Why is the English language packed with nautical slang?

Britain’s Royal Navy boasted almost 800 ships at the peak of the Napoleonic Wars and employed hundreds of thousands of sailors. Painting by Nicolas Cammillier, 1809. (Pegli Maritime Museum)

By and large, I'm pretty even keeled, but I sometimes go a bit overboard when in hot pursuit of a linguistic loose end — in this case, how so much nautical jargon has managed to work its way into our everyday speech.

The English language is chock-a-block with words and idioms deriving from life at sea. Don't believe me? I've italicized every phrase in this article that originated among sailors.

Take my first sentence above. A versatile captain can navigate either by the wind or large of the wind. A vessel on an even keel (the centreline of its hull) sails steadily, without listing to either side. A rope whose end is left loose instead of being securely tied can foul up a ship's rigging or sails.

Newfoundlanders and Labradorians may be more likely than most to fathom the maritime origins of expressions like these thanks to our long local history of seafaring. Many of us still have at least a passing familiarity with the jibs, bows and sterns that feature in sayings like the cut of your jib, a shot across the bow and from stem to stern.

Seafaring idioms aren't restricted to seafaring cultures, though. They're in wide use everywhere English is spoken, from the American Midwest to the Australian Outback. So how did they become such a mainstay of our vocabulary?

Britannia rules the waves

English is an island language.

Nowhere in Britain is farther than a two-day horseback ride from the sea, and, while the ocean may once have isolated Britons from their neighbours on the European continent, it eventually became the artery connecting them to the rest of the world.

By the height of the Age of Sail in the early 1800s, the number of sailors in the Royal Navy was equivalent to about two per cent of the British male population.

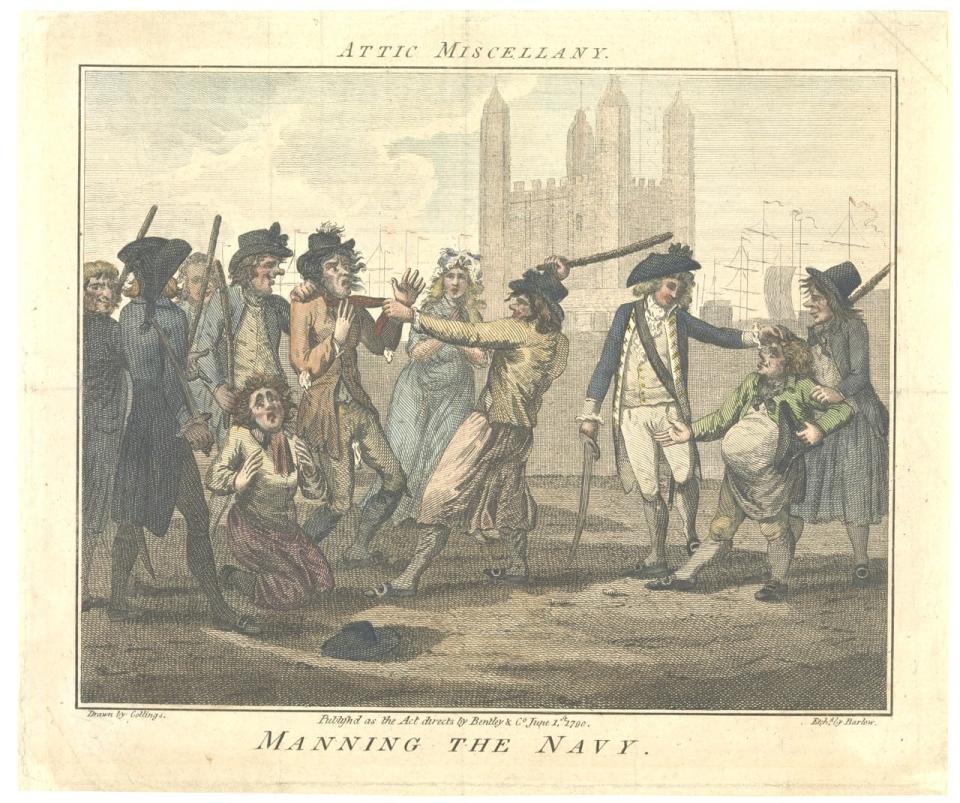

Many men signed on voluntarily, drawn by the promise of three square meals a day and a share of their ship's prize money. Others were pressed into service, kidnapped off the streets of port cities by press gangs and forced to enlist.

Naval service cut across the social hierarchy, bringing men from a wide range of classes into close quarters with one another. Seamen generally hailed from the working classes and officers from the professional and upper classes. Aboard ship, all had to learn a new way of speaking.

"Sailors' talk," wrote merchant seaman and nautical novelist W. Clark Russell in 1883, "is a dialect as distinct from ordinary English as Hindustani is, or Chinese."

At sea even familiar words took on new meanings, making the speech of sailors almost incomprehensible to landsmen.

Here, the devil was the longest seam in the hull, and when you were assigned to caulk it you had the devil to pay. The cat o' nine tails, the infamous instrument of punishment, was wielded only in the open air because below decks there wasn't enough room to swing a cat.

Besides navy men, merchant sailors and fishers, longshoremen and dock workers, coast dwellers, sailors' families, and anyone who travelled by sea would have been exposed to this Jackspeak — the lingo of British Jack Tars.

Sailors in popular culture

The large number of Britons in contact with sailors must have gone some way to popularizing seafaring jargon, but a second factor gave Jackspeak an even bigger boost.

The heyday of sailing happened to coincide with a boom in English literature. Over the course of the 18th century, newspaper and magazine publishing flourished, and the novel came into its own as a literary genre.

The romance and perils of life at sea provided rich source material for authors, and tales like Robinson Crusoe (1719), The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748), and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) were met with a groundswell of popular interest.

Authors peppered their prose with nautical terms to add realism to their work. For readers, the strangeness of the language seems to have been part of the appeal.

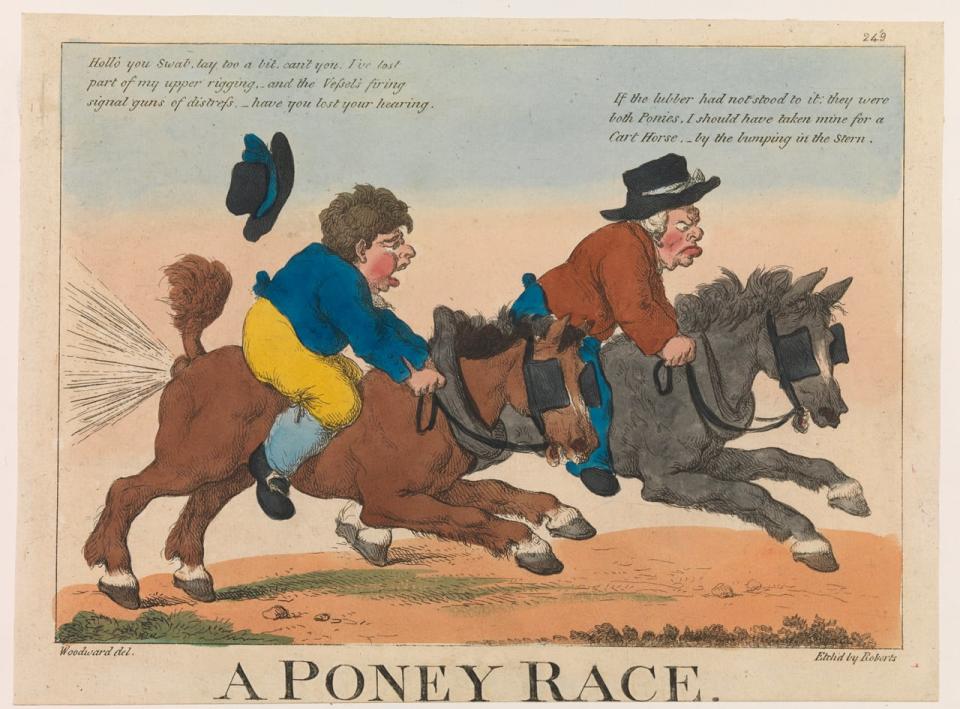

Jackspeak was like a riddle to be solved. It could hide thrilling racy undertones or dangerous criticism of authority. It could also be used to comedic effect, as it was in satirical cartoons of the day.

Cartoon sailors applied Jackspeak to anything and everything. Here, the man on the left is saying: 'Hollo, you Swab, lay to a bit, can’t you? I’ve lost part of my upper rigging, and the vessel’s firing signal guns of distress.' Etching by Piercy Roberts after George Murgatroyd Woodward, ca. 1775-1815. (Royal Museums Greenwich)

As nautical language became more recognizable ashore, it lent itself to metaphor. Landlubbers couldn't use the terms in their original context and so applied them to new situations.

A lifeline, originally a rope for sailors to hang onto in rough seas, became any type of help received at a critical moment. Leeway, the extent a ship drifted away from the wind, became any degree of freedom in time, space or action. A kink, or twist in a rope, became an eccentricity and, later, an unconventional sexual preference.

Today our language is laden with maritime imagery, a legacy of English's island origins and the appeal of a footloose life at sea.

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.