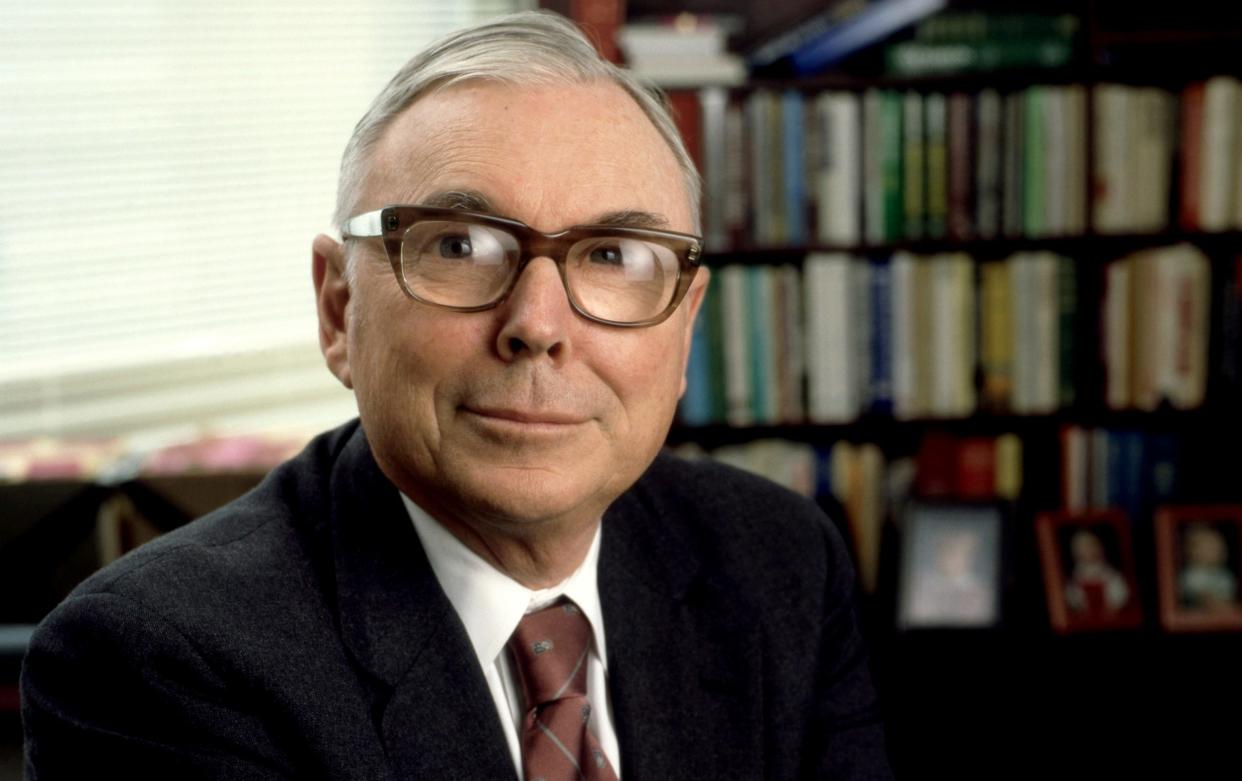

Charlie Munger, billionaire investor who worked alongside Warren Buffett for more than half a century – obituary

Charlie Munger, who has died aged 99, was right-hand man for more than 50 years to Warren Buffett, the multi-billionaire investor nicknamed the “Sage of Omaha”; as vice-chairman of their hugely successful investment conglomerate, Berkshire Hathaway, Munger, though lower-profile, was certainly as revered by loyal shareholders as his more famous colleague.

Under their stewardship the company, originally a textile manufacturer, became a multinational investor wholly or partially owning some of the largest companies in the US and around the world. Subsidiaries include the Kraft Heinz Company, Dairy Queen and Fruit of the Loom, while the company also holds significant stakes in Coca-Cola, Wells Fargo, IBM, American Express and Mars.

Buffett and Munger were credited with popularising and amply demonstrating the concept of “value investing”, inspired by Benjamin Graham’s book The Intelligent Investor, whose aim is to buy well-managed, often rather dull, companies that look cheap relative to their long-term earnings potential, and to hold them for the long term. The duo favoured banks and insurers as well as established consumer brands, always with “able and honest managers”, and shunned fashionable high-risk investments in the digital and bioscience spheres, making an exception only for Apple.

Berkshire Hathaway’s consistent outperforming of the US stock market over many years turned both men into billionaires, and their modus operandi was deceptively straightforward. After discussions, they would typically put investment possibilities into three baskets: Yes, No or “Too tough to understand”.

Buffett said: “Charlie and I look for companies that have a) a business we understand; b) favourable long-term economics; c) able and trustworthy management; and d) a sensible price tag. We like to buy the whole business or, if management is our partner, at least 80 per cent. When control-type purchases of quality aren’t available, though, we are also happy to simply buy small portions of great businesses by way of stock-market purchases. It’s better to have a part interest in the Hope Diamond than to own all of a rhinestone.”

The pair became cult figures, academics, professional and DIY investors picking over their words, delivered in open letters and at Berkshire’s massive annual shareholder meetings. These events, held in both men’s native Omaha, Nebraska, grew over time to stretch to an entire weekend, nicknamed “the Woodstock of capitalism” and broadcast live on the internet.

As well as such entertainments as giant picnics, live music and competitions such as the “newspaper-tossing challenge”, the meetings featured marathon Q&A sessions, likened to a comedy double act, at which the pair would munch chocolates while dispensing folksy homilies on everything from Goldman Sachs to the importance of good financial education at school, and from the threat of Google’s self-driving car to corporate governance.

The chemistry between Buffett and Munger, competing with pithy one-liners, drew large crowds, and audiences particularly relished Munger’s gift for acerbic put-downs. The stock market, he once claimed, was populated with innovators, imitators and “swarming incompetents”; cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin were “a financial product invented out of thin air… contrary to the interests of civilisation [but] useful to kidnappers and extortionists”, while bankers were little better than “heroin addicts”, unable to control themselves.

In a 1995 speech at Harvard, Munger set out 24 “standard causes of human misjudgment” in investing (and everything else), ranging from simple concepts such as denial – “The reality is too painful to bear, so you just distort it until it’s bearable” – to the more complex, such as “bias from over-influence by social proof”, an example being when the giant oil companies Exxon and Mobil each bought fertiliser companies simply because the other had.

For amateur investors, Munger championed the use of “investment checklists” and published an “almanack” which included such advice as: “Only in fairy tales are emperors told they are naked. To be objective you must have independent thoughts”; “Acknowledging what you don’t know is the dawning of wisdom. Stay within your ‘circle of competence’”; and “A great business at a fair price is superior to a fair business at a great price.”

In Working Together: Why Great Partnerships Succeed (2010), Michael Eisner, the former chief executive of Walt Disney, hailed Munger as the “unsung hero” of America’s most famous investment fund, observing that his natural pessimism was a healthy antidote to Buffett’s more buoyant optimism: “If Charlie only hates a project, as opposed to despising it or getting physically ill over the idea, then they will go forward.”

Buffett once described Munger as his “canary in the coalmine”, and in 2014, when he admitted in his annual letter to shareholders to an investment that lost him nearly $900 million after he failed to consult Munger, a chastened Buffett wrote: “Next time I’ll call Charlie.”

The son and grandson of lawyers, Charles Thomas Munger was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on January 1 1924. Although he did not know the young Warren Buffett, who was seven years his junior, he grew up 200 yards from Buffett’s home and during the Depression worked in Buffett’s grandfather’s grocery store.

Munger enrolled at the California Institute of Technology to study mathematics, but the outbreak of the Second World War meant that he could not finish his degree. During the war he served as a meteorologist in the US Army Air Corps, then used family connections to enter Harvard Law School, where he graduated in 1948.

He then moved to Los Angeles to work for a leading law firm that represented such wealthy entrepreneurs as J Paul Getty. In 1962 he co-founded the Los Angeles-based firm of Munger, Tolles and Olson.

In a 1984 essay Buffett described his first meeting with Munger: “I ran into him in 1960 and told him that law was fine as a hobby but he could do better.”

In parallel with his law firm, Munger established a partnership for a group of investors which, between 1962 and 1975, produced annual returns of around 20 per cent against less than 5 per cent for the Dow Jones Industrial average.

In an annual report for Wesco, a mutual savings association that Munger led before Berkshire took it over, he wrote: “It’s remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

He started working with Buffett in the 1960s, sometimes spotting promising investments for Berkshire Hathaway, and the pair became formal business partners in 1978, when Munger became vice-chairman of the company.

Buffett was a Democrat, while Munger was a Republican, though he was a strong supporter of population control and abortion rights. He had an estimated fortune of some £2 billion (dwarfed by Buffett’s £80 billion) and gave much away to causes such as Planned Parenthood.

In later years the question of succession was one that came up with increasing frequency at Berkshire’s annual shareholders’ meetings, but which the two friends were sometimes reluctant to face head-on. The 2014 event opened with a film in which Buffett performed a duet with singer Paul Anka to the tune of My Way: “I pray each day / For Charlie Munger / Who needs the gym / When next to him, / I feel younger?”

By 2020, however, Buffett was prepared to admit that “Charlie and I long ago entered the urgent zone.” Although Munger remained vice-chairman of Berkshire until his death, two other vice-chairmen, Greg Abel and Ajit Jain, have day-to-day oversight of Berkshire’s businesses.

Munger’s first marriage, to Nancy Huggins, ended in divorce. They had two daughters, and a son who died of leukaemia aged nine in 1955. In 1956 he married Nancy Barry. She died in 2010 and he is survived by their three sons and a daughter, by two stepsons and by the daughters of his first marriage.

Charlie Munger, born January 1 1924, died November 28 2023