Anti-regime activists in Canada accuse Cuba of using YouTube channel to intimidate them

Thirteen Montrealers say they've been targeted by a campaign of harassment launched by the Cuban government to keep them from protesting against one-party rule on the island.

A social media account which — according to a Cuban defector — is being run by Cuba's state security has been spreading detailed allegations against the 13 men accusing them of trafficking cocaine from Colombia to Canada.

Carlos Andrades said he's one of them. On March 21, he arrived in his native Havana for a visit with his 95-year-old mother. Travelling with him were his Canadian-born daughters and grandson.

Andrades said he has long been active in opposition circles and has been prevented from entering Cuba on previous occasions. He said he travelled on this occasion with some trepidation.

"I have a 95-year-old mother, so I have to go," he said.

Soon after arriving, Andrades said, he was visited at his hotel by a woman in military uniform who gave him a piece of paper ordering him to present himself for an interview at a detention centre operated by the Cuban Ministry of the Interior.

His interrogation — by a man who introduced himself as Col. Luis Morales — was videotaped and would shortly be used as one of the elements in an elaborate allegation against him and a dozen fellow Cuban-Canadian dissidents.

Andrades said the interrogators showed him evidence that he had participated in demonstrations and posted comments critical of Communist Party rule. Under new Cuban laws, online criticism can be prosecuted as cyber-terrorism.

"They show you the picture and you have done this, and you have done this. So you are against the wall because you are not in Canada," he said. "Canada cannot protect you in any way."

Andrades said the interrogators also suggested that he was engaged in drug trafficking in order to finance the operations of anti-government YouTubers. They named one in particular: a Montreal-based anti-regime YouTube channel with nearly 90,000 followers.

The arrival of the internet in Cuba has focused the Cuban government's attention on the threat posed by online influencers in exile. It appears to have chosen to strike back using an online weapon — YouTube.

Saying goodbye forever

El Guerrero cubano (the "Cuban warrior") is a YouTube account that broadcasts attacks on enemies of the Cuban Communist Party, sometimes by making use of video of interrogations by Cuban state security.

The person behind the Guerrero account does not show their face in the videos. A recent Cuban government defector has identified the individual behind the account as Col. Pedro Orlando Martínez, head of the political wing of Cuba's National Revolutionary Police.

Andrades said that after his interview, he was allowed to leave Cuba with his daughters, much to his relief. But the interview convinced him that he could not risk returning.

"I knew from the very beginning — I get inside the airplane, that was my last last trip to Cuba," he said. "And I had to say 'bye to my mother. It was not easy."

Three weeks after Andrades returned to Canada, the Guerrero cubano account uploaded its first video revealing details of what it claimed is "a network of drug traffickers that feeds the counter-revolution in Canada."

The videos posted include several clips of Andrades's interrogation. In none of them does he say anything incriminating about drugs, either about himself or anyone else.

In the narration accompanying the first video, the Guerrero claims he has more damning footage from the interview that he will release at a later date. A second video, released two weeks after the first, showed more interrogation clips but still did not include any confessions by Andrades regarding involvement with drug trafficking or allegations against anyone else.

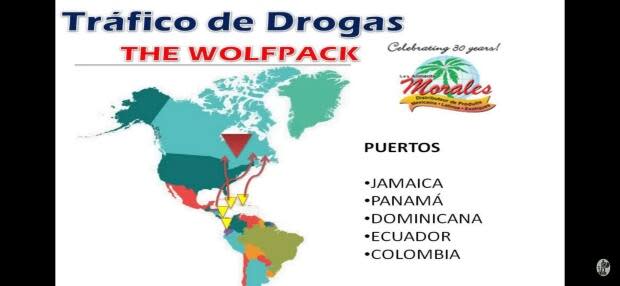

In the videos, the Guerrero cubano accuses 13 Montrealers by name of using a food import business belonging to one of the men to smuggle cocaine bought from a Colombian family network called the Solazars. The account claims the men used another man's trucking company to distribute the drug throughout central Canada, New York and New Jersey.

The money, the videos claim, is to be used for terrorist attacks against Cuba.

"They are poisoning and destroying the Canadian population, especially the youth," says the narration for one El Guerrero video. Over photo images of the Cuban-Canadians meeting with Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre, the narration accuses them of "openly defying the current government of Canada, especially its prime minister, Justin Trudeau.

"They need the Conservatives to come to power in Canada."

Andrades said his Cuban interrogator questioned him about his group's meetings with Conservatives, described Polievre as "another Trump" and told him that Havana preferred to see Trudeau remain in power.

CBC News asked the Cuban embassy about the case but did not receive a response. Public Safety Canada and Global Affairs Canada also did not respond to inquiries about the matter.

'War needs money'

One of the 13 men named in the Guerrero videos was, at one time, a major drug trafficker. Maximo Morales was arrested in 1990 after Montreal police made the city's largest ever seizure of cocaine. Morales was accused of bringing in 1,500 kilograms of cocaine in a year, purchased from the Medellin cartel. He received a ten-year sentence.

The money he made trafficking, Morales said, was intended to finance the operations of the anti-Castro opposition, particularly the purchase of land, arms and equipment for training camps in the Florida Everglades.

The 1980s were a time of ferment in Cuban exile communities, with many groups scheming to depose the Castro regime.

"It was a war," said Morales. "It was an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. And war needs money.

"I was arrested, I received a ten-year sentence. I did my time and after that I reintegrated into the community."

Though he acknowledged that he's "no angel," Morales said he's obtained a pardon and has never had problems with the law since those days. He owns a number of businesses, including a real estate company and Aliments Morales, based in Montreal's east end, which imports and distributes Latin food products.

That business features heavily in the Guerrero videos, which show manifests of cargo shipments that Aliments Morales has imported into the country — such as a container holding ten tonnes of pigeon peas from Ecuador — and allege that those shipments contained cocaine.

Morales said he has had no contact with the world of drug trafficking since he came out of prison and that none of the other 12 men named had any involvement in his illegal business. CBC News has spoken to seven of the 13 individuals named in the video; they all say they have no criminal records.

The 12 individuals include Morales' brother Gerardo — who was still living in Cuba at the time of Maximo's arrest — and his son, also called Maximo, who was a young child when his father went to prison.

Some of the men on the list own businesses that were also identified in the videos. They include a trucking company the videos claim is involved in distributing the drugs, and a dance studio that is named as a meeting place for the supposed conspiracy. Also named as a member of the conspiracy is the Montreal-based anti-regime YouTuber with nearly 90,000 followers.

All of the men named in the videos deny the existence of any such network.

Tito Cardenas is the owner of Titisalsabor dance studio. He said he believes he was put on the list because he made anti-government comments in a Radio-Canada article that was shared widely.

"I think that's when they started to follow me," he told CBC News.

"I think people should be aware that this is a method that all dictatorships use. When you're an opponent of a dictatorship, the first thing they're going to do is attack your reputation any way they can."

Allegations of involvement in drugs and homosexuality are favourites of Cuban state security, he said.

"I think the next step could be to try to put some physical evidence to try to incriminate me," he added. "I have a dance studio where it's relatively easy to plant something. I'm not about to put a guard at the door to bother all my students."

Police can't help

Felix Blanco, a financial adviser also named in the video, said he also worries about being caught in a frame.

"I went to the police and I said, look, I'm afraid that they'll put something in my house, that they'll put something in my car," he said.

Blanco said he called the Canadian Security Intelligence Service [CSIS] hotline and was advised to call the RCMP. He said the RCMP in turn told him to speak to his local police service in Brossard on Montreal's South Shore.

He said that all of the authorities he spoke to said they were unable to help because the campaign is anonymous and comes from outside the country.

He said he was somewhat reassured by the fact that his calls to the authorities were recorded and that Brossard police gave him a card with a case file number.

Unlike most of those on the list, Maximo Morales Jr. (son of Maximo Morales) was born in Canada and has never lived in Cuba.

He said he believes that one of the goals of the campaign is to sow doubt and suspicion within the Cuban exile community and make opposition activists believe that their peers could be regime informants.

"They want to destabilize the community, and they're trying to make the community just gossip — 'this guy is this, this guy is that' — instead of focusing on real issues like, why is there no food in Cuba?" he said.

He said what his community is experiencing is similar to what has happened to some other diaspora groups in Canada.

"I wish the government would do more to protect Canadian citizens and residents who escaped dictatorships like the ones in Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, China, North Korea, Iran," he said.

"Those kinds of regimes don't stay within their own borders. They go outside of their borders to go after the people that talk about them."