Investigator couldn't determine what exactly happened to $211M raised by failed Saskatoon real estate group

A court-appointed investigator looking into the Epic Alliance group of companies says the public may never fully know what happened to the hundreds of millions raised by the failed Saskatoon real estate venture.

"Based on the unaudited books and records of EA Group, total funds raised from Investors amounted to approximately $211.9 million," wrote Peter Chisholm from Ernst and Young in the 58-page report.

"Due to incomplete books and records prior to 2019, the Inspector has been unable to reach conclusions regarding the use of Investor funds for that period of time."

On Feb. 25, 2022, Court of Queen's Bench Justice Allisen Rothery assigned Ernst and Young to look into the Epic Alliance affairs. Rothery unsealed the private report on Friday.

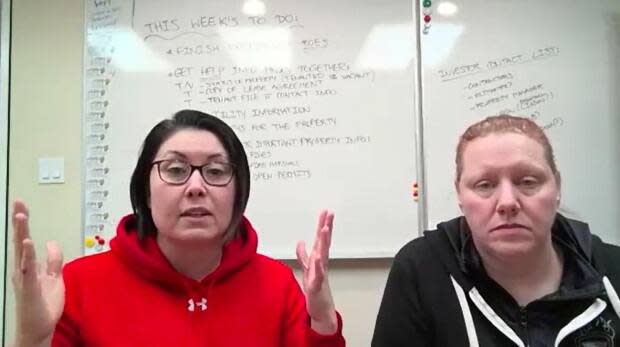

The report establishes that entrepreneurs Rochelle LaFlamme and Alisa Thompson created Epic Alliance in August 2013 and ran it until they told 121 investors in a video meeting on Jan. 19, 2022, that there was no money left.

"At the end of the operations of the EA Group, only nominal cash and other assets remained," Chisholm wrote.

The report details how the pair created an "eco-system" of inter-related companies that bought more that 700 homes, the bulk in Saskatoon's core neighbourhoods.

It raises questions about how the pair enticed investors into their scheme and how the company used fresh money to pay off existing obligations. It also questions how homes were appraised and mortgages were obtained.

Saskatoon lawyer Mike Russell represents the investors and made the application for the investigator.

"One important point here, a very concerning point, is there are no records available to the inspector before 2019," he said in an interview.

"So you've got, from 2013 to 2019, it's a complete black box. We have no idea what happened in that time period."

The analysis of how Epic operated focused on the period of 2019 to early 2022.

An epic history

LaFlamme and Thompson created Epic Alliance in 2013. It soon evolved into a web of named and numbered companies, including Epic Alliance Real Estate, Epic Alliance Electrical, Epic Accounting and Bookkeeping, and Epic Holdings. It had 118 employees.

They created and ran three main ventures: a loan program based on promissory notes, a "Fund-A-Flip" program and a "Hassle Free Landlord Program."

The company built up a pool of capital by enticing people to give Epic between $50,000 and $500,000 in exchange for a promissory note. The single-page notes, of which multiple examples were provided in affidavits, were models of simplicity. They featured the loan amount, when the term began and ended, and the interest rate.

The rate of return varied from 15 to 20 per cent.

"You have a pool of unsecured funds that can be used for whatever. There's no specific purpose given for those funds when they're loaned," Russell said.

The "Fund-A-Flip" program had investors buying homes through Epic, doing improvements and upgrades, and then selling for a profit. The company's promotional material suggested a 10 per cent return on a one-year investment.

Finally, Russell said the "Hassle Free Landlord Program" had investors — most out of province — buying homes acquired by Epic through the Fund-a-Flip program. The investor took out the mortgage on the home and Epic took responsibility for everything from finding tenants to maintaining the property.

It offered the investor a 15 per cent guaranteed rate of return.

The Ernst and Young report revealed that, from 2019 to 2022, much of the new investor cash went to fill in the gaps on earlier obligations. It showed that 82 per cent of the company's revenues came from investors and 18 per cent came from the operations of its businesses.

The promissory note program attracted the attention of the Financial Consumer Affairs Authority of Saskatchewan (FCAA), leading to an October 2021 cease trade order.

The order stated that Epic had given information and advice on how to invest in securities, including real estate investments and promissory notes, without ever having registered as dealers or advisors.

Investigator Peter Chisholm wrote that the company ignored the cease trade order.

"The Inspector reviewed signed promissory note agreements indicating that the EA Group raised a total of $370,000 from four investors during the period from October 21, 2021, to October 29, 2021 (during which time the CTO was in effect)."

Challenging investigation

The report details significant challenges the investigator faced from day one.

Searching the former Epic Alliance head office at 410 Avenue N in Saskatoon turned up 84 banker's boxes of paper records. But it's what wasn't there that proved troubling.

"The network infrastructure for EA Group was located in a room in the basement of 410 Avenue N. The Inspector identified an empty server rack where several servers containing the network data for EA Group should have been stored," the report said.

"A drill was located on the top of the server rack which appeared to have been used to remove the servers."

A later interview with an IT analyst retained by Epic revealed that the company had hired the computer expert to take the three servers and "to wipe [or erase] the contents of the servers, and to locate a purchaser for the servers," the report said.

The primary server still had data at that point — an estimated 260,000 documents — but "the server documents were highly disorganized and lacked folder structures to facilitate organization of documents and files."

"The server documents also appear to be incomplete."

The road ahead

Russell said the investors must now decide what, if anything, they can do get back some of their money.

"This report would either provide investors with an idea what assets would be available for them to go after, or it would say there are no assets but at least give them an overview of what happened with these companies," he said.

"I think it does an extraordinary job of the latter."