Bohdan Medwidsky, champion of Ukrainian culture in Edmonton, dies of COVID-19

Bohdan Medwidsky, a professor who pioneered the study of Ukrainian culture at the University of Alberta, died on March 28 in the COVID-19 ward at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital. He was 84.

Medwidsky is best known for founding the Peter and Doris Kule Centre for Ukrainian and Canadian Folklore at the U of A.

"He believed that Ukrainian culture is rich and interesting and should be learned by many," Maryna Chernyavska said Monday in an interview with CBC Edmonton's Radio Active.

Chernyavska, the Kule Folklore Centre's archivist, shared an office with Medwidsky for a decade and considered him a close friend.

Medwidksy was born in 1936 in what is now Western Ukraine. When he was two years old, he became ill and his parents sent him to Switzerland for treatment. Then the Second World War began, keeping him separated from his family for a decade.

Like many educated families with clerical ties, Medwidsky's parents and brother fled the advancing Soviets. At 12, Medwidsky was reunited with his family in Austria in a displaced persons camp.

Since he had grown up speaking French and German in Switzerland, he had to relearn Ukrainian.

There in the camp, where Ukrainian traditions were being proudly displayed, he became fascinated with the language and culture. It was a passion that gripped him for the rest of his life.

The family immigrated to Canada in the late 1940s and settled in Toronto, where Medwidsky's parents ran a pharmacy.

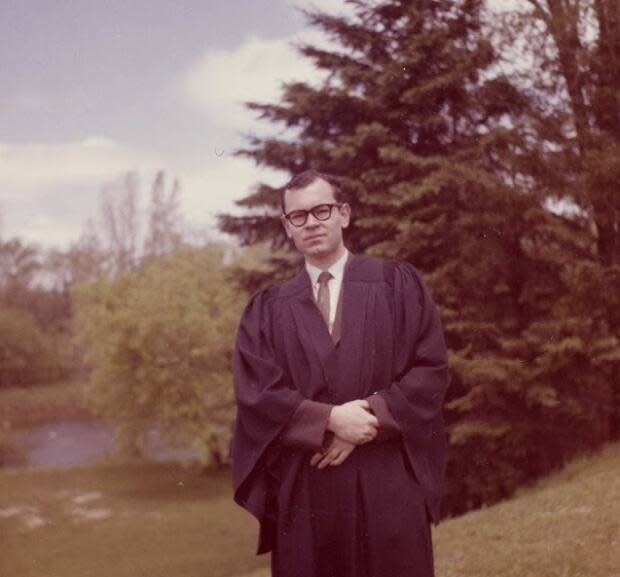

After earning degrees from the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto and teaching in Ontario, Medwidsky moved to Edmonton and became a professor at the U of A. In 1977, he started teaching a course on Ukrainian folklore. That course became two courses, and finally, a full program.

His fundraising efforts and skill at convincing others to support his mission brought the program international acclaim, dozens of graduate students and wide-ranging research on Ukrainian culture.

Andriy Nahachewsky, a retired professor who now lives in Belgium, entered the folklore centre's graduate program in 1982. He went on to earn a PhD and teach in the program, working closely with Medwidsky throughout his time as a student and professor.

"He was definitely not an ivory tower kind of professor," Nahachewsky said, describing his former supervisor and colleague as a driven community member with a dry — sometimes confounding — sense of humour.

Medwidksy's wife, Ivanka Hlibowych, died at a young age, in 1975. Though the widower had family in Ontario, folklore students were his family in Edmonton, his colleagues said. He was a mentor to many and often kept in touch with students long after they graduated.

Though he retired in 2002, Medwidsky remained active at the university for years, showing up at the Kule Folklore Centre every day, even on weekends.

He also sat on the boards of many community organizations, helped develop Ukrainian bilingual schools in Alberta and donated his time and money to countless causes.

Chernyavska said Medwidsky had received his first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine before he was admitted to hospital. He had been thrilled to receive it, but the vaccine had not come soon enough to protect him from the virus.

"I'm sad that we couldn't be with him when he was dying and I'm sad that we couldn't hold his hand," she said.

Above her desk, she keeps a sign with one of the Ukrainian proverbs he was fond of reciting.

In English, it means "what is this, compared to eternity?"

"Although his life wasn't easy and he had to overcome a lot of obstacles, he was able to see this big picture and believe there's something good coming," she said.