Central Coast elephant seal pup swam 5,000 miles to Alaska and back. See her surprising journey

Researchers don’t often put electronic tags on elephant seal pups. At more than $3,000 per satellite tag, losses are just too high to risk the expensive technology.

But in one recent case, it paid off big time.

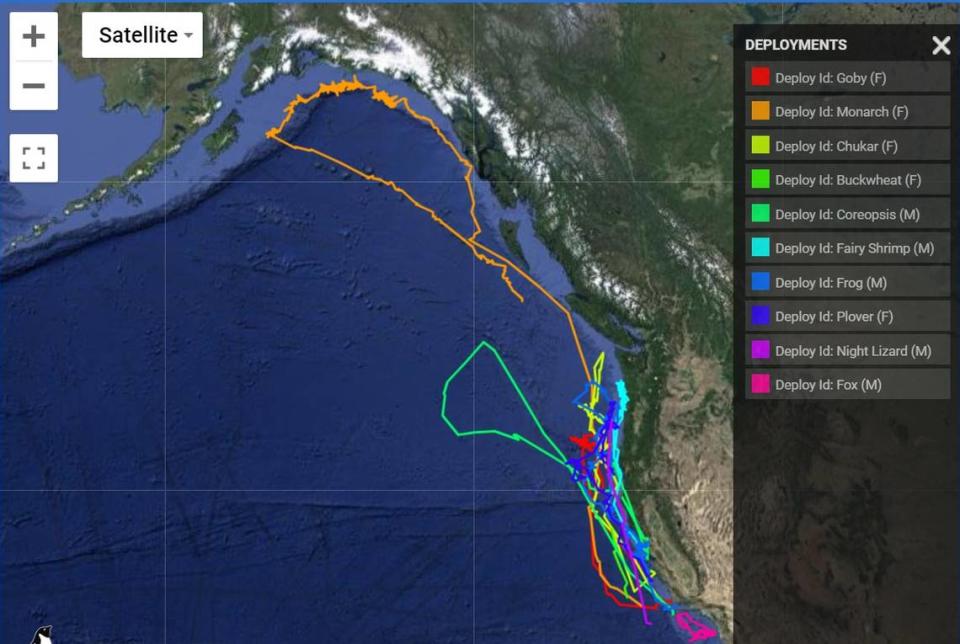

One tagged pup not only survived, she returned to the Central Coast with new and exciting data showing a journey that stretched nearly 5,000 miles, spanning the entire West Coast all the way up to Alaska — far beyond what the Cal Poly researchers tracking her exploits previously believed a young pup could travel in its first migration.

Now the pup, nicknamed Monarch, is resting peacefully back on the Vandenberg Space Force Base beach where she was first tagged, and the researchers are left to analyze the data from her surprising journey.

Cal Poly researchers tag 10 seal pups to examine migration habits

Elephant seals are migratory, with the adults swimming north along the coastline as far as Alaska and out into the northern Pacific.

After they are weaned — and have spent a month on the beach working on their breath-holding and swimming skills — the pups will also venture out. They can’t live off the blubber they gained while nursing forever, after all.

Weaned pups make their first migration alone, without adult guidance. They leave the beach in the spring, and those that survive return in the fall. Without guidance, pups somehow find their way.

Although pups haven’t before been tracked on that first migration, the accepted wisdom was that they didn’t get as far as adults on that first migration.

Cal Poly associate professor Heather Liwanag’s research set out to see how far they did go. They learned that while most don’t get that far, at least one did.

Katie Saenger, one of Liwanag’s master’s students, tagged five pups at the Vandenberg Space Force Base beach and five pups on San Nicolas Island off Ventura County in April 2023. Their electronic tags allowed the researchers to follow the pups in real time.

The researchers chose nicknames for the seals from local wildlife like Frog, Plover and Goby. Monarch’s name turned out to be especially apt; Monarch butterflies are also long-distance migrators.

Nine of the pups stayed conservatively close, migrating along the California-Mexico coast.

The team retrieved a device from one at King Range National Conservation Area, near Cape Mendocino in Northern California, and one from Año Nuevo, north of Santa Cruz. Another was tracked to San Francisco Bay, but the beach he hauled out on in the Farallon Islands was inaccessible to humans.

Monarch swam north and kept on going.

Central Coast elephant seal pup swims to Alaska

Like other elephant seals, Monarch didn’t swim across the surface. She dove down and came back up, making forward progress. Females like Monarch are believed to also feed along the way, snapping up small fish.

Team members and other elephant seal observers watched her progress with excitement: She was doing so great! Going farther than previous research led them to believe pups would travel. Go, Monarch!

The up-and-down zig-zagging readings coming from the tracker indicated that she was finding food in those cold Alaskan waters, even far out to the edges of the Aleutian Islands, nearly to Russia.

On Oct. 5, 2023, after six months at sea and about 2,600 miles away from the beach where she was born, Monarch turned south and headed for California.

All seemed fine until Oct. 26 when Monarch’s transmitter went silent. The bad news for seal pups is that usually means they met their fate in the jaws of a white shark. Thus goes the cycle of ocean life.

But not this time. The transmitter’s battery had failed, but Monarch hadn’t. She was still swimming back.

Monarch returns to Central Coast beach — 73 pounds heavier

A scientist taking a bird survey saw her on May 12, hale and hearty.

Julie Howar, senior marine ecologist and a Geographic Information System specialist from Point Blue Conservation, was performing bird surveys at Vandenberg when she saw two elephant seals wearing transmitters on their heads on the beach.

One was this year’s weanling, Aurora, who had not yet left the beach after being tagged in April. The other was a juvenile.

Identifying elephant seals is a challenge. Because they molt their skin every year, dyed marks fall away with the skin.

This young seal had no dye marks, but she had a flipper tag that was partially visible. Howar used her spotting scope to take a photo. She was able to read a couple of digits on the seal’s flipper tag and reported the sighting to Liwanag.

It was Monarch.

“It was amazing that Julie knew what to look for and reached out to me,” Liwanag said.

Surviving the first migration is significant, since only about half of the pups do. They usually gain little, if any, weight. Monarch went a step better: She gained 73 pounds. The fishing in Alaska was good it seems.

“We were so excited when we figured out it was her,” Liwanag said. “She is the first seal to demonstrate that weanlings can go as far as Alaska, which we did not expect.”

Cal Poly team recovers elephant seal’s tag on Central Coast beach

The Cal Poly researchers then pulled together a team to retrieve the devices on Monarch’s head and back.

The pups got satellite and Very High Frequency (VHF) radio transmitter tags. The satellite tag was zip-tied to a polyester mesh glued to the seal’s head with marine epoxy.

That tag sends signals to the satellites when the seal comes up for a breath and her head is out of the water. The batteries on Monarch, and other seals in that 2023 cohort, ran out of juice and stopped transmitting, which implied the young seals may spend more time at the surface than adult seals, running the batteries down. The researchers adjusted for that possibility in their next cohort by programming tags to transmit less frequently, extending battery life.

Meanwhile the VHF radio transmitter was zip-tied to polyester mesh on the seal’s back.

“We use that to home in on the exact location on the beach,” Liwanag said. “We only want to hear that signal when the seal is completely hauled out.”

Those polyester mesh patches will fall away as the seals molt their skin, putting the researchers at a time crunch.

“That’s why we hustled down there to retrieve her tags as soon as we could,” Liwanag said. “She was in the process of molting off those patches, and we were worried that the tide might take the tags away if she molted them onto the beach.”

Saenger led the team, since Monarch is part of her thesis project. Liwanag and graduate student Maria Lopez-Neri joined, along with veterinarian Heather Harris and veterinary technician Lauren Campbell from The Marine Mammal Center and Vandenberg biologists Rhys Evans, Nick Todd and Zia Walton.

“Accessing the beach at Vandenberg is always an adventure,” Liwanag said.

Todd is an experienced climber, skills he uses as an ornithologist specializing in falcons. He guided the group in setting up a rope to help them climb the bluff to the beach.

“The last part is especially steep, and it’s best to move down backward — not quite rappelling, but definitely not just hiking,” Liwanag said. “It is a challenge to get our team and all our gear down the hill (and back up), especially with our heavy weighing gear.”

A safe dose of sedative calms the animal to allow researchers to handle her safely, without endangering the seal. But the amount of sedative needed is based on the seal’s weight, and weighing a seal involves a tripod with a scale. The seal is lifted in a tarp to be weighed.

Nothing involving elephant seals is easy.

On the beach with the seal, The Marine Mammal Center veterinary team, Harris and Campbell, administered the sedative and monitored the seal while she was sedated during the tag removal. Monarch was cooperative enough that the team could weigh her before they gave her the injection.

The zip ties were cut. Success! Devices in hand.

What did researchers learn about elephant seal migration?

Back at the lab, they downloaded the data. Preliminary results showed Monarch dove as deeply as 600m (2,000 feet), with many dives between 400m (1,300 feet) and 500m (1,600 feet) deep.

“These are impressive dive depths for a young seal pup,” Liwanag said.

Saenger’s master’s thesis project focuses on that first foraging migration of newly weaned northern elephant seals.

The paths reported by the tracking devices map out where they travel, which can then be related to ocean factors that adult seals are known to use to navigate, such as sea surface temperature, the ocean floor — including the Alaskan coastal shelf and the seamounts along her return trip — and productivity.

That data will help researchers to better understand the path pups take during their crucial first migration.

“We simply don’t know where these seals go on their very first migration, or how they decide where to go,” Liwanag said.

Other possible influences are whether the seal is born in a new or an established rookery, and whether they are male or female. Adult female and male seals migrate to different places, with different foraging strategies.

“We know the adults have very different migration patterns between males and females, but we expect that these differences may not be as pronounced at this age,” Liwanag said. “So far, we see that there is a lot of individual variation in migration patterns. This makes sense, because the seals have to find their own way with no instruction from anyone. They don’t learn from their mom, and they don’t travel together.”

After removing the devices, the team watched over Monarch until she recovered from the sedative.

“Monarch moved back near her original napping spot and seemed to be doing just fine,” Liwanag said.