Burnout Drained the Color From Del Water Gap’s World. His New Album Brought it Back

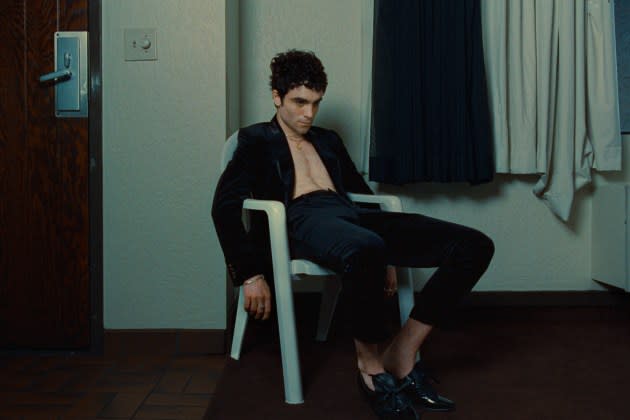

Del Water Gap feels a quiet sense of comfort sitting at the Flower Shop. The restaurant on New York’s Lower East Side hasn’t opened yet, but the room rattles with movement as half a dozen people move inventory and polish glasses. In a few hours, the musician born S. Holden Jaffe will perform for 200 fans from a tiny stage in a corner of the basement lounge here. It couldn’t fit all 7,000 people who requested access to the free event, but he almost prefers it this way. There’s a familiarity to the scale that reminds him of what remains the same, especially when he finds himself sucked into a whirlpool of change that never allows him to settle into one place for long.

Jaffe cut his teeth at venues like this as an NYU student in the early 2010s. At the time, he had many peers around him doing the same thing throughout the city. Some of them stuck around — like Maggie Rogers, who performed in Del Water Gap for a few months before she split off to pursue her own career and Jaffe’s band turned into a solo project. But over the years, that circle began to dwindle. “I saw these bands that I had come up with in New York City quitting these to do other things — to go to real estate, to become accountants, to go to law school,” Jaffe, who grew up in Connecticut, says at the bar. “As the people that I had anchored myself in and my community started to drop off, it was another point of deep melancholy and seeing the world change around me.”

More from Rolling Stone

Del Water Gap and Arlo Parks Search for Balance on New Single 'Quilt of Steam'

Tomorrow x Together Bring Cheer, Pusha T Delivers Dope Set on Lollapalooza 2023 Day 3

Marcus Mumford, Maggie Rogers Hit the Range and Cover Taylor Swift's 'Cowboy Like Me'

There were moments when Jaffe considered tapping out, too. He could manage the highest highs, performing to sold-out audiences at headlining shows and on tours supporting artists like Rogers and Arlo Parks. And he figured out how to stay afloat during his lowest lows, recovering from intense physical and creative burnout while maintaining his sobriety over the past two years. But the time in between those extremes could make his skin crawl with discomfort and uncertainty. “I have felt in the last few years that I’m a bit of a recovering cynic for a lot of reasons — Covid and my upbringing and certain life events that had happened,” he says. “Del Water Gap has been a nice practice in trying to indulge in romance.”

Hoping to bring some color back to his world, the musician distilled those emotional details into existentialist pop on I Miss You Already + I Haven’t Left Yet, his second full-length, out Sept. 29. Walking Rolling Stone through the album, Jaffe unpacked the difficult conversations he had with himself and his collaborators in the recording process; the way living out of suitcases has changed his concept of home; and how he’s learned to give himself and those around him space to grow and heal.

Was there a particular age where you were the most anxious or hyper-aware about time passing?

The reality is that I have felt a version of it at every age. I remember turning 10 years old and being absolutely, existentially devastated. The idea that I would never be single digits again, it made me really sad. I remember crying really hard about it and my parents trying to understand where it was coming from. Coming into teenagehood out of childhood, you certainly feel things change. I grew up in a really small town and there was not a whole lot for any of us to do, so a lot of the kids around me got into drugs really early and drinking, which is pretty common, unfortunately. When that started happening, that was another moment of deep sadness about realizing your childhood is over. I [remember] being really excited to experiment with some of those things, in retrospect, but really feeling that I was not my parents’ son in the same way.

A lot of this album is about talking, referencing old conversations. How do you compartmentalize these interactions as you’re having them in order to be able to write about how they impacted you later on?

I am a pretty shy person and naturally introverted, and I grew up in a very quiet household. My parents are these very introverted intellectuals. They live in the woods, basically. And they spend most of their time reading and talking to each other and going on little walks. They’ve been doing that pretty much since the Eighties. I learned to communicate through inference much more than speaking, as a result of how I grew up. And I think that some of that has a bit to do with masculinity as well. As a man, I think I was raised with a slight pressure to let things just roll off my back, which maybe is less gendered than I’m referring to right now. But it’s something that I have been thinking about in my reflection on some of this over the last couple of years. It’s been a real practice in examining that and understanding, like, if someone says something that hurts, and you don’t say anything and you hold it, it’s gonna come back, somehow. It’s gonna be heavy on you a little bit. I’ve been trying to — rather than seeing avoiding conflict as an act of love — understand that communication is actually a greater act of love.

How does that factor into your collaborative relationships, especially having self-produced most of your previous releases?

Sammy [Witte] was the first person that I ever worked with where I sat down with a blank page and I started an album in a room with someone. The first week of that process was basically me having a panic attack in his studio and saying, “I don’t know what to write about, I don’t know how to do this, I don’t know how to work with other people, I don’t know what to do.” There was a moment when I realized being a great collaborator — and I think the same is true of being a good friend, or being a good partner — can be about the empty space that you leave, stepping out of the way for someone to let them come down and arrive in their own time. About halfway through the process of making the record, I was feeling pretty distressed about not being the person sitting at the computer. And he put the whole album on a hard drive and handed it to me and said, “Do your thing. Go home for two weeks and work on it.” I worked on it for about 48 hours and came crawling back. I said, “I don’t want to be alone.”

You talk about burnout on “Quilt of Steam” with Arlo Parks. Having been on tour with her, have you noticed a particular element of being a musician that causes that feeling to manifest itself?

I was at the first show in the Arlo tour and my tour manager came in and said, “Hey, do you want to eat before the show or after the show?” And I just started spontaneously weeping. I was like, “I just want food to come whenever food normally comes.” A couple of shows in, I went into Arlo’s greenroom and she was like, “Thanks so much for being here. I’m so happy you could do this.” It’s like, yeah, of course. I was really trying to put on a brave face. I didn’t want her to know that I was so tired because the last thing I’d want would be for her to feel like I was ungrateful.

And the tour ended up canceling a few days later. She called me after the fact and was like, “I’m so sorry. I was so tired.” And I was like, “Dude, I was so tired.” We had realized we were both lying to each other and trying to put on a brave face like “Oh, we’re so excited to be on tour.” But that experience really started a greater conversation with me about trying to check in with musicians about burnout. I think especially financially, touring is a much different situation after Covid. Everything’s more expensive. That added stress can add to burnout on top of just being tired.

It can take months to actually recover from burnout, and it feels like by the time you get through it, you’re burning yourself out all over again. It’s a vicious cycle. How do you navigate it?

I came out of college, and I was really grinding and loving the romance of working myself too hard. I was renting a studio that I had between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. I would stay there all night, then go to a job in the morning, sleep for a few hours, then go back. That worked for a few years. And then I experienced the thing that a lot of us experienced in every field, which is that the pandemic became a time for us to actually sit for a moment and reflect — and at the same time, for me, to consider some problems that I was having with addiction and drinking. I came out of the pandemic, started touring, and quickly became a part of a community of musicians that were starting to talk about some of this for the first time.

Your first tour back after this was with Maggie Rogers. What was it like re-entering that space alongside someone you have such a close personal and collaborative relationship with?

One of the greatest joys of getting to know any artist for a long time is the ways in which a mutual admiration for each other’s work can turn into a real friendship. That’s something I have probably experienced most in my creative life with Maggie. We played in Del Water Gap together for a while and I had the honor of working on her last album quite a bit. Maggie’s music is uniquely full of joy and celebration. And I think she’s able to communicate joy in a very left-of-center way. She is also one of my artist friends who knows how to rest. There’s been a couple times since I’ve known her that she’s taken six or seven months off from music. Being on a tour where someone prioritizes that is incredibly rare in my experience. She has a real culture of just enjoying life on tour. Like, we’re going to be traveling the whole country. Why would we not also enjoy the places that we are?

How does your concept of home change when you spend so much time not being settled in any one place?

It’s incredibly fraught. That specific question of home is probably the main bigger-picture concern in my life right now. I have an apartment in L.A. It’s basically a storage locker. I’ve lived there for almost two years and I still have not unpacked. I’m there for four days, every six weeks or so. My family is here in New York, and between New York and L.A. I have essentially lived out of a suitcase for that whole time. It’s been fun to bounce around. I think moving all the time allows you to indulge in some avoidance — but I don’t really know where my home is. My parents grew up in the country and that house is not not home, but I go back there and I feel like a 14-year-old. I go back there and I see my childhood bedroom and there’s soccer trophies and toy soldiers. So that’s not necessarily home. L.A. is where I go to rest and New York is where I go to feel like an artist. The number one goal is figuring out where [home] is.

How do you reconcile your own growth and healing when you return to people who haven’t reached that point yet?

So much of adulthood is meeting people where they are without making yourself smaller. I have definitely experienced being viewed as one of the people that escaped, or that got away from the town. And it’s something I view as happening by degrees. I look back on my teenage years, and if I had made a couple of different decisions, I might still be living there. And that wouldn’t necessarily be a worse life, but it’s a very different life. I think one of the other side effects of traveling so much, and being a bit spread thin, is the very necessary pruning of one’s circles socially, right? You really do have to start making active decisions about who brings joy to your life. It’s a very dynamic process of meeting people where they are. It’s a lot of work and figuring out whether that work is a beautiful, positive, additive thing, or whether it’s an energy drain.

Has your sobriety impacted that process?

I feel incredibly lucky that I got sober when I did. It wasn’t like a clear-cut, clean cut. But I think 27 was when I started really thinking about it and considering it. Most of my music career was very, very local, happening within this five-mile radius, basically up until Covid. And by the time I was out in the world — touring internationally, really pushing my body athletically at my shows, going to fashion events, going to film events — I was walking into those situations knowing that I was going to be completely in control. I wasn’t gonna say anything that I regretted, and I was gonna be able to wake up in the morning and feel decent. It’s completely a superpower. I’m definitely not one to ever push sobriety on anyone else, but it’s nice to feel like a part of the club. One of the other things is there was a great fear that came with it. Maybe the thing that made me the artist I was was that self-destructive streak. This fear that if I got sober, or if I started taking care of myself, I wouldn’t be able to write songs anymore.

You mention that on “Coping on Unemployment,” in one of those conversational lyrics: “I think your music got worse since you went fully sober/At least now you won’t kill yourself.” Did someone actually say that to you, or was it more of an internal battle?

That line is something that I said to myself. As I was struggling to write that very song, I was sitting there, slamming my head against the wall and saying, “I have nothing to say. What is going on?” It was a moment of a sort of dark fantasy about sitting in a version of myself, berating myself for not having the courage to continue to torture myself. It’s very backwards that way.

As much as this album is about how your relationships have impacted you, it’s also about how you’ve impacted other people, and putting those traumas into conversation with one another.

I’m happy you picked up on that, because a lot of the album is about struggling to communicate — getting a little bit older and taking more account of the ways in which I communicate. When you’re a kid, it’s easier to romanticize some level of aloofness or mystery. Then you get older. In my experience, I have felt more inclined to just really, really, really be clear with people. In turn, that’s allowed for a more honest experience for myself. To your point, I think the two are a bit in conversation. We learn so much in talking and sharing and being vulnerable with other people.

Best of Rolling Stone