Wichita High School East turns 100: ‘History walks our halls’

Can you imagine a teacher today throwing a chalkboard eraser at a student for not paying attention in class?

Or a coach buying his high school sports team beer and cigars because they won a tournament?

How about a school making its boys swim naked in their gym class?

Such stories are part of the lore of Wichita High School East, the city’s oldest high school, along with the more serious legacy of educating generations of Wichitans.

East is celebrating a big anniversary next month. Though it opened as Wichita High School in 1873, the anniversary celebrates the 100th year the school opened in its current building at Douglas and Grove.

“They called it the million dollar school at that time,” said current principal Sara Richardson of the school’s cost, which was $1,044,810.85.

Due to the money, innovation and modified Collegiate Gothic style, Richardson said, “It was like the showcase of the Midwest.”

The importance of East to all of Wichita remains, she said.

“Anyone can find a tie back to East High in some fashion. . . . There’s just such a prideful thing for those who come from here that I think is uncommon. I think it’s tied to the history. I think it’s tied to the size. I think it’s tied to the backbone of the city.”

Indeed, a lot of leading business people came from East, such as billionaire Philip Anschutz, aviator Clay Lacy and former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates.

Oilman Dave Murfin has been known to say he learned his negotiating skills in the boys bathrooms at East, where it took smooth talking to escape with your lunch money and without a fight.

Numerous athletes also came from East, including Jim Ryun, the first to run a mile in under four minutes in high school; Wichita State football star Linwood Sexton; and Marilynn Smith, the LPGA co-founder and golf champion.

There are 100 banners recognizing notable graduates from each year hanging throughout the school for the anniversary celebration. There also are 100 historical facts pasted to the floors of the school’s hallways.

There will be a homecoming football game, parade and block party along with other festivities Oct. 6 and 7 ahead of the official Oct. 8 anniversary. Check out www.usd259.org/east for details.

Back to school for former East students

Lots of East students have returned to the school to work, including 32 current staff members, which is almost 17% of the staff.

“This old girl and I have been through a lot together,” said Darham Rogers, a ’99 grad who has taught history at the school for 17 years.

Rogers said when he returned, he was stunned to realize the floors still creaked — “a unique sound that I remember from back in the day” — and said he heard they creaked from the day the school opened.

Some things had changed, though, like the old gym had been demolished.

“It used to shake,” Rogers said. “I’m surprised it . . . didn’t collapse in on itself.”

He said the school has evolved and adapted for better and for worse.

“But that’s part of life. That’s part of the whole history of this amazing little school that we have here.”

Rogers does not mean little literally, because the school is anything but small.

It’s the largest high school in the state and has seen almost 59,000 graduates since it opened. At one time, it had 3,324 students. Today, it has 2,343.

Former students tell of such crowded conditions, girls would have to hold their short skirts to keep them from rising as they squeezed up and down the stairs.

School’s architecture adds college atmosphere

When you think of Gothic archways with lacework tracery forming a cloister, you might think of a prestigious hall of learning at Oxford — not a Wichita high school. However, those are just some of the architectural features East has.

“That gave the whole place an atmosphere of college,” said architect Dean Bradley, class of ’69.

Though he liked some of those elements as a student, he said, “I appreciate them more now than I even did then.”

Bradley said he remembers the school’s oak woodwork, which was stained a distinctive green instead of a more traditional brown or orange hue. Some of it is still visible, such as on a bookshelf in the library.

An August 1922 article in Wichita’s Plaindealer newspaper said the school building “departs sufficiently from the perfectly-balanced, symmetrical building to avoid the so-called ‘factory’ appearance and make it attractive and interesting.”

It added that “Wichita has reason to be proud of her achievement.”

East initially had a main building, a gym and some shops out back. Roosevelt Junior High was just to the west, and in 1990, it became part of East.

The school’s distinguished International Baccalaureate program is spread over the main building and former junior high.

Vocational buildings were added over the years, and eventually what today is known as WSU Tech began operating there.

Portable buildings accommodated East students when enrollment was particularly large before Wichita High School West opened in 1953 and Wichita High School Southeast opened in 1957.

When Wichita High School North opened in 1929, that’s when Wichita High School added East to its name.

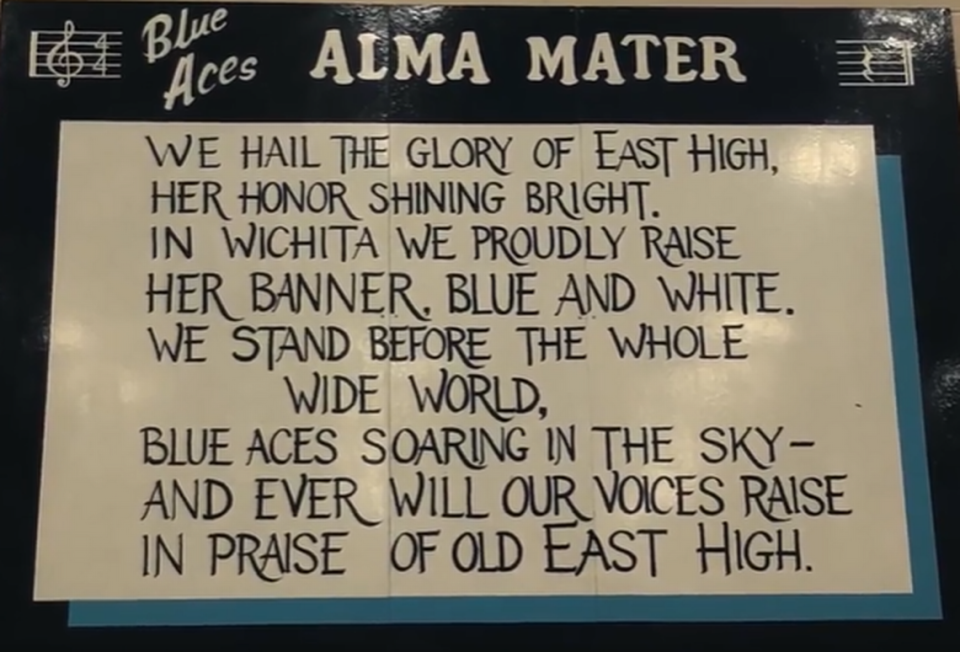

Just before then, the school voted to change its mascot from the Bulldogs to the Blue Aces.

It was a reference to the pilots in World War I along with a burgeoning new field in Wichita, Richardson said,

“It was a homage to the aviation industry.”

Heart of the school

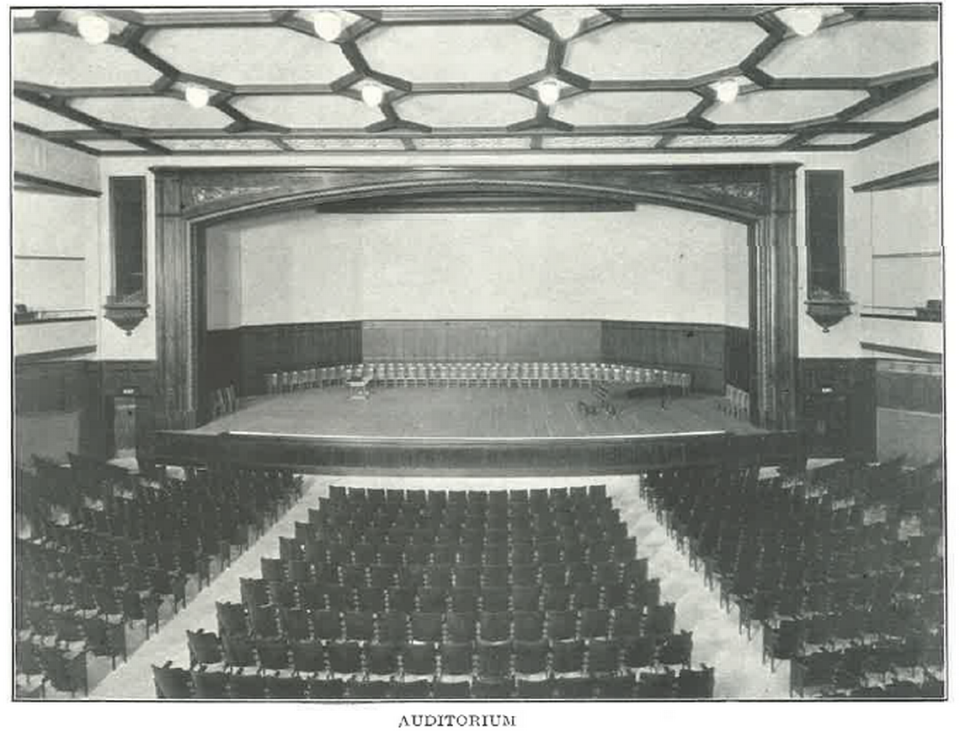

Through the years, the heart of East has been the school’s auditorium with its Tudor-style proscenium and seating for 2,200. Skylights let in a bit of light — and unwanted water when it rains — and stained glass windows grace its second floor.

Along with a pipe organ, The Eagle reported in October 1925, there was “a booth for a moving picture machine in the auditorium.”

The Wichita Symphony Orchestra once made the auditorium its home. Poet Maya Angelou spoke there in the 1990s. And something especially dramatic happened there on Dec. 8, 1941.

Steve Witherspoon, who taught social studies at East for 25 years, said his uncle, Bob Witherspoon, was a student there when Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941.

His uncle recalled that on the Monday after the Sunday attack, the school gathered students to listen to President Roosevelt give “his famous speech — the Day of Infamy speech.”

After, his uncle said a lot of students hugged, and some of the boys went straight to recruiting offices to enlist.

Ken Thiessen, who was principal of East for 16 of his 26 years at the school before retiring in 2018, said he heard that story, too. He doesn’t know if any students went straight out to sign up, but he said there were boys who became soldiers and didn’t get to finish school before enlisting. They were welcomed back to finish after their service, and Thiessen said the veterans were the only students allowed to smoke out back by a smokestack.

Similar to the Pearl Harbor memory, Thiessen said at reunions for classes in the 1960s, “a lot of those classmates clearly remember where they were in the building when JFK was shot.”

Each year, Rogers takes his classes on a historical tour right in the building.

There are walls of old trophies. There’s a plaque commemorating the school’s late veterans. And there are class photos that reveal how more and more people of color began attending the school in the 1950s and ’60s.

The tours “allowed them to kind of live the history a little bit,” Rogers said.

“History walks our halls.”

Shared memories, longtime traditions

There are all kinds of East traditions that have remained through the decades. Pranks on the principals. Senior parking. Different building corners for students of different grades to hang out in. An old lantern that hangs outside that runners tap on their way back from practice.

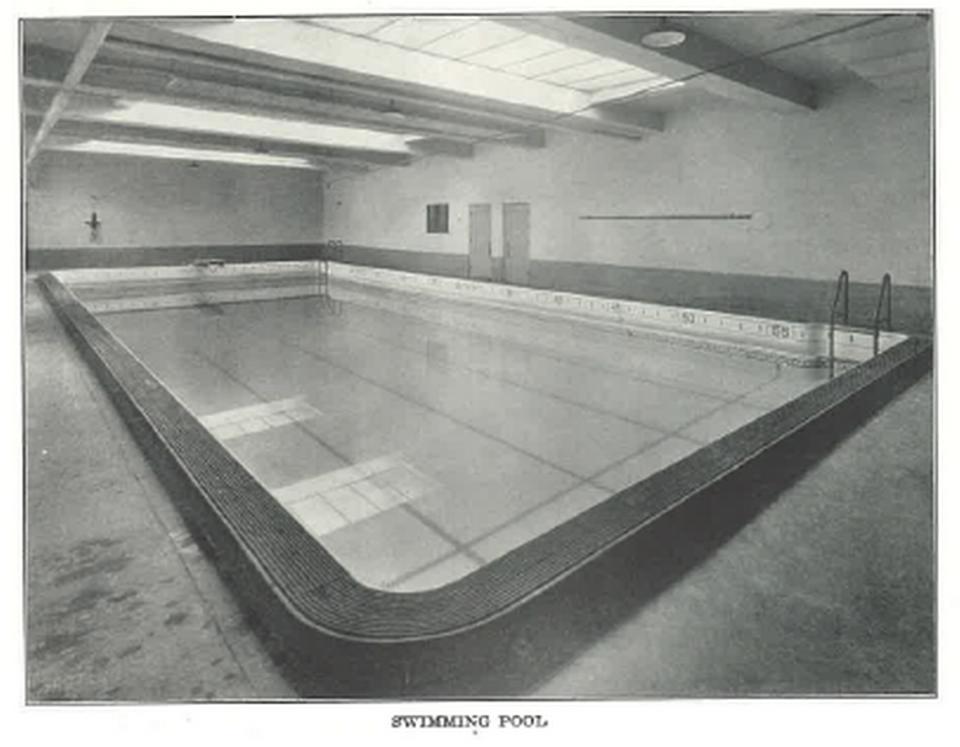

Then there are memories such as the old swimming pool.

“It was a pretty disgusting thing,” said Brian Rhodes, a ’73 grad who is in aviation marketing. “It looked like a bad, dirty bathtub with a shimmering scum across the top of it.”

Except it apparently was clean because of an overabundance of chlorine.

“It would burn your eyes just walking around the room,” Rhodes said. “God forbid you’d open your eyes under water. . . . It was like chemical poisoning of your corneas.”

It may be a little hard to believe, but some guys sometimes had to go without bathing suits. They have varying memories as to why — the school didn’t want wet suits mildewing in lockers, or the class allowed only particular kinds of suits — but they all seem to remember it was sometimes the case.

“Everybody has shared that with their kids or grandkids,” Rhodes said.

The girls didn’t fare much better. They had to wear the school’s wool one-piece bathing suits that their classmates wore days and possibly even decades before them.

“You get them wet, and they weigh 20 pounds, and then of course they start sagging everywhere — and I mean everywhere,” Rhodes said.

Everyone of a certain age seems to have a story about partying in College Hill Park, a regular hangout for East kids.

Buster Fairleigh of Buster’s Burger Joint, who also is a ’73 graduate, said his class is the reason there’s no overnight parking at the park anymore, “which at my age now I completely understand.”

The city put up signs stating what hours the kids could be there.

“The first two times they put them up . . . we tore them out of the ground because they couldn’t give you a ticket if the sign wasn’t there.”

The signs wound up in the College Hill pool.

Then the city had the signs put in cement.

Students went to the City Council to protest, but it was to no avail, Rhodes said, despite that they “did it very formally and properly.”

Speaking of partying . . .

Have you ever seen “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” or “Dazed and Confused”?

East “was somewhere in between,” said Don Guidas, ’73, of iHeart Media-Wichita.

“East High was an interesting combination of good kids, athletes, stoners, would-be hippies . . . loners.”

He said there still was some racial tension left from the ’60s, and there were “fairly significant fights that were eye-opening for a little sophomore like me.”

That was back when East was for sophomores, juniors and seniors only. Today, freshmen attend as well.

Along with fights, there was a lot of fun — too much fun.

“People were coming and going kind of as they pleased,” Guidas said. “I don’t mean that it was complete, total chaos, but it sure wasn’t tough to head out to your Volkswagen Beetle and hop over to College Hill Park for an hour or two.”

East English Street was a popular spot as well.

The school didn’t enforce skipping as much, Fairleigh said.

Jim Hill, another ’73 grad, said missing first hour “just became an unspoken thing,” and he and his buddies would head to the Pancake House on Kellogg.

Brownie’s, a nearby Valentine diner, was a popular spot for 99-cent hash browns while skipping class.

The Embers Lounge at Central and Lorraine was a hot spot as well. Fairleigh remembers the business opening at 6 a.m. for students on Senior Day.

There were “literally 50 kids up there having a few beers before we go back for Senior Day,” he said. “Can you imagine that happening today?”

Another hard-to-believe scenario happened when Rhodes joined the gymnastics team to keep in shape during the baseball off season. His assistant baseball coach was the gymnastics coach.

Once, at a tournament in Medicine Lodge, Rhodes said, “He goes, ‘Look, if you guys can do this, step up and win this thing, I’ll buy beer and cigars for the trip home.’ . . . He knew what helped motivate younger guys.”

The team won, so the coach stopped the team’s station wagon and bought what he promised.

“The best part of the story was him starting the car and emphatically telling us that we could not open the beers until we were well on our way out of town, while at the exact same time he was met with a perfectly timed choir of beers opening in unison without pause.”

Pranksters from years past

Much frivolity happened within the school doors, too.

Sheldon Lawrence, class of ’58, remembers several seniors from his class putting a Model A car on a large elevator and depositing it on the school’s second floor.

He said telephone poles used to lie on the ground to denote parking spaces, and sometimes, teachers “who drove small cars would find their cars straddled on one of the telephone poles.”

Murfin, class of ’70, said his father graduated from East in 1938, and his mother was a year or two behind him.

“Dad used to talk about the pranks they would pull. . . . And he halfway encouraged me to do that — and that’s another story I might leave out.”

Murfin is who shared about his economics teacher throwing erasers at students — never him — who weren’t paying attention.

“Everybody loved it. It was good. It was not a bad thing.”

Murfin is careful not to deride his alma mater in any way, although he said “it pains me immensely to see the school locked down the way it is now.”

Only one entrance is open at the school now, and there’s a metal detector.

“We had to make some hard choices,” said Rogers, the history teacher.

He said some things have gone away for the better, such as the toga dance and the Mr. Ace beauty pageant, where guys dressed up in women’s clothing.

What’s remained, Rogers said, is “a little bit of a mystique when you come into this building.”

“East High is bigger than any one person or any thing.”

Murfin said he “can’t say enough good about the school and the experiences I had and what I learned.”

Former radio personality John “Boy” Speer, who also used to teach in Valley Center and was mayor of Kechi, graduated in 1970 and said the school was pretty well integrated by then, for which he said he’s thankful. He said he has friends of all ethnicities because of it.

“We are lifetime friends.”

Fairleigh said he has more than two dozen close friends from his East days half a century ago.

“My kids don’t understand it.”

Guidas said that “East has come such a long, long way in the last 50 years. It’s really kept pace with the times. I’m really blown away.”

It was pretty great when he attended, too, he said.

“I’m incredibly proud to say I came from there.”