Biden’s Dangerous Two-Step on Climate

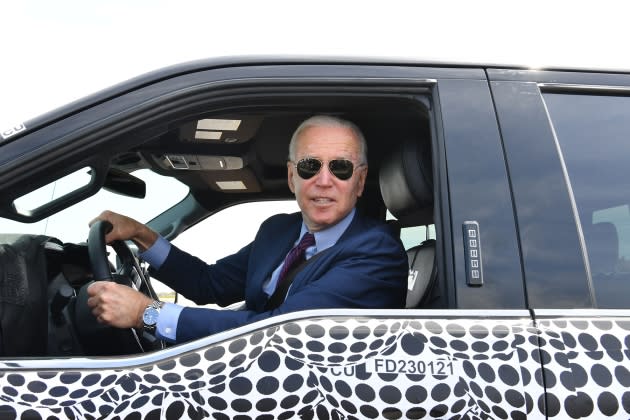

Electric cars are awesome. Now, thanks to new vehicle-emissions standards proposed this week by the Biden administration that aim to accelerate the adoption of electric cars, it’s pretty obvious the internal-combustion engine is the dodo bird of energy technology, soon to exist only in the memories of aging car buffs and mechanics. And that is a very big deal. If you care about the fate of human civilization in our rapidly warming world, this is a good moment to smile and feel hopeful that all is not lost.

But now let’s somber up and ask a tough but necessary question: If the Biden administration is so gung ho about maintaining a habitable planet, why did it approve a big-ass oil-drilling project in Alaska a few weeks earlier? The Willow Project, as it is known, is a $7 billion drilling project that began in the 1990s when crude-oil producer ConocoPhillips acquired leases to develop oil inside the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, a 23 million-acre area on the state’s North Slope that is the largest tract of undisturbed public land in the United States. In 2016, the company drilled two exploratory wells and discovered what it determined was economically recoverable oil. After more than five years of permitting and legal fights, the Biden administration finally approved the proposal, allowing three drilling sites with up to 199 total wells. Over its 30-year life, the Willow Project could produce up to 600 million barrels of oil and release as much as 230 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere — roughly equivalent to emissions from 70 coal plants.

More from Rolling Stone

'How to Blow Up a Pipeline' Is the Hottest Date Movie of the Season

Fungus Meat? Lab-Grown Halibut? Meet the Scientists Growing Your Next Meal

“This is the crux of the climate problem,” says Jamie Henn, a longtime climate activist and the director at Fossil Free Media, a nonprofit media lab working to end the use of fossil fuels. “The Biden administration is taking some bold action — but they only want to tackle the demand for fossil fuels, not the supply. That’s like trying to cut a piece of paper with only one side of the scissors.”

For Biden, and for virtually every other living thing on the planet, this is the moment the rubber hits the road. Biden was elected in 2020 with a pledge to cut CO2 pollution in half by 2030. The Inflation Reduction Act, which passed last year in a hard-fought battle with Congress, will channel $390 billion into clean-energy and climate-related projects over the next decade. That’s a huge step in the right direction. But it’s not enough. Fossil fuels must die. And the quicker the better.

You can think of the push for electric vehicles as part of a slow starvation campaign against Big Oil. “There are about one billion machines that use CO2 on the planet — from power plants to home heating furnaces to lawn mowers,” says Leah Stokes, a professor of environmental politics at University of California, Santa Barbara and the author of Short Circuiting Policy, a book about the battle over clean energy and climate policy. “If you get rid of those machines, you get rid of oil.” Or, to put it another way, if you electrify everything, fossil fuels will die because no one will need them for anything. It’s a very Silicon Valley idea — fossil fuels are land lines, and renewable energy is an iPhone. Innovation and investment will pour into clean energy, making it ever cheaper, ever more ubiquitous. Stokes calls the “electrify everything” movement “a new theory of social change.”

But it is not at all clear that simply attacking the demand for oil will be enough. Even staid governmental bureaucracies like the International Energy Agency have argued that in order to meet the Paris climate goals, expansion of new fossil-fuel development has to stop now. If not, climate chaos will only accelerate. As writer and activist Bill McKibben argues in a recent Rolling Stone story: “The fossil-fuel industry has continued to explore and prospect, and now controls reserves of coal, gas, and oil that, if burned, would produce 3,700 gigatons of CO2. That’s 10 times the amount scientists say would take us past Paris temperature targets.”

In 2020, then-candidate Biden made an explicit promise that there would be “no more drilling on federal lands.” “Period,” he emphasized during a New Hampshire town hall. “Period, period, period.” That period, unfortunately, now looks more like an exclamation point. According to the Center for Biodiversity, federal data show the Biden administration approved 6,430 permits for oil-and-gas drilling on public lands in its first two years, outpacing the Trump administration’s 6,172 drilling-permit approvals in its first two years. And there is plenty of evidence that, in the largest sense, ignoring the supply side of our fossil-fuel addiction is not working. Despite all of the money that has been poured into clean energy in recent decades, the percentage of primary energy from fossil fuels has only declined from 87 percent in 1990 to 81 percent in 2021. CO2 emissions in the U.S. are down about 15 percent since 2005, but only back to the high level they were in 1990. Meanwhile, global CO2 emissions are up by about 40 percent since 1990. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere today is comparable to where it was around 4.3 million years ago during the mid-Pliocene epoch, when the sea level was about 75 feet higher than today, the average temperature was 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than in pre-industrial times, and large forests occupied areas of the Arctic that are now tundra.

Biden inherited the Willow Project from the Trump administration, which had initially approved the project in 2020. But in 2021, a federal judge in Alaska reversed that decision, saying the environmental analysis was flawed and needed to be redone. The footprint of the drilling operation was reduced, and after months of review, the project was approved. Why? “The environmental-review process in a project of this scale is very complex,” says Erik Grafe, an attorney at EarthJustice who has been involved in lawsuits trying to stop the project. “But in the end, it is a political decision.”

For climate activists, Willow was another in a succession of fights against infrastructure that have galvanized the movement: the Keystone XL and Line 3 pipeline campaigns, for example, or the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign that has shut down hundreds of old coal plants. But opposition to the Willow Project reached a new level. An online petition gathered more than 6 million signatures. According to Alex Haraus, an independent creator and impact producer who was involved with the campaign, hashtags related to the Stop Willow movement like #stopwillow and #stopthewillowproject got 650 million views across all social platforms. “Willow was so obviously bad, and in so many ways, that people were really motivated to fight it,” Haraus explains. Stephen Colbert pressed Vice President Kamala Harris about it on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. By one account, even Biden’s grandchildren, who were following the fight on TikTok, were upset about the idea of expanding drilling in Alaska. “I think the White House was really taken aback by the amount of pushback on this project,” says Henn.

But within Alaska, Willow had real support. The entire congressional delegation was behind it, as were large parts of the Alaska Native communities, including the powerful Alaska Native corporations. And the reason is simple: money. Because of the way revenue sharing is set up in Alaska, if and when oil starts rising out of Willow, hundreds of millions of dollars will be begin flowing into communities in the North Slope Borough where the project is located. More broadly, the state also depends on oil money to survive. “Alaska is a banana republic,” one Alaskan activist told me over lunch when I visited the state with President Obama in 2015. “It either has to pump oil or die.” Almost 90 percent of Alaska’s revenues come from oil. In addition, every Alaska resident gets a monthly check from what’s called the Alaska Permanent Fund, which is an investment fund built up from oil revenues. This year, the check is expected to be about $3,900 for every man, woman, and child in the state. For a family of four, that means a $16,000 annual check. If you stop drilling, you’re literally taking money out of people’s pockets. Which is why, given that Alaska’s oil-and-gas production is only about 25 percent of what it was a few decades ago, there’s no more urgent task in Alaska than planning what a post-fossil-fuel future would look like in the state.

Opposition in Alaska has come largely from the Nuiqsut tribe, which includes a community of about 400 who live near the drilling site and will suffer the most, from air pollution to having the migration of caribou, which they depend on for food, disrupted. Jade Begay, director of policy and advocacy at NDN Collective, an indigenous-led activist and advocacy organization based in Rapid City, South Dakota, stated: “Just because Nuiqsut is a small community doesn’t make it any less wrong for them to lose their land and their culture. No community should be sacrificed. The oil industry and the right-wingers say no one lives out on the North Slope, that it’s just ice. But that’s wrong, and it is racist. It is a dangerous line when you say there are communities that can be sacrificed just for the sake of people and corporations getting rich.”

So why did the Biden approve Willow? He said that it was because they were going to lose in court anyway (several lawyers I spoke with who are involved in the fight to stop Willow just flat disagreed with that view). Others cite the fear of gas-price politics in the 2024 election. “Willow’s just the starkest manifestation of a core tension between sincere climate intentions and the outsize impact of gas prices on electoral politics,” one senior administration official tells me. The White House is gambling that it can push hard enough on the demand side to make a big dent in CO2 emissions without provoking a full-frontal assault from Big Oil or a backlash from SUV-loving moderate voters.

Environmental groups still hope to stop Willow in court before the drilling begins next fall. But for many climate activists, the real problem in the administration — committed to climate action as they certainly are — is the fear of going toe-to-toe with Big Oil. “The White House is unwilling to engage in the politics of confrontation,” Henn says. Collin Rees, the U.S. program manager at Oil Change International, says that restricting supply of fossil fuels requires a whole different level of political engagement than, say, pushing for more electric cars. “The oil industry can handle cuts in demand, because they believe they can always find new outlets for their product,” Rees says, citing the expansion of liquified-natural-gas terminals that allow oil-and-gas companies to export their product as a prime example. “But when you are messing with supply, you are messing with their existence.” Reserve-replacement ratio is a key metric on any fossil-fuel company’s balance sheet — without future reserves to show investors, they have no viable future.

But by failing to take on Big Oil directly, Guay, among others, thinks the White House is misreading the room. The climate movement is no longer a daydream of lefty environmentalists — it is loud and powerful and young and growing fast. And if Biden wants people to get out there and knock on doors for him in 2024, they want real action. What would that look like? Here’s a short list: making good on Biden’s vow to stop all fossil-fuel leases on federal land; eliminating fossil-fuel subsides; taxing Big Oil’s windfall profits; and stopping the permitting of new export terminals and expanding infrastructure like the $39 billion, 807-mile long LNG pipeline in Alaska that the U.S. Department of Energy approved this week.

None of this would be easy. The risk of political blowback is high. But then, so are the stakes. The fossil-fuel industry is going to wither and die anyway — the faster it happens, the faster we can get on with inventing a better future for ourselves. “The climate fight is about politics and power,” Guay argues. “If you’re not willing to have the hard fight, you’re not really fighting the fight.”

Best of Rolling Stone