy-duty vintage band-shirt collector Jerry Lorenzo if he thought someone ought to be a card-carrying fan in order to rock a Nirvana tee; he said no, if only because “having played a small role in Kanye’s Yeezus tour merch, I’m just excited to see people wear it.”

The potential for discovery outweighs the preciousness of hard-wrought fandom. “Out of a hundred kids who are under 20 wearing a Nirvana shirt, maybe five of them go research the band and they find something fascinating and get really into it,” says Caramanica. “That, to me, is far more interesting than being on the churlish end of things and being like, ‘You don't know In Utero.’”

Originally Appeared on GQ

More Great Style Stories From GQ

For Years, Sylvester Stallone Secretly Owned a Legendary Watch—Now It's Up for Sale

Take a Closer Look at Usher’s $5 Million Met Gala Watch

Barry Keoghan Doesn’t “Like the Idea of People Being Paid to Act”

Why Tailors Hate Skinny Suits

12 Years Later, Air Jordan Is Finally Re-Releasing a Legendary Olympic Sneaker

Not a subscriber? Join GQ to receive full access to GQ.com.