‘It’s wiping our youth out.’ How fentanyl has killed hundreds in the Kansas City area

Editor's note: Viewing this story in our app? Click here for a better experience on our website.

On a mid-September night two years ago, three friends from Johnson County sat in front of their school laptops and connected through an online video chat program.

From each of their homes, they took the drug they had purchased for 30 bucks a pill. Soon, one of them, a gregarious red-headed senior at Shawnee Mission East High School, began to rock back and forth. Her friends sensed she wasn’t feeling well.

Try to vomit, one of them told her.

The next morning, their friend was found dead. And yet another family and community was left to grieve what fentanyl had taken away. A young life full of promise, an aspiring model who competed on her school’s cross country team and dreamed of moving to California.

This kind of devastating loss has been repeated across the Kansas City area in the past five years, as some communities — on both sides of the state line — have had more deaths from the synthetic opioid than homicides and traffic crashes, The Star has found.

From 2018 through 2022, fentanyl has killed more than 850 people in the nine-county Kansas City region, according to medical examiner records obtained through open record requests. In Johnson County alone, there were 149 fentanyl-related deaths in that five-year period, which was triple the number of homicides in the county during that time.

“We are in a crisis. And I am afraid that we are at the front end of a tidal wave,” said Tony Mattivi, director of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, whose agency is part of a new team of law enforcement officers created to fight fentanyl. “I’m very concerned, with the way the numbers keep going up, that it’s going to get much worse before it gets better.”

In an ongoing investigation, we’re exposing the toll fentanyl has taken on our community. Initially, we focused on the youngest victims among us, and how dozens of babies and toddlers have died in the past three years after exposure to the drug inside homes, hotel rooms and even in a city park.

This report delves into the broader trail of destruction the crisis has left behind. How it has spared no age, race, gender, or geographic and socioeconomic background.

In other words: No one is safe.

“It’s not discriminating against anybody,” said Gabrielle Anderson, whose 17-year-old son died from fentanyl earlier this year in Blue Springs. “It’s gonna be everywhere, anywhere. I don’t care if you have a million dollars or a dollar, it can still get to you.”

Lori Smith, of Independence, lost her 37-year-old son, Matthew, last year. As she put it: “This is affecting every person in America. If not your child, it’s going to be someone you know.”

Indeed, in cities across the nation, police confront a skyrocketing number of deaths from a drug unlike any they’ve ever battled. The potency of fentanyl — 100 times stronger than morphine and 50 times more than heroin — has overwhelmed medical examiners, devastated families and frustrated prosecutors who often don’t have enough evidence to file charges after a death.

Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

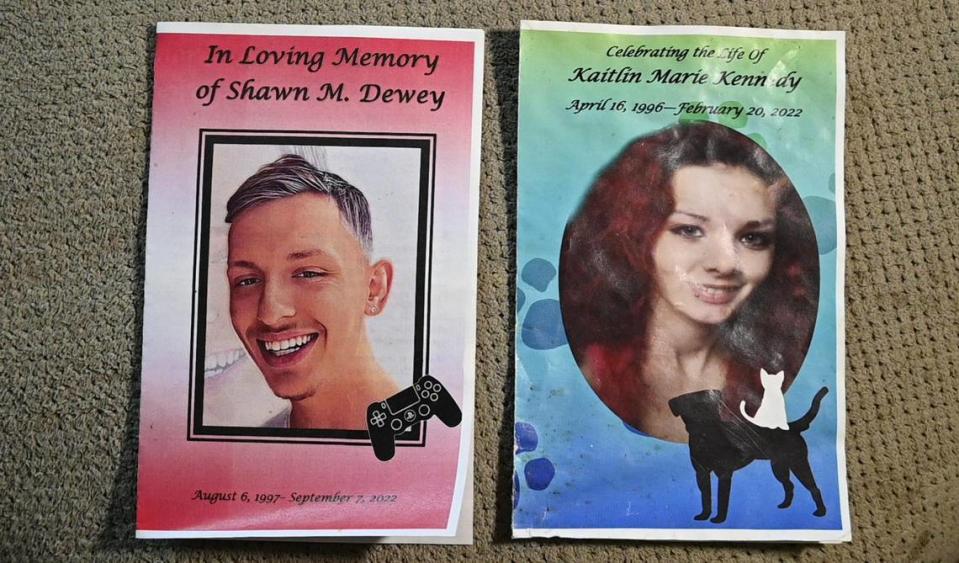

“It’s wiping our youth out,” said Shannon Earnshaw, whose son, Shawn Dewey II, of Edwardsville, died in September 2022.

Through months of reporting and talking to more than 100 people about this deadly drug, The Star has learned this: Fentanyl is not a problem for just police or prosecutors or even public health officials to solve alone. It’s a crisis that will take an effort from everyone to keep people of all ages from dying.

Sandy Clutter, of Belton, knows this to be true. So do many in her Cass County town.

Three teens from that area died from fentanyl last year. The first one in January and the other two in September.

“It brought the community to their knees,” said Clutter, executive director of Belton Cares, a Missouri Department of Mental Health coalition working with First Call and community sectors to affect positive change for youth in the city. “These kids did not take this drug trying to die. They were not trying to commit suicide. They were kids being kids and making poor choices.”

Belton Cares held its first town hall about fentanyl on Nov. 1 of last year — just weeks after those last two young people died. Since then the group and community have held many more meetings and candlelight vigils, taught residents about Narcan, a medication that reverses the effects of fentanyl, and trained them how to use it.

More events are planned for later this month to continue educating kids and parents about fentanyl.

“We’re in a war right now,” said Clutter, a retired school administrator. “And the battle is real.”

During the next few weeks, The Star will publish stories that detail how fentanyl has engulfed local law enforcement with cases, many of which never end up on prosecutors’ desks for possible charges. And we’ll show how one police department decided early on to attack the drug in a new way.

We also will take what we learn from our reporting into the community, hosting events and distributing literature and Narcan with the purpose of further explaining the devastation the drug has caused.

And ultimately, we hope to teach people what they can do if it reaches their families.

To use Narcan Nasal Spray for an opioid overdose, follow these steps:

Check for signs of an opioid overdose: 1. Unresponsive to touch or voice.

2. Slow, irregular or stopped breathing. 3. Constricted pupils. 4. Cold skin

Tilt the person’s head back and provide support under the neck with your hand.

Unpack the nasal spray. Hold it with thumb at the bottom of plunger and index/middle fingers on nozzle. Do not press or prime plunger.

1. Insert nozzle into one nostril. 2. Press plunger firmly to deliver dose. 3. Remove nozzle from nostril.

Seek emergency medical assistance right away. Move the person onto their side with legs bent and head on arms. If unresponsive after 2-3 minutes, use new Narcan spray in other nostril. Several doses may be required before the person revives, depending on the amount of opioids in their system.

‘My daughter didn’t ask to be murdered’

Fentanyl is a different kind of beast. More addictive. More deadly. In fact, a small artificial sweetener packet filled with the synthetic opioid would hold enough to kill about 500 people.

It’s becoming more prevalent across this area.

“Drug dealers are actually handing out Narcan to their buyers and saying, ‘Hey, make sure you have someone with you because this is the good stuff,’” said Clay County Sheriff Will Akin. “Drug users are literally saying, ‘Awesome, man.’ … It just seems so twisted to me now.”

An artificial sweetener packet contains about 1,000 mg of sweetener.

Whereas, a lethal dose of fentanyl is roughly 2 mg.

So, if one sweetener-sized packet contained pure fentanyl, that would be about 500 deadly doses.

In Kansas City, just one seizure last year netted enough fentanyl to potentially kill more than 5 million people. And the bodies continue to pile up in 2023 across the area as low-level dealers regularly remain on the street, the Star investigation found.

Solutions exist on how to save lives and have shown their value in several communities. Experts say Narcan should be as commonplace in homes as fire extinguishers.

But not all towns have been proactive. At least one — where six people have died from fentanyl just this year — hasn’t required police to carry Narcan. Yet.

So many of those who have died in the Kansas City area didn’t know they were taking fentanyl. Sometimes they thought it was a pain pill or anti-anxiety medication. Other times, drugs such as heroin, meth or cocaine were believed to be laced with the powerful synthetic opioid.

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, laboratory testing indicates 7 out of every 10 pills seized by the agency contain a lethal dose of fentanyl, an increase from 4 out of 10 in 2021.

And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fentanyl overdose is now the leading cause of death nationwide among Americans between the ages of 18 and 45 — more than car crashes, gun violence or suicide.

To those in our area who have lost their children to fentanyl, the deaths aren’t overdoses. They feel their sons and daughters were poisoned.

“They are being murdered,” said Dewey’s aunt, Jennifer Earnshaw, of Kansas City, Kansas. Her daughter — and Dewey’s cousin — Kaitlin Kennedy, 25, died in February 2022.

“My daughter didn’t ask to be murdered,” Earnshaw said. “My nephew didn’t ask to be murdered.”

The night David Hill died in 2018, he bought heroin. But what he got was laced with fentanyl, his brother said.

David, a former college baseball player, had become addicted to painkillers after returning home to Leavenworth. His body had been abandoned in a public restroom near a popular downtown gathering spot in his hometown, moved there from another location.

“My brother made a choice that night, and that was to put a needle in his arm,” said James Hill, who got clean after David’s death. “But the choice my brother didn’t make was to die and to do fentanyl. And I believe that’s the story with a lot of struggling addicts.

“They are making the choice to get high, don’t get me wrong. But they’re not making the choice to die.”

The rise of an epidemic

Hearing that more than 850 people in our area have died from this one drug even shocks the people who encounter fentanyl every day.

“Oh, my God,” Akin said about the total. “Until I heard you say that, it didn’t feel real. … We hear, especially in Clay County, about overdose cases where people lose their lives. But we don’t hear about Jackson County. We don’t hear about Cass County and Miami, Johnson, Wyandotte, Leavenworth and Platte.

“That just seems like so many.”

The Star’s analysis of the medical examiners’ data on fentanyl-related deaths in the nine-county region found that the number of fatalities rose dramatically over the last several years.

Overall, the number of fatalities increased by 584% across all counties from 2019 through 2022. This increase was even more pronounced in Jackson County, where the number of fentanyl-related deaths jumped 654% — from 22 to 166 fatalities — in that same time frame.

The data showed that across the nine counties, those between the ages of 20 and 40 were hit hardest. Of the total deaths, 223 were people in their 20s, 255 victims were in their 30s and 148 deaths involved people in their 40s.

“I have never seen this many cases like this just skyrocket,” said Dr. Lindsey Haldiman, Jackson County medical examiner, adding that her office didn’t even track fentanyl when she first got there in 2015. “We’ve always had meth, we’ve always had cocaine, but I’ve never seen this many from one drug.”

In the Kansas City area, law enforcement began to recognize the severity of fentanyl in early 2020, just as the nation was in the height of the COVID pandemic.

In May of that year, two teens from Johnson County drove to the Northland to buy a pill they were told would “make them feel better,” said Sgt. Jeremy Fahrmeier, of the Clay County Sheriff’s Office Drug Task Force.

“They split the pill up and used it on the way back to Olathe and one girl ended up dying — overdosing and dying,” Fahrmeier said of a case that showed law enforcement across the area that fentanyl had changed the game. “I was just like, ‘Holy cow, I’ve never seen anything before where a kid could take a pill, and they die from it.’

“... Later into 2020, (fentanyl) started blowing up, 2021 was off the chain. And in ‘22, it just keeps getting more and more.”

Back in 2016, the state of Missouri began receiving funding for tracking drug overdoses. What officials saw then and what they see now is vastly different.

“You know when we first started, heroin was the number one biggest cause of death,” said Andrew Hunter, who leads data analysis with the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. “And that’s completely flipped in the last six to seven years.

“Starting in 2020 is when fentanyl kind of became the dominant drug for deaths.”

From 2020 to 2022, Mattivi said, the number of fentanyl submissions to the KBI laboratory increased 900%.

“And the thing that’s even more concerning about that is that the trajectory hasn’t plateaued at all,” he said. “In fact, it hasn’t even tapered.”

‘Selling stuff to kill our people’

In the two recent GOP presidential debates, nearly every candidate mentioned the need for more action to stop the manufacturing and distribution of fentanyl. They called for a crackdown at the Mexican border, where the synthetic opioid is being smuggled into the U.S.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy even raised the issue as he was leaving his top post after being ousted last month.

“Fentanyl is poisoning and killing 300 Americans every single day,” he told reporters. “That is equivalent to a full airplane crash every single day in our country.”

At an Oct. 3 news conference, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland announced actions the government is taking, including the first-ever charges against China-based chemical companies for trafficking fentanyl precursor chemicals directly into the United States.

“Fentanyl is the deadliest drug threat the United States has ever faced,” Garland said, describing it as “a nearly invisible poison.”

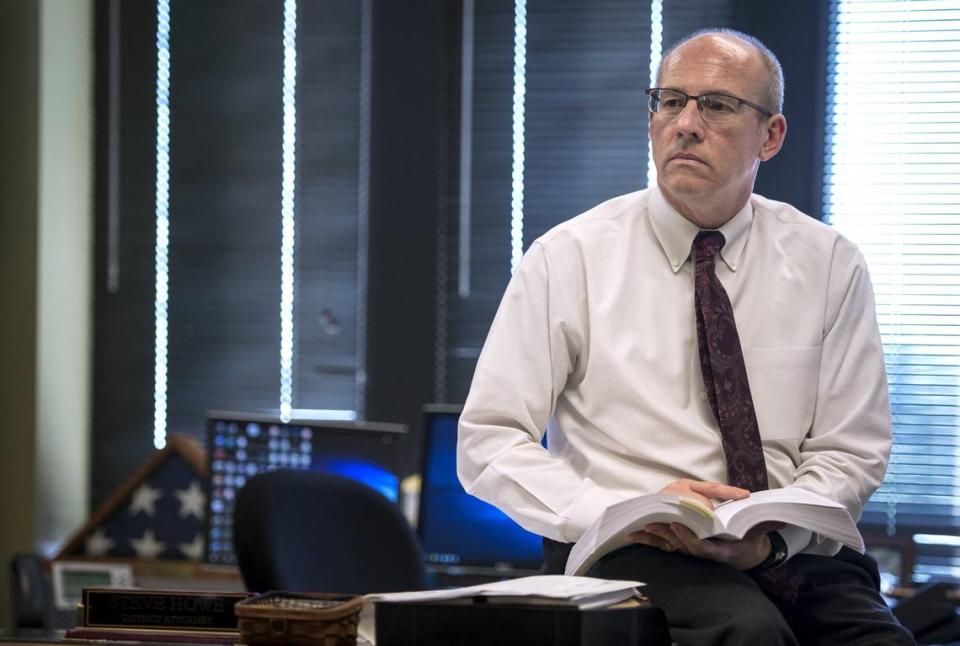

And that’s why federal authorities must do more, said Johnson County District Attorney Steve Howe.

“My personal view is that they ought to deem the cartels as terrorist organizations because they’re intentionally selling stuff to kill our people,” Howe said. “We ought to designate them that, and treat them as such.”

Fentanyl kills more people through overdose than any drug out there, Howe said. In Johnson County, he told Kansas lawmakers in February, the number of overdose deaths associated with fentanyl had tripled in the last three years.

He and others point to the way the illicit drug is being made. Not in highly regulated pharmaceutical labs by trained chemists, but in 5-gallon buckets in garages or warehouses by cartel members who haphazardly mix the materials using tools as primitive as a boat paddle.

There is no exact science or standard involved in the process. And what that means is users have no way of knowing if the pill they bought contains a deadly amount of fentanyl that could instantly kill them.

“It’s like Russian roulette,” Howe said. “This ought to be one of the top three priorities of the federal government.

“I think law enforcement can only do so much. … Literally, it’s like Whack-a-Mole. And I think it’s incumbent upon all our elected officials across this country to make it a priority.”

‘Mommy and Daddy won’t wake up’

Katrina Smith went to her son’s home in Independence on Dec. 19, 2021, to check on him after he hadn’t returned her messages all weekend. She hadn’t spoken to him in three days.

After she pounded on the door for 20 minutes, the 4-year-old daughter of her son’s fiancee answered and quickly said: “Mommy and Daddy won’t wake up.”

There on the kitchen floor, their arms wrapped around each other, were Smith’s son, James Addams Jr., 29, and his fiancee, 31. Their autopsies would later reveal that Addams died of fentanyl and ethanol intoxication and his fiancee died of “fentanyl, alprazolam and oxycodone combined toxicity.”

Their deaths had been recorded on the home security camera, Smith said. The little girl and her 3-year-old sister had been in the home during the nearly two days since the couple had died. The security footage showed that the girls had tried to cover the couple and feed them cookies.

“They did not OD,” Smith said of her son and his fiancee. “This was a homicide, there’s no other way to look at it. … They were poisoned.”

Drug overdoses are typically ruled accidental deaths unless there is proof that someone purposefully administered the drugs to someone without their knowledge with the intent to kill them, said Haldiman, the Jackson County medical examiner.

“And it’s very difficult to prove that,” she said.

A person could still be prosecuted for someone’s death even though the manner of death is ruled an accident, Haldiman said.

“I think a lot of people get upset with us because we’re putting ‘accident’ as the manner of death,” she said. “We’re not saying that somebody is not at fault for this death.

“We’re saying that this person took this medication or this drug, illicit drugs, and died and they weren’t intending to, and there wasn’t another person that forced them to take the drug.”

Independence police stopped investigating the death of Smith’s son, considering it an accidental overdose, she said. But one DEA agent continues to look into it.

Smith said she won’t rest until authorities find and arrest the person who sold the couple the fentanyl pills that they thought were “Molly,” a synthetic party drug also known as ecstasy.

“I want him charged with manslaughter,” she said. “I want to write an impact statement and to read it to him in court. And I hope that he dies in prison. That would be my justice.”

One life-saving solution

On a warm and windy September Saturday in downtown Leavenworth, parents and relatives and friends marched the streets demanding justice for the young people in the surrounding community who died at a time where they were just getting started in life.

Cruz was 15. Shawn was 25. Desi’Ree only 19 and Caleb, 18.

As these loved ones explained to a crowd of roughly 200 people what fentanyl took from them, they also pleaded for families and city officials across the KC area to equip homes and police officers with Narcan, the brand name of naloxone, a medication that counteracts the life-threatening effects of the synthetic opioid.

Many agencies and nonprofits are now providing naloxone free to Kansas and Missouri residents. It also is available over the counter at many pharmacies in both states.

“All the Kansas City, Missouri, (police) officers carry Narcan,” Kelly Garner said from the stage, adding that many other agencies in the region do, too. “Leavenworth … however, does not carry Narcan.”

She has met with Leavenworth Police Chief Pat Kitchens about the issue multiple times, she said, telling him that she believes Narcan would have saved her daughter, Desi’Ree Washington, earlier this year.

“As a mother who has lost her child, I find it really irritating that something so free and so available to us is not available to Leavenworth,” Garner said at the rally.

Indeed, unlike dozens of other police agencies in the KC area, Leavenworth has not equipped its officers with the medication. At least not yet.

“It is absolutely coming,” Kitchens told The Star last month. “Our plan has been in the next couple of weeks, at the end of October or first of November, to get it deployed to all the officers.”

On Wednesday, Kitchens told The Star that his officers should be equipped and trained to use Narcan in the next two weeks.

The chief said Leavenworth didn’t delay getting the medication for officers, but that his agency operates differently from some in the region.

“The police department (in Leavenworth) doesn’t go to all EMS calls,” Kitchens said. “In fact, fire and EMS, they handle all of the EMS calls. … We don’t go to those very often.”

So whether to equip officers with Narcan wasn’t a “question of philosophy,” he said. “It’s a question of value, judgment and resources. … It’s a resource allocation issue.”

After evaluating the situation, Kitchens said his agency decided to move in that direction to require every officer to carry it.

“Simply because there’s a small chance, however small that chance is, that we would be there first on a call and be able to use it,” Kitchens said.

On March 8, after Garner came home from work to find her daughter lying on her bed “not breathing” she called 911. And Leavenworth officers were first to the scene, responding in about four minutes, Garner said.

But they didn’t have Narcan. And it was another few minutes before EMS showed up, Garner said, and they didn’t give it to her daughter immediately.

“Narcan could have saved my daughter’s life,” Garner said. “So when I tell him (Kitchens) that one pill can kill, it’s true. One pill can take your life.

“One mistake cost my daughter her life at just 19 years old. … One pill changed my life forever.”

The Star’s Lisa Gutierrez and Bill Lukitsch contributed to this report.

Illustrations by Neil Nakahodo and page development by Susan Merriam and David Newcomb.

Editor’s note: Deadly Dose is an ongoing investigation into the toll fentanyl has taken on the Kansas City area and responses to it. The project features stories about the broader impact of fentanyl and dozens whose lives were cut short, the challenges of policing the problem, public health efforts to prevent overdoses and community outreach to save lives. Today’s stories are free to read online as a community service.