Women in Egypt thronging to social media to reveal sexual assaults, hold abusers to account

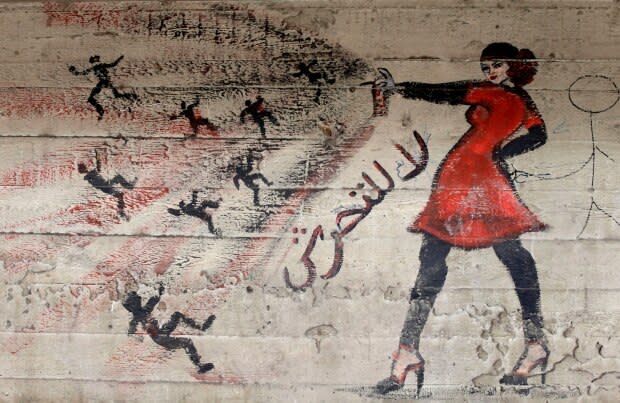

In Cairo, secrets long suppressed have been rising to the surface — and with them hopes the country may be experiencing a feminist movement capable of challenging the culture of impunity that has long accompanied gender-based violence in Egypt.

Online testimonials over the summer by hundreds of women on social media accounts offering anonymity have led authorities to open investigations into two alleged rape cases involving young men from wealthy and influential families.

"Egypt is on fire," said Mozn Hassan, head of the women's rights organization Nazra for Feminist Studies. "On fire for more than three months talking about different incidents in different sections and layers [of society]."

Social media, she said, has offered Egyptian women a safe "public sphere" that lets them know they are not alone.

In July, that space led to the arrest of a former American University in Cairo (AUC) student named Ahmed Bassem Zaki, accused of raping a number of women and blackmailing them for sexual favours. A Cairo court has set Oct. 14 as a trial date for Zaki.

"We at first just wanted him to admit it, that he did these things," said Sabah Khodir, an Egyptian writer and poet who was one of the first to post online warnings about Zaki when she started to hear about his alleged behaviour from friends.

WATCH | How Egyptian society shapes men's perceptions of women:

It set off a tidal wave with another Instagram account called Assault Police, encouraging women to share any information they had on Zaki.

"Then girls kept coming forward from all over parts of the world," Khodir said. "We realized we actually have a shot at finally getting a serial rapist and predator in jail in Egypt that has money and power."

It also led to an outpouring of other accounts of sexual abuse and harassment as women opened up about their experiences, some buried deep in the past.

Khodir left Egypt for the United States last year after she herself was sexually assaulted. She said it wasn't until after Zaki's accusers started speaking out that she felt able to tell her own story of being abused by a trusted friend.

"There was a lot of manipulation involved, a lot of, you know, but look at what you're wearing," she said. "I think these men never look at women as people ... you know, women are like lollipops or women are like diamonds or women are like cars. If it leaves its door open, it wants to be stolen."

She said she never spoke of it to her parents, but her mother guessed after Khodir became more outspoken online.

Definition of rape 'limited' in Egypt

Challenging the status quo in a socially conservative and autocratic patriarchy like Egypt can be both difficult and dangerous.

Predators are able to hide in the weeds of a distorted morality, enabled by a society where victims of sexual harassment and violence have long been blamed and shamed into silence.

"It will be like, oh, he's bad, but you're also wrong," Khodir said. "And goodness, you don't want to be wrong and a woman in the Middle East because you're not forgiven for being wrong. It's like you don't make mistakes. You're born a mistake. And that's really it."

There are some 102 million people living in Egypt, nearly half of them female. The country places 134th out of 153 on the World Economic Forum's 2020 Global Gender Gap Report.

In 2013, a United Nations survey found that 99 per cent of Egyptian women polled said they'd experienced some form of sexual harassment. Women in Egypt today say not much has changed since then.

"It either [happens] in college or school situations," said one young woman interviewed by CBC News in Cairo in August. "It could be even the street, especially the metro. The metro is not a safe environment."

"There are victims everywhere, even at work," said another. "And ladies will not report it ever because they're afraid of all the scandals that happen."

In 2011 in Cairo's Tahrir Square, the epicentre of Egypt's Arab Spring, a large number of women joined the protests demanding the fall of Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak, who at the time had been president since 1981.

They were heady days, with the country balancing on the edge of a potential new dawn. But in the crowds, some women were assaulted, surrounded by groups of men, stripped and abused by penetrating hands.

That doesn't count as rape in Egypt.

"We don't have a definition of sexual violence," said feminist Mozn Hassan, who used her NGO to help victims at the time. "And the definition of rape is limited. So rape with a sharp object, oral rape, anal rape, is not a rape."

Arrests signal 'a paradigm shift'

There are signs, though, that the Egyptian government is feeling the pressure of recent events. In August, the country's parliament passed a bill aimed at ensuring the anonymity of victims and witnesses in sexual assault cases.

Nehad Abul Komsan, a lawyer who heads the Egyptian Center for Women's Rights, points to a second case authorities are investigating after allegations were posted on the Assault Police account about a gang rape at a Cairo hotel in 2014.

"To have a case six years ago and [the] public prosecutor open investigation in this case — this is completely new in the judiciary system at all. That's why I believe it is a paradigm shift."

Police issued arrest warrants for eight young men accused of gang raping a young woman and videotaping the incident at a private party at the Fairmont Nile City, a luxury hotel. Authorities even extradited three of them from Lebanon.

As in the Zaki case, they were wealthy men from influential families.

"I knew two of these guys, so I was, like, very triggered," said Raguia Mostafa, another woman who found herself confronting her own history when Egyptian women started sharing their stories this past summer.

"It kind of just reminded me of my own incidents when I was raped and when I was abused."

WATCH | Changing societal attitudes in Egypt:

Like Khodir, Mostafa has left Egypt, fortunate enough to have the means to do so, she said. A graduate of AUC, she speaks five languages and is currently living in Mexico City.

Her molestation at the age of 11 by an older friend whom she maintained a relationship with for years is just one instance of abuse she speaks about.

When she decided to confront him, there were repercussions, Mostafa said.

"He has all these screenshots that he's using against me. Like 'she can't say I groped her if she did this consensually later.' It's like, no man, I can because I was a kid. I didn't understand. And the fact that it took me 12 years to realize what you did to me is f--king scary. But he won't acknowledge that. Instead he chose to threaten my parents."

It's not just a judgmental society women have to take into account as they navigate these issues, but an authoritarian regime that can give with one hand while taking away with the other.

Authorities, for example, might have arrested the young men accused in the Fairmont case. But they also arrested some of the witnesses, using images from their phones to charge them with immoral behaviour. One woman was apparently subjected to a virginity test.

"It's just insane how much power the government has," Mostafa said. "The fact that the government can just arrest rape victims and witnesses to a rape just like that for no premise. No one can do anything about it."

Regime tough on 'TikTok girls'

A Human Rights Watch report has also accused the Egyptian regime of deliberately targeting and jailing female social media influencers. Charged with "inciting debauchery," some have been given jail sentences of two years just for dancing on TikTok.

The "TikTok girls," as they're widely known, come from poorer social classes than the women involved in the Zaki or Fairmont cases — meaning they have fewer tools at their disposal to defend themselves.

"I think we have to see it within the context of how this regime is trying to control everything," Hassan said, referring to a relatively new cyber-crime law being employed by the government aimed at the abuse of "Egyptian family values."

Hassan herself has been subject to a travel ban since 2016, a form of harassment regularly employed by the Egyptian government.

Nehad Abul Komsan said it's important not to divide women experiencing oppression and abuse into different categories, such as rich and poor.

"Being economically empowered doesn't mean you're not afraid from social stigma or condemning. All the families, they feel there is a problem that would affect their [daughters' futures] and their chances of marriage and all this stuff. There is no difference of being poor or rich on this issue."

It makes it clear just how deep societal change will have to be for real progress to arrive in a country where women still make up only 24.7 per cent of the workforce.

Raguia Mostafa said she will not return to Egypt, unwilling to accept the limits it would place upon her.

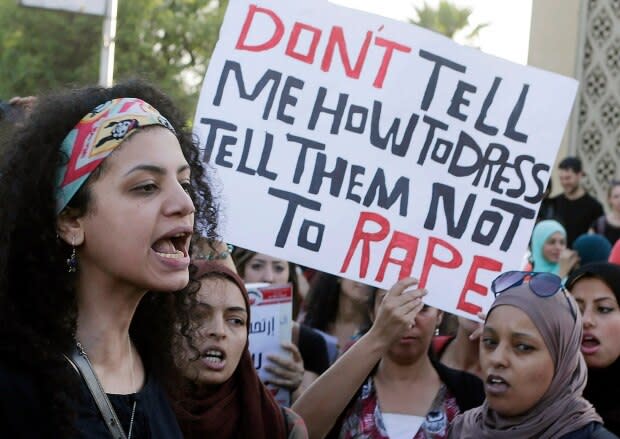

"Instead of protect your daughters and tell your daughters not to go out at night or tell them to dress a certain way, I would much rather for the dialogue to form into like, teach your men, teach your sons to respect women," she said.

Sabah Khodir said she would like to return from the U.S. one day but is unsure if she can. It's one reason why she's uneasy labelling what's happening in Egypt as the country's #MeToo movement, saying the consequences are different in Egypt.

"The consequences aren't that I tell my story, and the worst thing that's going to happen is that somebody is going to say I'm a liar. The consequences [are] that I'm going to tell my story and there's a very good chance I might not see my family again," she said.

"Or there's a very good chance that someone's going to try to hurt me and harm me into being quiet. And there's a very good chance that I'm going to walk out of this with absolutely nothing."