Birds flying high, do you know how they feel? New app reveals migration routes, dangers.

Utqiagvik, Alaska is the northernmost town in the United States. Located within the Arctic circle, no roads lead out, only planes. The local Ace Hardware calls itself “The Top of the World.”

Ten-thousand miles to the south in Tierra Del Fuego – the “Land of Fire” – lies Ushuaia, Argentina, the southernmost city in the world. High temperatures rarely reach above 55 degrees in the summer, just warm enough to draw tourists setting sail for Antarctica.

But the cities share something in common besides ice and cold: the whimbrel.

A wading bird with a long, curved bill and legs to match, the whimbrel is wide-ranging. It breeds near the poles in summer, then retreats to the East and West coasts during winter, often traveling thousands of miles in between. That means it spends a lot of time on the wing, said Jill Deppe, senior director of the nonprofit Audubon Society's Migratory Bird Initiative.

“It goes up, it breeds, and it comes right back down ... it hugs the coasts,” Deppe said.

But the whimbrel is in trouble, along with more than 350 other North American bird species that migrate internationally each year. Their long journeys, already arduous, have been made more difficult than ever. Waylaid by human interferences such as light pollution, building collisions, habitat loss and sea-level rise, populations are plummeting.

Disappearing from the skies

Across North America, the total number of birds has decreased 25% in just 50 years, Deppe said. That means for every three birds singing on a tree branch, there used to be one more. The total casualty count: three billion birds.

Most of that loss is driven by migratory bird species, meaning their numbers have fallen even more sharply than those that stay year-round.

“We're very concerned,” Deppe said. “Numbers are in steep decline.”

More: There are 3 billion fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970

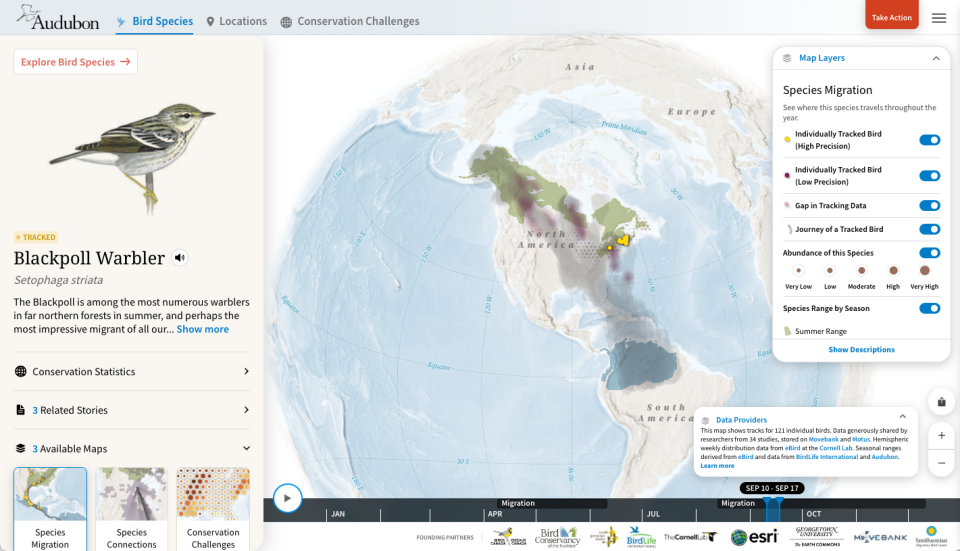

Enter Bird Migration Explorer, a new mapping tool launched Thursday by Audubon and a bevy of collaborators. The free application is designed to inform the public about the behaviors of migratory birds and the dangers they face.

Plug in the blackpoll warbler, and purple and yellow tracking dots spring into action, showing how the bird travels thousands of miles, from the Northeast and Canada in the summer, across the Caribbean and into South America in the winter. Weighing less than half-an-ounce, the tiny bird is the smallest to fly clear across the ocean, sometimes 72-hours straight.

But along its journey the blackpoll also encounters cities, including metropolises like New York, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., where they risk collisions with all-glass skyscrapers. Once they reach their wintering grounds, habitat loss poses another threat. Blackpoll populations are down 95% from the 1970s, Deppe said.

Plug in a city, and users can see what birds are arriving and when, as well as where they're headed. Suddenly the life of the multi-colored Painted Bunting is revealed, as it moves from Texan cities in the summer to those in the Caribbean and Central America in the winter.

“Birds connect us to places far and wide across the hemisphere,” said Chad Wilsey, vice president and chief scientist at Audubon. “The challenges birds face are not just local. They're shared challenges.”

Collaborating for the common good

It's this sense of connection that Deppe and Wilsey hope will spur the public into action.

First, they had to collaborate within their own community.

Wilsey says the Bird Migration Explorer is an unprecedented effort to bring together information and expertise from a wide array of sources. It collected data from more than 500 studies and partners such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, United States Geological Survey, Smithsonian, Birds Canada, Georgetown University and hundreds of independent scientists. It also includes the contributions of citizen scientists who capture bird sightings via Cornell's eBird app.

The data was then plugged into a platform built by Esri, a software mapping company, to visualize the migrations.

"In 50 years we’ve lost nearly one-third of all breeding birds in the U.S. and Canada. But tools like the Bird Migration Explorer provide us with hope,” said Chris Wood, managing director of the Cornell Lab’s Center for Avian Population Studies. “They show not only the commitment of organizations and scientists to reversing these declines, but the dedication of hundreds of thousands of people from across the Americas who provide us with a new way to see our world by contributing data.”

Deppe notes the explorer also offers users information about how to get involved in conserving bird species. That often involves taking local action, but the application can also help the public understand the ramifications of national policies. For example, Deppe said, a person living along the U.S. east coast will discover that local birds migrate to the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, where extractive industries can pose a threat.

“These maps give us a sense of connection to these places," Deppe said. "They give us a sense of stewardship and responsibility for taking care of our local birds where we live, but also protecting those far away places."

Kyle Bagenstose covers climate change, chemicals, water and other environmental topics for USA TODAY. He can be reached at kbagenstose@gannett.com or on Twitter @kylebagenstose.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Birds flying high, do you know how they feel? Migration dangers mapped.