Why Teenage Rants and Fishy Witnesses Could Send This Man to Prison for Life

In the early morning hours of Oct. 11, 2017, Christopher Howard was asleep at home on Staten Island when his mother heard a banging at the door. Looking out her peephole, she saw the barrels of guns. It was the police.

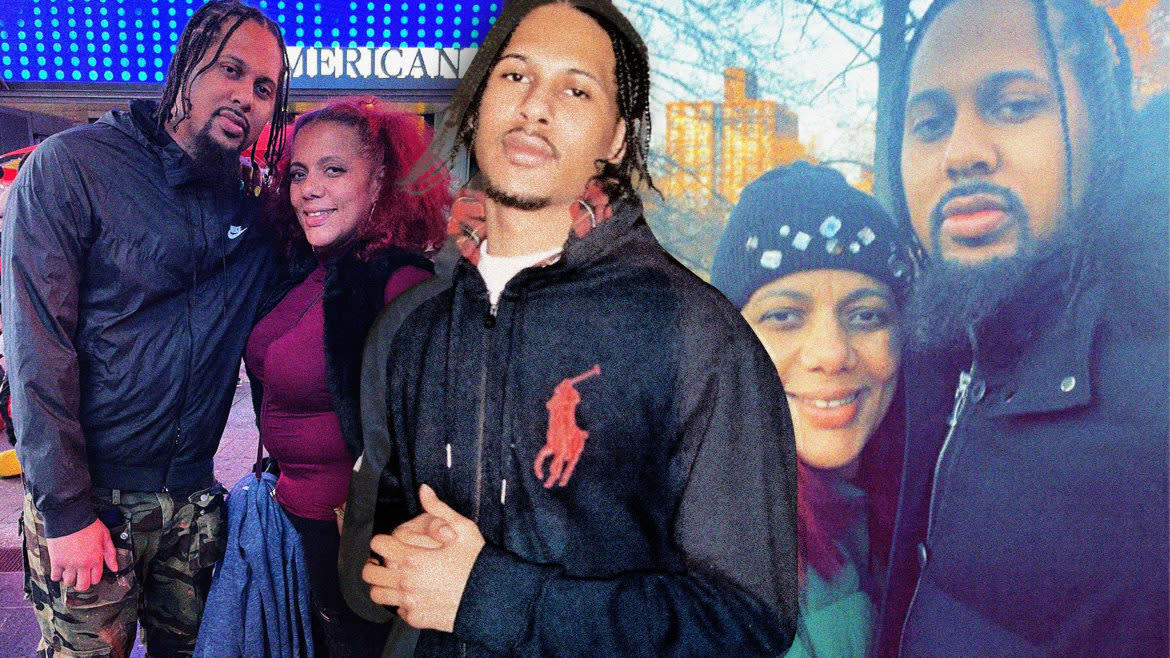

“They told me open the fucking door,” Kimberly Halliday told The Daily Beast. When she did, her apartment was raided by the FBI, who kicked down the door to her 25-year-old son’s room and arrested him.

“He was afraid,” she said. “I guess he was in the room asleep and you know, they just snatched him up and took them out.”

Later, federal investigators would announce a major takedown of Howard and 32 other alleged members of the rival MBG and Killbrook gangs who they said terrorized the Mill Brook Houses, a public housing project in the Bronx.

The death of 21-year-old Bolivia Beck, who was allegedly shot and killed by a Killbrook member, was highlighted.

At the time, murder rates were at record lows in New York City, but police had been ratcheting up their force and focus in one of the poorest urban areas in the United States, where they said violence continued to fester.

“The gang members we rounded up in this case, and in many other investigations, seem to not learn the lesson that they cannot act with impunity,” FBI Assistant Director-in-Charge William F. Sweeny Jr. said at the time.

The scale of the charges against Howard would soon come into clearer and more disturbing focus: He had been charged as a gang member under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO)—originally meant to take down organized crime like the mob—and accused of attempting to kill a man in a 2014 shooting at the Mill Brook Houses in which prosecutors say he missed his mark and instead injured his intended victim plus two others.

Police said Howard, who had no criminal history, had specifically carried out the shooting, firing into a crowded courtyard, to retaliate against Shadean Samuel, an alleged rival member of the Killbrook gang who sucker-punched Howard six years earlier when he was 19.

But Howard’s case has caught the attention of researchers and advocates who say it is emblematic of problems with the expanded use of RICO’s power to target poor men of color who have few resources to fight cases in which the law is on the government’s side.

It has also featured a set of extraordinary twists and turns—from a conviction by jury based on, among other things, teenage Facebook messages three years before the shooting, to a dramatic, but short-lived, taste of freedom.

Howard will finally learn his fate after a sentencing hearing later this month.

“I have a mandatory 10 years-plus for shooting, attempted murders,” he told The Daily Beast the night before he was set to be locked away for the second time. “With no gun, with no video, with no audio, with no geographical location with no anything—nothing … My whole case is off of hearsay and social media posts when I was a teenager.”

Professor Babe Howell of the CUNY School of Law is calling for a conviction integrity unit to review his case. But she and others say the question is not even whether or not Howard is guilty of a shooting. Rather, they argue, the case highlights how RICO statutes are being increasingly used to stretch thin evidence at trial and railroad men of color in impoverished communities in the name of public safety.

“I’ve been consistently stunned by the weakness of the evidence and the harsh penalties meted out to those who exercise their right to trial, while cooperators who have engaged in multiple acts of violence are rewarded with short sentences and released,” Howell wrote in a letter to the court supporting Howard.

Sealing a conviction

Howard says that the saga started when he was 19 and still living in the Mill Brook Houses in the South Bronx.

In the spring of 2011, he was sucker-punched by Samuel at a restaurant called The Chicken Spot.

“I got into an encounter in 2011 with some dudes or whatever from the other side of the neighborhood basically,” Howard told The Daily Beast. “One of the dudes basically sidelined me, punched me in my face … my jaw had got slightly fractured. And they used that because after that, you know, I was on Facebook speaking out of emotion.”

Howard was hospitalized, and the government entered into evidence Facebook messages which were read aloud by a witness at trial—including more than one in which Howard expressed his wish to kill the man. They used it to explain that his motive for the shooting was retaliation in order to grain cred in MGB—key to his prosecution under RICO.

“I want to murk that [sic]. Real shit.” one message said, according to a transcript of proceedings.

“What do you understand Juju,”—Howard’s nickname— “to be saying when he says, ‘I want to murk that N real shit?’” the prosecutor asked the witness, according to a transcript.

“He wanted to kill him,” said the witness.

Howard told The Daily Beast he was “like oh, when I catch the dudes, you know, I’m gonna do them dirty. You know, I’m gonna look for them. I’m gonna do all of this and, you know, I was saying a lot of crazy stuff, you know what I’m saying. I never said I did anything but I was just saying stuff out of emotion.”

These Facebook posts—along with a witness who gained immunity for testifying that he saw Howard carry out the shooting—amounted to the government’s direct evidence that Howard had committed the shooting three years after the sucker-punch. And that the act was part of warring gangs.

They also called multiple cooperating witnesses who attested to their own crimes, the two gangs’ violence, Howard’s membership in the MBG gang, and alleged instances in which Howard voiced dislike, or worse, for Samuel.

The witnesses, including Raynaldo Melendez—the government’s main witness, who attested to Howard firing the shots that sent three men to the hospital—had been offered immunity or cooperation deals.

At closing arguments in Howard’s trial, the prosecution said the evidence laid a clear roadmap to Howard’s guilt: “You know exactly who the shooter was. It was the defendant. And you know exactly why he did it, because the defendant is a member of MBG and because Scraps, the victim, the target, is a member of Killbrook who previously broke the defendant's jaw.” (Scraps was Samuel’s nickname; he did not testify in court.)

With this, the government was able to convince a jury not only that Howard had committed the crime, but also that he did it in order to advance his status in the gang—key in their ability to prosecute him under RICO statutes.

In her letter to the court, Professor Howell noted that the witnesses called against Howard had been offered immunity or cooperation deals despite admitting to, or being convicted of, dozens of violent acts.

Initially, Melendez, their main witness, told police he hadn’t seen the shooting. Later, he changed his story, according to a transcript of his testimony in court.

“There's nothing in it for me,” Melendez reasoned at the time, according to court transcripts. He said that by the time law enforcement came to see him as a 35-year-old in federal lockup, he hadn’t asked for the visit, but had decided that his “criminal thinking” no longer served him and it was time to tell the truth.

“Doing this time has really, like, really made me change my way of thinking,” Melendez told the court.

“All this is just so blatant,” protested Howard’s 75-year-old grandmother, Gail Halliday, in an interview with The Daily Beast in December. “It's just like anybody with a brain on that jury should have figured this one out that there was definitely room for... there had to be reasonable doubt.”

Representatives from the U.S. attorney’s office did not respond to requests for comment on these claims. But in 2021, Manhattan U.S. Attorney Damian Williams defended their use of RICO statutes in the case and explained that they were responding to increased shootings in Howard’s area of the South Bronx.

“We will use every tool available to hold accountable those who seek to hurt and kill their neighbors,” he told The Wall Street Journal at the time.

The paper also noted that the prosecution of the gang in Howard’s indictment had led to multiple convictions for shootings, including the murder of an innocent woman who had happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Conspiracy on steroids

In 1970, Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a law envisioned as a way to level the government’s power against the mafia and other deep-pocketed and highly organized crooks. The measure expanded prosecutors’ powers at trial and raised the penalty on what previously would have been considered independent acts.

Unlike a more traditional conspiracy case in which prosecutors must prove that someone had at least agreed to take part in a criminal act, a RICO conspiracy case is predicated on proving only that the defendant had agreed to be part of a legitimate criminal enterprise that had engaged in multiple criminal acts (Howard’s first count.)

“Conspiracy on steroids,” Howell told The Daily Beast.

And in order for Howard’s shooting and gun possession charges to be indicted under RICO, prosecutors had to prove that he did them in order to further his stance in the gang.

That first pillar, proving that Howard agreed with being part of MBG, factors into one of the more hotly debated elements of using RICO to go after gang members, experts explained.

“Hanging out with somebody is mere association that is woefully—that’s not evidence of anything,” said Martin Sabelli, former president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “And where you live in a ’hood, and you know, you could be in danger if you go outside of the hood. You know, how is that evidence of anything at all?”

In a RICO conspiracy indictment, prosecutors are not only able to group defendants together—but evidence as well. They can also enter evidence of past crimes of the defendant, as well as the crimes of their co-defendants.

“You’ve got all of these people. They’re all communicating with each other; they’re all childhood friends; they all grew up in the same neighborhood; they’ve all got all these connections,” prosecutor Jeff Grell told VICE following the RICO indictment of Young Thug and others in Atlanta. “You want to build up the [idea that this is a criminal] enterprise. And so it’s helpful, just circumstantially, to get a jury thinking, there’s all of these people, they’re all interconnected, and it’s all coordinated criminal activity.”

He added: “That’s one reason why prosecutors like to use RICO: It does enable you to paint a much bigger picture. Depending upon your point of view, some people are going to say it’s a more truthful picture to present it this way. A defense attorney is going to say, ‘No, I don’t want you to focus on this whole big umbrella. I just want you to focus on my guy, or my gal. Maybe they screwed up, but they’re not part of this enterprise. And they shouldn’t be found guilty just because they went to junior high with somebody.”

Since it was created, prosecutors have continued to expand the use of RICO to indict protesters to police departments and even top figures at the soccer giant FIFA.

In New York and other cities, the government has also leaned into leveraging its powers, along with conspiracy charges, to ratchet up their offensive on local street gangs and stamp out gun violence, which has increasingly plagued cities since the pandemic.

“RICO provides really powerful tools for prosecutors, not only to enhance punishments, but also to obtain discovery, and allows prosecutors to cast an extremely wide net in particular, particularly where it’s used in its current form of conspiracy,” said Sabelli.

No matter his guilt or innocence in the shooting at the center of the case, Howard’s ordeal has been, in many ways, extraordinary. Firstly, in that he went to trial at all.

Sentences under RICO conspiracy charges can hold longer minimum sentences—and are required to be taken consecutively—effectively pushing defendants to avoid what has been called the “trial penalty.”

“In federal court, 98.3 percent of cases end up in a plea,” said Sabelli.

But Howard, stubbornly, refused the government’s offers.

“I didn’t want take a plea deal because I felt like I did nothing wrong,” Howard told The Daily Beast.

Because of this, the now 30-year-old has become a ping-pong ball in a public struggle over the evidence in his case. Howard has gone from being convicted by a jury to being released from jail after he was acquitted of his top two counts to being thrown back in jail—and after all that, he now faces life in prison.

“I think this is just inhumane," he told The Daily Beast.

Howard’s case took a unique turn when the judge who presided over his initial trial in 2019 passed away. The new judge who took up his case did something extraordinary: She overturned his charges.

In her shocking ruling, Judge Analisa Torres said that, despite the jury’s previous finding, the government had not proven that Howard shot Samuel in order to become a bigger, badder member of the gang, noting that even fellow MBG members—government witnesses—had attested at trial to his lack of involvement in any violence or drug sales.

“There is nothing in the record between the time Howard made those [Facebook] statements and the night of the Shooting—a gap of more than three years—to indicate that Howard had any desire to gain status in MBG,” read the 38-page decision.

Whiplash

Howard was released on time served and spent nearly two years working with UPS and in medical transportation. He also spent time with his daughter, he said, taking the 3-year-old to the park and to the aquarium, he told The Daily Beast.

But nearly two years later, he found out that Torres’ decision was reversed on appeal by a three-judge panel who found the decision “erroneous.” He was later required to turn himself back into custody. Howard’s sentencing is due at the end of February, and meanwhile, he is being held at the notoriously brutal Rikers Island jail complex, where his mom says he has started to lose his hair and endured repeated lockdowns.

When he found out he was going back in, Howard said the whiplash was “horrible.” He felt he had been set up to lose.

“My grandmother cried, my mother done cried… they’ve been going through this with me for years. I’m still fighting this,” he told The Daily Beast, later adding, “My daughter, you know, she’s still a baby, so I’m hurt to even see my daughter right now. Knowing that I have to be remanded tomorrow, how can I go and give my daughter a hug to leave my daughter again?”

Howell, who is teaching the case to her class at CUNY, requested in her letter to the court that the U.S. Attorney’s Office release Howard pending sentencing and “create a conviction and sentencing integrity review unit and review these cases for viable claims of innocence, cases which should not have been tried due to lack of hard corroborating evidence, and for excessive and disproportionate sentences.”

“It appears that when you deal with the federal government and a RICO case, they don’t care,” said Howard’s grandmother Gail Halliday, who is fighting with his mother for Howard’s case to be reversed—again—and for a lenient sentence.

They described Howard as an easy, good son who had earned entrance into good schools through grades and had grown up socializing with those in his community and building—a tough neighborhood where it was difficult to avoid associating with those who got into trouble.

”Innocent, innocent,” repeated Halliday. “But they’re gonna say you’re guilty and that’s it: go to jail.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.