The Coal Industry Is Wiping a Historic German Village Off the Map

(Bloomberg Markets) -- The village of Mühlrose in Germany’s far east has stood since the 13th century through wars, fires, unscrupulous lords, the division of the country and its reunification. Now its 200 people are packing up and leaving because of an industry they thought was also being consigned to history. Mühlrose will be wiped off the map to make way for a coal mine.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Saudis Warned G-7 Over Russia Seizures With Debt Sale Threat

Microsoft Orders China Staff to Use iPhones for Work and Drop Android

S&P 500 Holds Gains as Fed Bets Steady on Powell: Markets Wrap

Biden’s Biggest Donors Left Powerless to Sway Him to End Bid

Only a few signs of the village’s once-fierce resistance remain. “Rescue our beautiful Mühlrose,” reads a flyer on a red brick home, its windows closed and shuttered.

One of the town’s last residents, Detlef Hottas, lives in a farmhouse with his wife, plus a few sheep and chickens. At 64, he rides along the deserted streets in an electric wheelchair before he, too, must relocate by yearend. “I didn’t want to resettle, because I was born here,” he says. “This is my home.”

Mühlrose lies in the region where the Czech Republic, Poland and former East Germany come together, the center of communist Europe’s coal mining. Rather than a symbol of a bygone era, though, it’s the latest example of how the continent is struggling to ditch the dirty fuel after Russia’s war in Ukraine upended energy supplies.

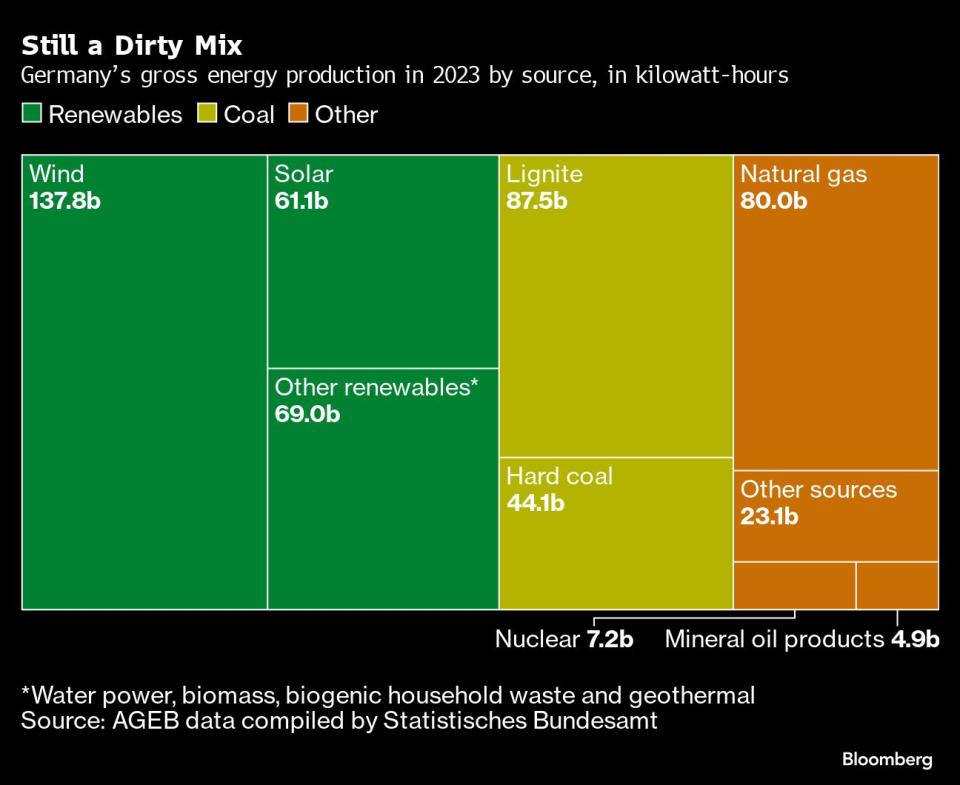

Germany, whose governing coalition includes the environmentalist Green Party, wants to speed up plans to abandon coal altogether as more renewable energy sources are added to the mix. But Europe’s biggest economy has relied heavily on the fuel for electricity production after gas from Russia was halted and it stuck with a plan to switch off its nuclear reactors.

The result is that a giant, opencast coal mine is closing in on Mühlrose as power generation company Lausitz Energie Bergbau AG, or LEAG, expands. It will excavate lignite, low-grade so-called brown coal.

Demolition work was in full swing in late June. The digging has eliminated more than two-thirds of the buildings. Only a few houses remain amid “no trespassing” signs. The steam from the cooling towers of the power plant that the coal feeds rises on the horizon.

“For me, it’s simply unbelievable,” says Jadwiga Mahling, a Protestant pastor who’s lived in the parish for about a decade. “Everyone speaks about the energy transition, but here we are purely deciding in the interest of business.”

Martin Klausch, the LEAG official in charge of the resettlement, says the company has done all it can to ease the transition for those in the town. “We don’t want anyone to be financially worse off as a result of the relocation,” Klausch says.

Countries do want to get rid of coal, especially the more polluting lignite variety. Even in Poland, the European Union’s most coal-reliant economy, the government has agreed to a transition with powerful mining unions, albeit a slow move to a total phaseout by 2049.

The issue is timing, especially when far-right parties are gaining ground by amplifying popular fear over the cost of the EU’s package of green initiatives.

The German government reached a deal with coal giant RWE AG to stop using the fuel by 2030, eight years ahead of schedule, which will save more villages from the excavator.

But LEAG, part of Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinsky’s empire, wants access to the coal under Mühlrose before it gets out of the industry. The company submitted its mining application in March, and the state regional authority says it’s assessing it.

Germany’s economy and climate action minister, Robert Habeck of the Green Party, told a press conference in Berlin in early June that lignite had secured the country’s wealth in the past but its time is coming to an end. Yet there’s little he can do because of contracts signed by the previous government with mining companies that now hamper political efforts to get rid of coal.

Instead, Habeck announced an aid package for LEAG in line with an earlier agreement: at least €1.2 billion ($1.3 billion) to cover the cost of job losses and the restoration of the land after mining ends, but by the original target year of 2038.

Habeck is hoping market forces will spur an earlier exit, as falling power prices and rising costs for polluting the environment make it increasingly unprofitable to burn the fossil fuel in Germany. Josephine Semb, a researcher at Europe University Flensburg who co-authored a study on lignite mining published in late June, says mining under Mühlrose would be uneconomical.

LEAG says otherwise. The company is calculating with different scenarios for its lignite business, according to Chief Executive Officer Thorsten Kramer. “We assume that we will continue to generate income until 2038,” he says.

There have been few protests like those that flared up last year in other parts of Germany. RWE drew the wrath of activists when it decided to raze a final village in the Rhineland. A high-profile standoff ensued involving Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg.

Mühlrose, which once housed 600, will be the last village to be swept away. It was a long time coming. After World War II, the communist government in the former East Germany decided to build almost its entire energy program on lignite. First, Mühlrose’s cemetery had to make way for mining in the 1960s, then more of the village succumbed to it.

The last of the brown coal exited that pit in 1997. Residents thought the days of mining were over. But a decade later, Swedish utility Vattenfall—the owner of the mining operations at the time—decided otherwise and announced plans for an expansion.

Five years ago, a majority of Mühlrose residents voted to move away, after almost three decades of struggle over lignite expansion, according to Robert Sprejz, the mayor. “It was their wish to resettle,” he says. “They simply had enough of the noise and dust. At the height of operations, our windows had to be cleaned almost daily.”

About half of the inhabitants have moved to a resettlement site, called Mühlrose-neu, a short drive away, part of the village of Schleife.

LEAG expects to take ownership of all the land by the end of this year and start digging in 2029. Should the mining authority approve the destruction plans, the forest owners will lodge a legal complaint, says René Schuster, an activist with the environmental group Green League.

While there were court victories against lignite plans in the past, “the rulings often came too late,” Mahling, the pastor, says. “Then we would know that what was done was illegal. But the village and forest are anyway gone.”

At the end of June, Mahling, in her flowing black clerical robe, held a makeshift outdoor church service in the last strip of trees near the lignite mine, next to the road that will bear mining trucks by yearend.

Environmentalists joined to honor a few holdout forest owners seeking to challenge LEAG. A small table draped with a white cloth served as an altar on the grass. The churchgoers, some in shorts and T-shirts, sat on benches once used in a beer hall. The trees around them were already gone, with machines hacking through the stumps and roots.

Villagers are now resigned to the loss of Mühlrose, a stronghold of the ethnic Sorb minority in Germany. Numbering only 60,000, Sorbs are descendants of Slavic tribes that lived in this region of Lusatia, sometimes called Sorbia.

A Sorb herself and the daughter of a Protestant pastor, Mahling speaks Sorbic and offers bilingual services. She officiated at the funerals of the last Sorb women to wear traditional dresses, white lace adorned with bright-colored flowers. It reminded her of a local saying: “God created Lusatia, but the devil made the coal underneath.”

--With assistance from Maciej Martewicz.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

At SpaceX, Elon Musk’s Own Brand of Cancel Culture Is Thriving

How Stocks Became the Game That Record Numbers of Americans Are Playing

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.