‘Anti-blackness at its core:’ KY lawmakers work to erase years of racial progress. | Opinion

On Monday, Jan. 15, we will celebrate the federal holiday of Martin Luther King, Jr.

It will be 95 years to the day after he was born and 60 years since the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 that he championed removed legal barriers to voting, housing and public accommodations for Black people in this country.

But here in Kentucky, our elected officials are introducing bills that attack racial progress. In particular, Senate Bill 6 and Senate Bill 93 would attempt to nullify diversity efforts in K-12 and higher ed, banning the training in or teaching of “divisive concepts,” such as the fact that just 60 years ago, Black people were prohibited from taking part in crucial aspects of American life.

Efforts in Kentucky and other states to end diversity, equity and inclusion efforts follow similar attempts to ban critical race theory, which also points out aspects of our less-savory history. It’s the pattern of pushback that white conservatives have followed since King’s work began.

“It’s like Groundhog Day,” said Gerald Smith, a pastor and University of Kentucky history professor who edited a volume of King’s papers and most recently published “Slavery and Freedom in the Bluegrass State: Revisiting My Old Kentucky Home.”

“We just play that record again.”

We can go back even further.

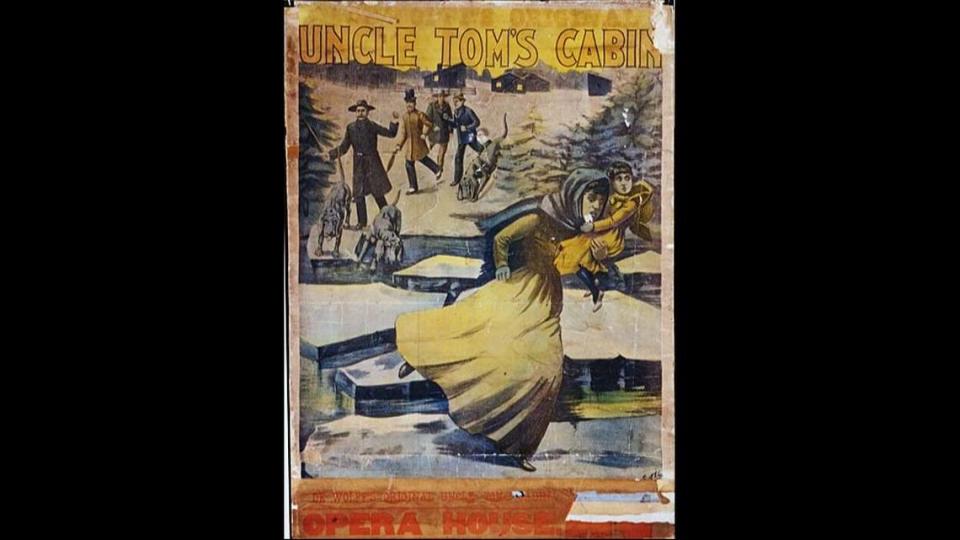

In 1906, the Kentucky General Assembly enacted a law that prohibited anyone “to present, or to participate in the presentation of, or to permit to be presented” in any “opera house, theater, hall, or other building under his control” any play “that is based upon antagonism alleged formerly to exist between master and slave, or that excites race prejudice.”

It was aimed at traveling shows of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel by Harriett Beecher Stowe, which showed slavery — and Kentucky — in a less than good light.

It was just two years after Kentucky lawmakers passed the Day Law, which re-segregated Berea College from being the first school to educate Black and white students together.

“In the Journal of the Civil War Era,” in 2011, historian Anne Marshall wrote the law was pushed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy because both the novel and play presented “a picture of slavery in the South that is essentially false.” While slavery was sometimes cruel, the organization said, most relations between slave and master were “kindly and mutually beneficial.” (There was no outcry over showing “Birth of a Nation,” Smith points out.)

History repeats itself over and over and over again, Smith said. King would be horrified by the Kentucky General Assembly. But he would not surprised.

“It’s appalling to think that would be legislation to strike down these DEI programs because they work toward freedom, justice and equality — how can we strive a more perfect union if we don’t address greater levels of equality?” Smith asked.

“I have to think about the people who endorse this kind of legislation. Where is this coming from, what is their perception and their perspective, what have they observed and experienced to cause them to support this kind of legislation? Do they truly believe what they are proposing is in best interest of the nation? It’s not only unjust, but quite frankly, it’s immoral. King would definitely speak to that.”

‘Anti-Blackness at its core’

Most of the legislation’s supporters are white men from Kentucky’s rural areas who believe that striving for more inclusion and diversity in education and the workforce has somehow bilked them out of jobs and opportunities.

That is an argument, of course, until you look at the top layer of every institution in this state and country, from corporations to schools to our own General Assembly, all of them dominated by white men.

“There has never been a time in history when the perception of Black advancement has not triggered white blowback,” said Chester Grundy, who has worked on Lexington’s MLK Day event for the past 50 years, and been co-chairman for for the past 30.

“That’s fact, from Reconstruction onward —if you move ahead, then I lose.”

UK history professor Anastasia Curwood is the author of a biography about Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress. She said Chisholm liked to quote Frederick Douglass, who said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

“The gains of the movement are much more fragile than most people understand them to be,” Curwood said. “Many people would like to think that racism is solved, but we still have a lot of inequality that needs to be remedied. DEI initiatives have been a tool to attempt that remedy.”

Chisholm was first elected in 1968, the same year King was assassinated. Today there are 29 Black women in Congress.

Kentucky has 42 women in the General Assembly; three are Black and one is Asian American. There are five Black men, two in the Senate and three in the House.

Whatever we have done as a society for diversity and inclusion has not moved the needle that much.

On Wednesday, University of Louisville professor and Courier-Journal columnist Ricky Jones penned a column asking if in light of the legislature’s recent moves, it’s time for Black people to leave Kentucky.

“This is not about BLM, DEI, CRT, it’s not about any of this stuff,” he said in a phone interview. “It’s about anti-Blackness at its core. It’s white supremacy being exercised through political office and legislation. These legislators know exactly what they’re doing.”

Jones pointed out that Kentucky is now the eighth-whitest state in the country, without any real Black social, political or economic power, much less potent resistance to what happens in Frankfort. But these kinds of laws will force Black people to leave and people who value diversity to never come in the first place.

“That’s a consequence and these people don’t care,” he said. “They’re committed to having and maintaining a white ethnostate. The fact it will be a dumb white ethnostate seems to be inconsequential.”

‘In the end, hope’

Here’s the good news: While it’s depressing that our lawmakers want to spend time and energy on culture war issues, in many ways, it’s too late.

How can you possibly suppress “divisive concepts,” when they make up so much of our history? How do you keep from information flowing like water? They couldn’t do it in 1906 with “Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and they certainly can’t do it in an age of social media.

“Students are smart enough to realize now that you can’t keep race out of classroom or off campus,” said UK’s Smith. “It’s in the news — whether it’s athletics or politics or education — it’s all there and inquiring minds want to know.”

MLK Day is a good time to reflect on why people still resist his message about so many things. People need to read beyond “I Have a Dream” to other, later works to understand how well King understood America’s racial struggles.

“It’s aspirational,” Grundy said.

“I think there’s value in people coming together. MLK in my mind represents a benchmark or standard, a vision of a truly democratic ideal. King is one of the most genuine examples of someone who truly believed in the possibilities of a more perfect union, and one that was far grander than most people understand.

“He was a prophet in seeing America and knowing how he had to respond,” Smith said. “But in the end, he had hope.”

If you go: The annual Martin Luther King Day march will start at 1 p.m. at Central Bank Center followed by the program featuring Rev. Kevin W. Cosby, president of Simmons College at 2 p.m. The program will also feature musical performances by United Voices Chicago and United Voices Lexington. Information: https://oid.uky.edu/news/annual-mlk-day-celebration-lexington-set-jan-15-2024.