Is Calgary's approach to curbing social disorder paying off? There are signs of progress, but it's complicated

Karen Barry was once skeptical whether anything would get rid of the drug use and parties happening in the back alley behind her business.

Encampments, fights, waste bins strewn across the parking lot — the owner of Beltline Cannabis has seen all sorts of "problematic" behaviour, which she says is bad for business.

Sometimes she would call 911, but she knew police resources were regularly stretched thin and the problem would often not be solved. Other times she'd resort to confronting people herself — something she admits was not advisable — but the feeling of helplessness would sometimes drive her to it.

"Because after 10 years of experiencing what I had experienced, I was not positive that really anything was going to improve it," she said.

"This business is my family. So like any good mama bear, you're going to protect your family."

Barry's encounters are far from unique.

Over the course of the pandemic, police numbers show social disorder increased significantly — such things as noise complaints, reports of suspicious activity or a potential mental health concern.

As people have returned to downtown in the past year, media reports of disorder and crime revealed a chaotic situation, especially around CTrain stations, where the city recently announced plans to ramp up security.

Earlier this year, the province also dedicated 12 sheriffs to address the problem of downtown safety. Following a multiple stabbing incident downtown this week, Premier Danielle Smith made a funding pledge for 100 more officers between Calgary and Edmonton.

At the same time, new data suggests there's progress in some areas. Calgary Police Service figures show a decrease in overall reports of social disorder downtown and across the city in 2022 compared with the average of the preceding four years.

Social disorder numbers reflect public perception of crime and safety because it is based on reports of suspicions of potential crime rather than specific crime that police will investigate.

Social disorder reports citywide

There's no single reason for the decline in those social disorder calls.

Police say the drop is due to a multitude of factors, including reversion to the norm after a pandemic increase, redirection of calls from 911 to 211, and the use of alternatives to police attendance such as outreach and mental health workers.

Calgary police also reclassified a number of types of reports out of the social disorder category.

Still, police say the statistics show the city is making headway in its efforts to provide a whole-community approach that includes social service providers, and not necessarily police, when dealing with its vulnerable population.

At the same time, violent crime in the city centre was flat compared to the five-year average while there was an increase further out.

Property crime was essentially flat for the same period, according to Supt. Scott Boyd, who is in charge of the Calgary Police Service's community policing patrol division.

Downtown outreach program diverting calls

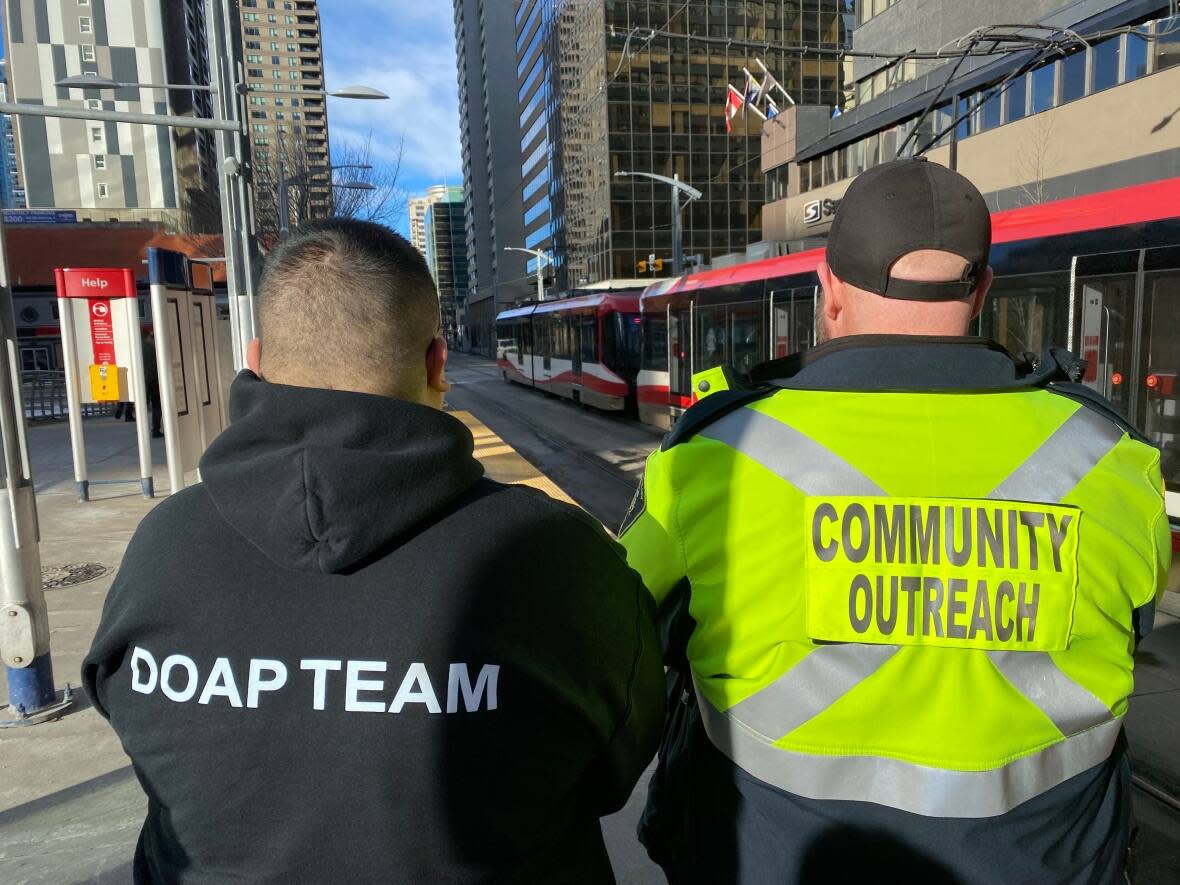

Calgary police say one of the biggest impacts on the number has been a pilot program established with Alpha House known as the DOAP team.

DOAP stands for Downtown Outreach Addictions Partnership. It is a collaboration between CPS and Alpha House where an outreach team responds to calls as an alternative to police.

The project started last August in several core neighbourhoods referred to by police as Zone 1, which includes Chinatown, Downtown Commercial Core, Downtown East Village, Downtown West End, Eau Claire and the Beltline.

CPS officials say it has likely contributed to the decrease in direct calls to police.

"It's an alternative to street level disorder, addiction experiences, homelessness, complex needs mental health — those types of pieces," said Charlene Wilson, director of programs at Alpha House.

"So the teams are responding out to provide the right response."

Annual reports of social disorder in Zone 1

Those responses could include transport to a safe place, a family connection, a safe consumption site, shelter, a clinic or hospital. The team also has a mobile shelter that can provide a temporary safe place for people with nowhere else to go.

Outreach workers are often equipped with personal hygiene and medical supplies, which police do not have.

"I equate it to you're trying to frame your house and you don't call a plumber to do that work," Boyd said in an interview last month. "You're gonna call a carpenter to do that work. You might need a plumber later."

Change in social disorder reports

The public can request an outreach worker's response either through calling Alpha House's teams or through 211,a number similar to 911 but connected to a network of community, social, health and government services instead of EMS, fire and police.

Recently, the City of Calgary co-located its 211 call centre with its 911 call centre, so 911 calls not requiring EMS, fire or police can be directed to 211.

The result is a team approach between social services providers and police. The right resource is directed at the appropriate problem. Boyd and Wilson say this improves outcomes for those needing help.

For members of the public like Karen Barry, it has made a difference.

"Communication between our police services and the DOAP team and other social organizations appears to be working," she said, noting her 911 calls have decreased to zero in recent months.

Yet there are other business community leaders who believe many of the services offered via 211 and outreach workers are still a Band-Aid solution. Some will argue what's needed is treatment beds and true mental health care for vulnerable people. There are also calls for an even greater police presence in the city's core.

Social disorder and feeling safe

Police social disorder figures represent a kind of catch-all category of calls for police service that are not necessarily reports of an actual crime. They include calls about suspicious people or vehicles, unwanted guests, disturbances, mental health concerns, noise and party complaints, intoxicated people, drugs, possible gun shots, indecent acts, speeding and prostitution.

That means the CPS numbers are report-based rather than based on an arrest, charge or conviction. When the public reports something, police log it under various different categories.

Wilson, with Alpha House, and Boyd, with CPS, both say social disorder numbers reflect the public's sense of safety and are a perception of potential for crime or lack of safety.

In 2022, calls for suspicious vehicles and people were down by nearly 7,000, which represents about a 20-per-cent decrease from the preceding four-year average.

Monthly social disorder reports in the 5 neighbourhoods with the greatest numbers

That was offset by increases in mental health and disturbance calls, collectively increasing by more than 3,000. The mental health calls were 32 per cent above the four-year average in 2022.

Many of the calls of this nature are related to public perceptions of safety, which ironically is often in response to a vulnerable person's efforts to find safety, according to Wilson. This is why Alpha House has gone to such lengths in educating local businesses in areas that experience elevated levels of drug addiction and homelessness.

"The community can be one entity, we can come together and make sure that everybody is a part of the community and a solution to safety," she said.

Returning downtown to a mental health crisis

Robert Schuett, a lawyer who lives and works in the Beltline, has seen firsthand how the wider mental health crisis is expressed on the streets. He lives on 17th Avenue and walks daily to his office on 11th Avenue.

As the streets emptied of traffic and people, he noticed how people who spend most of their time on the street were able to spread out.

"Following the pandemic — so let's say, like, late pandemic 2021 — I think you saw a real rise," said Schuett.

"Maybe it hasn't gone up further, but you definitely notice; it's definitely something that's in your face."

Wilson says the number of calls they have received have remained more or less constant over time, ranging from 90 to 120 calls per day. But what has really changed in recent months has been the number of people who are downtown.

"A lot of things closed for three years. So has it increased, or have we just been exposed again to the realities of a complex issue?" Wilson said.

"I would say in the colder months, we do see skyrocketing calls, like we can't keep up. We've had to expand our programs in order to stay in front of it," she said.

Conversely, calls to police tend to increase in the summer months, which is often the time when more people are out in neighbourhoods like the Beltline, according to Boyd.

And while social disorder calls to police are down, certain areas have seen an increase in calls, namely to Calgary Transit stations.

Complete numbers for 2022 are not yet available, but CPS shared figures up to the third quarter. They show a 12-per cent increase of crime and calls for service compared to a three-year average.

In the first half of the year, calls were up more than 50 per cent compared with the three-year average.

Making the right call

Some of the most important indirect work of the DOAP team pilot has been to encourage the community to work together.

That involves working with the city's vulnerable population and the wider community through education, Wilson says.

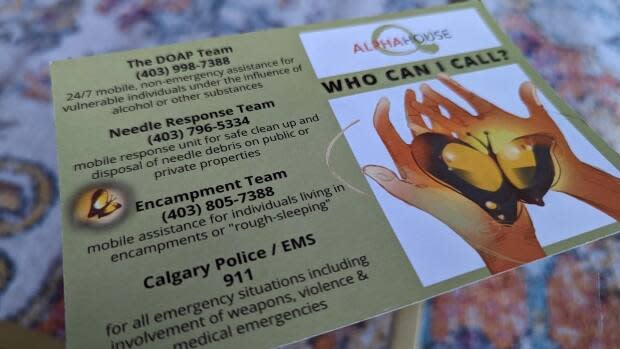

Alpha House hands out leaflets saying "Who can I call?" with the numbers for the DOAP team, needle response units, an encampment team and police or EMS.

"I have the DOAP team's cell number. They have come out. I delivered a machete to them in the past," said Barry, the business owner, who noted it took several visits from the team before she was convinced it was a more effective response.

Schuett says knowing who to call could be vitally important to getting someone undergoing drug and mental health issues the help they need.

"I don't think the police do a very good job at handling circumstances like that," he said.

Barry says knowing how to respond to something she sees in the streets comes down to having the power to help. Calling 911 might force people to move but there are more powerful responses that help with the whole community's safety.

"Power is galvanizing the community to create a grassroots improvement program."