David Bowie Couldn’t ‘Cope’ With Being Himself—So He Became Ziggy Stardust

“DAVID BOWIE IS ZIGGY STARDUST” the press release from RCA Records blasted out to the world on June 16, 1972. With the eventual breakout single “Starman” already percolating on the U.K. charts, and after eight years mostly spent in the showbiz wilderness, David Bowie was about to become a global superstar. Bowie had conceived The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars in the autumn of 1971, initially as “a concept of the life cycle of a rock and roll star.” Recording sessions soon commenced at Trident Studios in London, hot on the heels of Bowie’s fourth album, Hunky Dory.

“Two weeks after completing Hunky Dory, David was in Trident and said, ‘We’re going to record another album,’” Ken Scott, the co-producer on both albums, recalls. “I said, ‘You’ve got to be joking. We’ve only just finished Hunky Dory. It’s not even out yet.’ He explained, ‘They want me to have another one in the can. But you won’t like this one. It’s more rock ’n’ roll.’ And he was proven wrong. I loved it!”

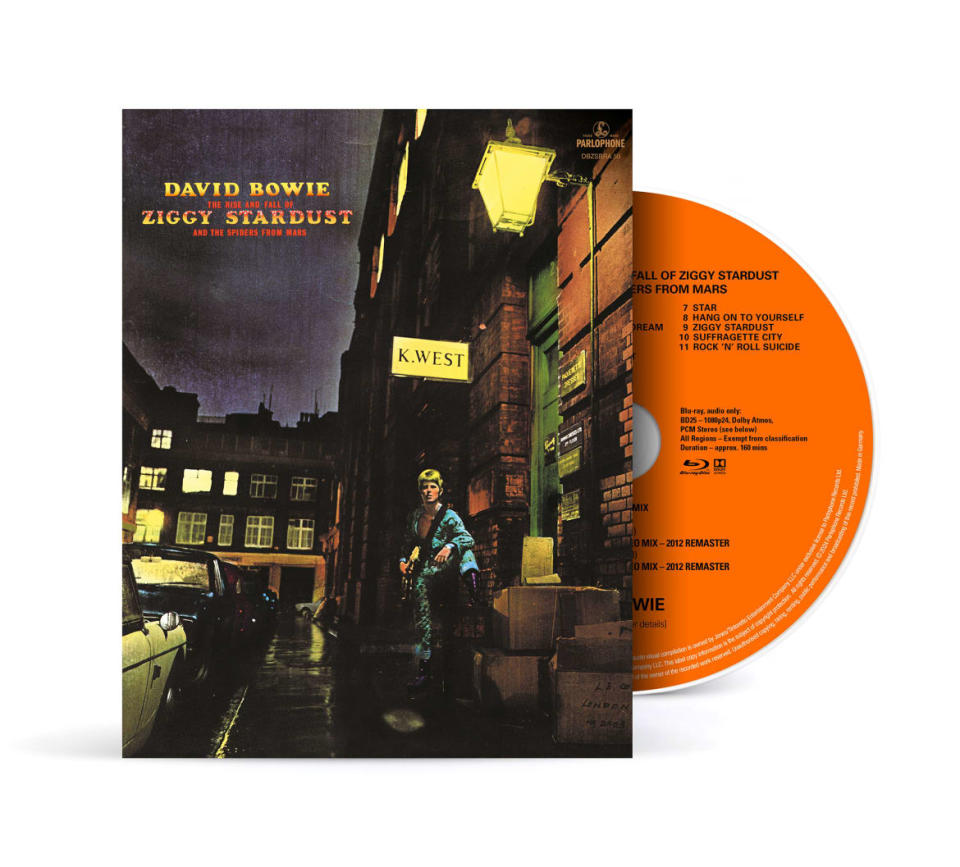

But unlike the focused, economical sessions of its predecessor, the making of Ziggy Stardust was evolutionary, as is illustrated on the new five-CD box set Rock ‘n’ Roll Star, out on Friday. In fact, there are so many tracks included on Rock ‘n’ Roll Star—121 in total, across six discs—because the Ziggy Stardust track listing would be in a continual state of flux. As fans have already heard on the recent Record Store Day release Waiting In The Sky, compiled on Dec. 15, 1971, Bowie drew up an early version of Ziggy that included a re-recording of the January 1971 single “Holy Holy,” Chuck Berry’s “Round And Round,” Jacques Brel’s “Amsterdam,” and his own “Velvet Goldmine.”

Following David Bowie to the World’s Most Exclusive Garden

With his brief coming into focus, Bowie gave up on the idea of writing songs for others—like his flamboyant designer friend Freddie Burretti and the side project he’d christened The Arnold Corns—and reclaimed them. Thus, Ziggy Stardust began taking shape, with Bowie rewriting lyrics around the loose idea of an androgynous, alien rock star coming to Earth before an impending apocalyptic disaster to deliver a message of hope. Along the way, he referenced stolen guitars and his own band, soon to be called the Spiders From Mars.

“That was the big struggle: wondering if I should try and be me. Or, if I couldn’t cope with that, then make up some people. Would I be them easier?” Bowie recalls in the liner notes to the box set of the early Ziggy days, which would presage the character-hopping that would eventually come to define his career. “And that’s how Ziggy got started, you see. Well, if I don’t like being David Jones, then we’ll think of someone else [to be] for a bit.”

Bowie’s label RCA thankfully—in hindsight, at least—rejected the January ’71 version of the album, on the grounds that record execs didn’t hear a single.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

“The label, of course, had said, ‘Look, we need one more track. We need a hit,’” Bowie’s lifelong friend Geoff MacCormack, whose book Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me chronicles his relationship with Bowie in intimate photos and recollections, remembers of the birth of “Starman.” “That’s when he wrote it, which put him on British television and which outraged everybody, because it was so camp. But to be able to do that at the last moment, and produce a hit—which was spot-on and exactly what they wanted—that’s where his head was at. He had plenty of ideas in reserve. His headspace was comfortable at that point. He wasn’t stressing about it.”

Still, responding to RCA’s request for a hit single, Bowie labored to get “Starman” just right, as the five versions on Rock ‘n’ Roll Star show.

And so, tracks like “Sweet Head” and “Velvet Goldmine” were jettisoned in favor of “Lady Stardust”—previously a contender for Hunky Dory—as well as several songs that had yet to be written. Unbowed, Bowie quickly came up with the driving “Suffragette City” and “Hang On to Yourself,” as well as “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide” and the all-important “Starman,” both of which would tighten up—if not downright create—the overarching themes of Ziggy Stardust.

“I changed the words [of “Hang On to Yourself”] to fit the idea of the central character of the album, Ziggy Stardust,” Bowie recalls in the liner notes to the box set. “And I wrote it to revolve around his group’s attitude to him as he was becoming cited as a star, and they were being left out of things.”

“David was on fire creatively at the time,” MacCormack recalls of the remarkably brief period in which Bowie made both Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust. “He hadn’t been able to replicate the success of ‘Space Oddity,’ and he was enormously frustrated. That hit disturbed him more than anything in his professional life because after that, there was nothing. And it even sounds kind of like a one-hit wonder. … But that turned out to be hugely beneficial, because out of his frustration came this explosion of ideas and songs and creativity. And Ronson was involved, so there was that toughness and that urgency.”

“Mick Ronson was absolutely essential,” Scott adds of the Spiders From Mars guitarist. “He was in David's brain. He was in my brain. Sometimes, before anything was even requested of him, he'd say, ‘I know what to do,’ and go down and do it, first take. He knew what we were after even without us having to say.”

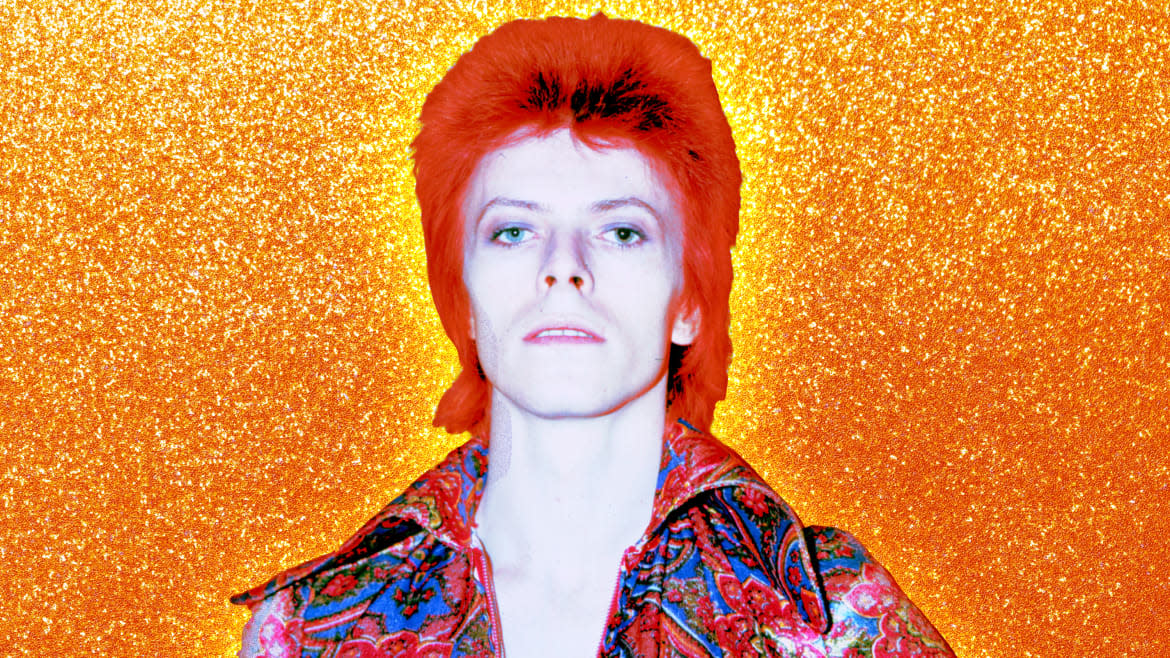

Meanwhile, as the album Ziggy Stardust evolved, so did the character. Bowie changed his appearance, chopping off the long locks of his Hunky Dory days and dying his hair bright red. Soon, Bowie was ready to unleash Ziggy Stardust. But with Hunky Dory still selling, especially after a bombshell interview in Melody Maker where Bowie danced around and goaded interviewer Michael Watts with comments about his sexuality, Ziggy had to wait just a bit longer to land on Earth, even if Bowie was more than a few steps ahead of everyone else.

In the explosive interview with Melody Maker, Bowie teased what was to come: “I’m going to be huge,” he told Watts. “And it’s quite frightening in a way.”

“The whole thing with David was that he was never in today,” Scott says. “He was always in tomorrow. It was only three weeks after recording Hunky Dory that we recorded Ziggy Stardust. That leap from Hunky Dory to Ziggy occurred over three weeks.”

“Starman” was released in April 1972, though it didn’t enter the U.K. Top 40 until July, catapulted by a shocking (at least by early-1970s standards) TV performance by Bowie and the Spiders.

In the meantime, Bowie had laid the groundwork for both the Ziggy Stardust album and character, headlining 26 shows, recording three BBC radio sessions (also included on the box set), and producing “All The Young Dudes” for Mott The Hoople. All the while, he kept up a grueling schedule of interviews and photo shoots, including a three-day promotional trip to New York City, where Bowie saw Elvis Presley at Madison Square Garden.

“Tony DeFries, his manager, had come along and said, ‘Just create. I will take care of you, and you will just write without worry,’” MacCormack remembers. “And Angie, his wife at the time, was quite a big force as well. So he had this backing, and he had moved to Haddon Hall [his South London mansion], where he had space to rehearse, and the apartment was fantastic. All these things came together at once. But mostly, the freedom to create was a huge thing. That’s why he started to be more active, more productive. It all gushed out, because it had been there on shelves in his head somewhere.”

When Bowie returned from New York to London, he honed his inspiration, to shocking effect.

“I got most of the look together for Ziggy, and it was basically a Kubrick film A Clockwork Orange,” Bowie said years later. “The jumpsuits in that were just wonderful, and I liked the malicious, kind of malevolent quality of those four guys, although aspects of violence themselves didn’t turn me on particularly. So I wanted to put another spin on that. I picked out all these very florid, bright, quilted kinds of materials, and so that took the edge off the violent look of those suits, but still retained that kind of terrorist, ‘we’re ready for action’ kind of look. And the wrestling boots I think we had with the laces on, but I changed the color, made them greens and blues and stuff like that.”

About his backing band, Bowie added, “The Spiders played the part perfectly… Everybody was straight out of a cartoon.”

The Japanese Photographer Who Captured David Bowie’s Ethereal Beauty

While the inspiration for Ziggy himself has long been settled to be based on the English rocker Vince Taylor and the Texan musician The Legendary Stardust Cowboy, MacCormack insists rock ‘n’ roll itself was always the rocket fuel that inspired Bowie, right until the very end.

“The discovery of rock ‘n’ roll, which we were at the birth of, wasn’t like hearing a great album from a new artist,” MacCormack says. “This was an unknown life force that presented itself in the form of Little Richard.”

“Ziggy quickly became a concept, but also a way to make a bit of theater,” MacCormack adds. “And by then, he could write and produce at will.”

Bowie’s fifth studio album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, was released in June 1972 to near unanimous acclaim and instant commercial success.

“David had waited so long to do what he wanted to do,” MacCormack says. “So when Ziggy exploded, he was ready. It gave him an audience and, suddenly, he knew he was being heard and he was headed somewhere great. He was no longer trying to simply get his foot in the door. He was in.”

After eight long years in the wilderness, Bowie had conquered the music business and had within his grasp a future full of endless characters and experimentation—not to mention moments of global domination—that would last until his untimely death in 2016 and would, ultimately, be bigger than any one record ever could.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.